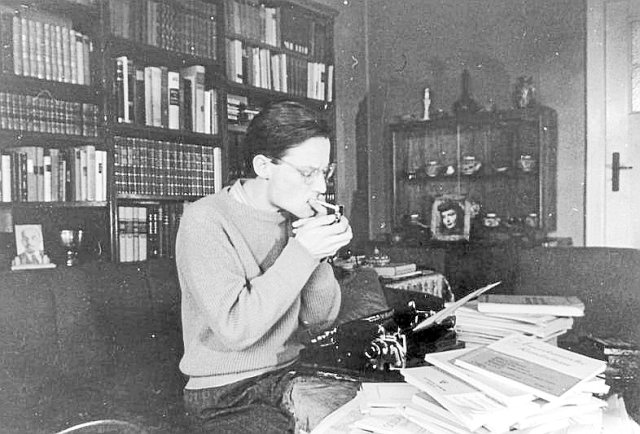

Wolfgang Harich at work in his apartment, around 1947

Photo: wikimedia/Treasury

He was to develop into one of the most dazzling personalities in the GDR on several levels – and where there is dazzling there is also a shadow. Wolfgang Harich, who was born 100 years ago on December 9th in what was then Königsberg, had and still has both: great thoughts and some far-fetched visions.

The young Wolfgang grew up in Neuruppin. Harich himself has hardly said anything about his childhood and youth, parents and family roots. It was previously known that mother and father came from educated middle-class families and worked in the newspaper industry. People knew the stages of his life and knew that Wolfgang Harich was closer to his loving mother than to his authoritarian father.

In the recently published 16th volume of the “Writings from the Estate of Wolfgang Harich” there is a new piece of the biographical puzzle: under the title “Neuruppiner Jugendjahre” the Harich editor Andreas Heyer published an autobiographical document that Harich wrote in 1975 together with his interlocutor Wibke Bruhns created. It is a fragment. In it, Harich describes the history of his ancestors in detail and raves about his years in Neuruppin – for him “the most important city in the world”, thanks to Fontane, Friedrich II and, above all, Schinkel’s architecture, which anticipated New York. The text ends in the early 1940s with reflections on the Second World War and descriptions of his juvenile love life.

The family was liberal-minded, they couldn’t do anything with communists, and even less so with fascists. But that didn’t help the 18-year-old against having to wear a Wehrmacht uniform and being sent to the Eastern Front. Harich didn’t last long there. He evaded military service twice; pretended to be sick, went into hiding and hid in Berlin during the last months of the war. Here he helped the communist resistance group “Ernst”, sometimes at breakneck speed.

After the end of the war, Harich became a young, dazzling superstar of the East Berlin art and intellectual scene: theater critic, philosophy lecturer at the Humboldt University, editor-in-chief of the “German Journal of Philosophy”, on an equal footing with the great minds of his time, with Becher, Bloch, Brecht and others especially Lukacs. Harich had contacts in the highest circles – and overestimated his political possibilities. He learned this the hard way at the end of 1956, when he was declared the ringleader of an opposition “Group Harich” and arrested. At the beginning of 1957, after a show trial, the verdict was given: ten years in prison. The communist dandy couldn’t fall much lower.

Now the shadow came: his health and psyche were ruined in prison, he was not allowed to do research, read or write until shortly before he left prison, a heart attack was not treated, and paranoia developed. And yet he remained a communist and decided to join the GDR after his release. His reputation was now tarnished because he had testified against former colleagues in the trial and while in prison, sometimes denouncing them. From then on they accused him of treason, without understanding his version of the story, according to which the Stasi had otherwise threatened him with death. His argument can be found in a previously unpublished manuscript from 1992. It appeared in the 15th volume of the estate series. This contains individual “writings on politics”, for example the “Memorandum” and the draft of the “Platform” from 1956.

After his release from prison, Harich was allowed to do research on Jean Paul and Ludwig Feuerbach in the GDR. He was not allowed to return to the university. This did not stop him from commenting on current issues of Marxism, be it with a criticism of the neo-anarchism of the Western ’68 or with the call for eco-communism without growth in 1975. The 15th volume also contains texts on these topics. It also contains letters and articles from the period between the fall of the Berlin Wall and Harich’s death in March 1995.

For much of this, the reader needs background knowledge of world events at the time and the left-wing debates of those years. On July 16, 1994, the disappointed left-wing patriot Harich wrote a letter to the editor of the anti-German “Junge Welt” editor Jürgen Elsässer, in which he complained about his general hatred of all Germans.

Harich was one of the first GDR intellectuals to campaign for reunification in 1989/90. He envisioned a neutral, disarmed state. He was bitterly disappointed when he joined on October 3, 1990. He saw the state-financed reappraisal of the GDR as victorious historiography, which he opposed with an “alternative study commission”. He rejected legal action against former SED, NVA or Stasi members.

After Harich’s death, a dispute broke out over his inheritance. Some of his students claimed the estate for themselves. However, his widow Anne prevented this. In a cloak-and-dagger operation, she moved the entire contents of Harich’s study to the social archives in Amsterdam. The documents lay there for 15 years until the political scientist Andreas Heyer visited the archive with the widow’s permission, put the papers in order and soon published them.

Harich’s 100th birthday coincides with the 10th anniversary of the first published volume of “Writings from the Estate”. It began with texts about Hegel; This was followed, among other things, by volumes on Kant, Herder, Jean Paul, Nicolai Hartmann, Lukács, Harich’s vehement criticism of Nietzsche, the ecological question, anarchy and culture. 20 books (including some partial volumes) have been published, each with an extensive introduction. Around 70 percent of the estate is therefore available in print and can be read by everyone, as editor Andreas Heyer recently said at an event organized by Hellen Panke and the Rosa-Luxemburg-Stiftung. And at the end of the series he shares Harich’s late wish: “You shouldn’t write about me, you should read me, then you’ll see what’s left of you.”

Wolfgang Harich: Writings on politics.

Vol. 15 of the writings from the estate.

Hg. v. Andreas Heyer. 743 S., geb., 89 €.

Wolfgang Harich: Neuruppin youth. Vol. 16 of the writings from the estate.

Hg. v. Andreas Heyer. 689 S., geb., 79 €.

#ndstays – Get active and order a promotional package

Regardless of whether it is pubs, cafés, festivals or other meeting places – we want to become more visible and reach everyone who values independent journalism with an attitude. We have put together a campaign package with stickers, flyers, posters and buttons that you can use to get active and support your newspaper.

To the promotional package