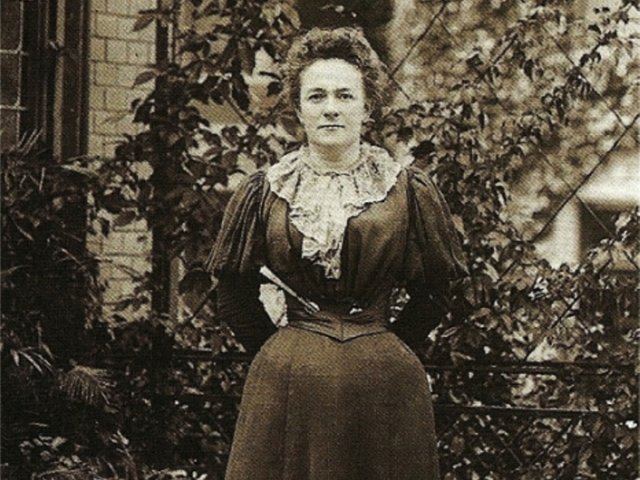

Feminist and communist: Clara Zetkin

Photo: Archive

After the murder of Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg in January 1919, it was Clara Zetkin who represented the continuity from the left wing in the pre-war SPD to the KPD, which emerged from the anti-war opposition and was founded at the turn of the year 1918/19. The pioneer of the proletarian women’s movement before the world war took the step to join the KPD with a certain hesitation. Despite all the substantive agreement with the founders of the KPD, she had long hoped to win over many people from the Independent Social Democratic Party (USPD), which was founded at the beginning of 1917, to the politics of the radical left. So she only took the step to join the new party in the spring of 1919.

The fact that the 61-year-old woman living in Stuttgart was in poor health may also have played a role. This meant that she was not available for the central party leadership; The party’s chairmanship was eventually taken over by Paul Levi. But of course she belonged to the extended leadership group whose word was heard. This also applied at the international level, where in the following years she was to represent the KPD at many meetings of the Communist International in Moscow and maintained contact with Lenin again and again. She also acted as a representative of the KPD and the International vis-à-vis other parties that were being formed.

It is not only her extensive journalism that bears witness to her numerous activities, especially in the Social Democratic women’s newspaper “Die Gleichheit”, which she ran since 1892 until the SPD party executive deprived her of the editor-in-chief during the World War. Numerous letters have also survived. They will be carefully edited in a multi-volume collection for the period from the beginning of the World War until her death in 1933.

In 2016, a first, 500-page volume, edited by Marga Voigt, was published covering the period from 1914 to 1918. Now a second is available: on the early days of the KPD from 1919 to 1923; Jörn Schütrumpf joined as editor. The Berlin historian has already overseen an extensive edition of Paul Levi’s works in recent years. Although he belonged to a different generation than Zetkin – he was 26 years younger than her – their paths had crossed again and again since the immediate pre-war period. Their political work was closely intertwined until 1922, only to then drift apart.

Schütrumpf titled his introduction “Under the Bolsheviks.” This is also the tenor that determines Zetkin’s letters to a wide variety of addressees. Problems are addressed that arise from the most contradictory “teething problems” of the young communist parties in various countries. On the one hand, they arose from attempts to imitate the Bolsheviks, who were successful in Russia, with their own revolution, regardless of whether comparable conditions existed or not. On the other hand, from the pressure that the victorious Bolsheviks put on the international workers’ movement so that they would no longer stand alone in a hostile capitalist environment.

In 1921, the KPD leadership was carried away by the infamous “March Action,” encouraged by emissaries from Moscow. Six months earlier, the KPD had become a mass organization through a merger with the left-wing USPD. Now there was a risk of gambling this away again. The resulting conflict within the KPD leadership as well as with the leadership of the Bolshevik Party is perhaps the most serious problem that emerges in this volume. Clara Zetkin was one of the harshest critics of this adventure. But unlike Levi, she was not prepared to break with the party. Ultimately, their priority was to preserve the unity of the party, especially in the face of state persecution. The obvious conflicts were masked by numerous compromises. This fatal tendency in Clara Zetkin’s behavior was to become even stronger as a result. The Bolshevik revolution, the only successful one, was too important to turn away from.

This volume of letters also deals with Rosa Luxemburg’s political legacy as well as the first political trial in Moscow against the former leadership of the Social Revolutionaries, as well as the events surrounding the failed “German October”, the KPD’s last attempt at revolution in the crisis year of Weimar democracy 1923. In the same year, Clara Zetkin analyzed the new manifestation of counter-revolution in the form of fascism in Italy. Many of their insights were then ignored by the leadership of the Communist International for political reasons. Of course, the letters also talk about private matters, the increasing deterioration of her health, worries about her sons and much more.

The volume is excellently edited, including profound explanations and notes on events and people mentioned in the letters, as well as a number of additional contemporary documents. It offers a rich treasure trove for readers interested in the early history of the KPD. At the same time, it makes you curious about the following volume, which traces the fatal consequences of Stalinism for the KPD and the Communist International.

Clara Zetkin. The letters 1914–1933. Vol. II: The Revolutionary Letters (1919–1923). Ed. Marga Voigt and Jörn Schütrumpf. Karl Dietz, 735 pages, born, €49.

Become a member of the nd.Genossenschaft!

Since January 1, 2022, the »nd« will be published as an independent left-wing newspaper owned by the staff and readers. Be there and support media diversity and visible left-wing positions as a cooperative member. Fill out the membership form now.

More information on www.dasnd.de/genossenschaft

sbobet link sbobet link sbobet sbobet