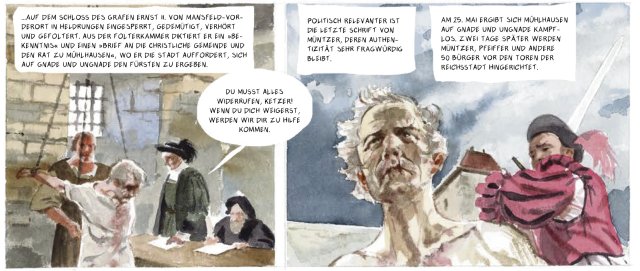

Thomas Müntzer leads troops under the rain bean flag. Below: Müntzer is tortured and executed. Both scenes from the graphic novel »1525. The uprising «.

Photo: Bahoe Books/Giulio Camagni (2)

Who still knows him, the man from the GDR five-mark note? Above all, it should be those who were socialized in the “Workers’ and Peasant state” before 1989- because this used Thomas Müntzer to stand in a traditional line with the farm survey in 1525. Keyword: Early bourgeois revolution. Müntzer’s life was closely linked to these events, which is commonly called German Peasant War. His execution after the lost battle of Frankenhausen formed zenith like fanal of the uprising movement. Müntzer became the controversy of the historians in East and West and the symbol, which itself refers to Latin American liberation theologians. One was considered to be awakening as a theologian, the other as a revolutionary with a rainbow flag. And he stands for an unresolved promise, because the questions of justice at the time are still up to date 500 years later.

The great unknown

“It was cloudy around him from the start,” the philosopher Ernst Bloch begins his Müntzer biography: “The young people almost grew up. Müntzer was the only son of little people to be born in Stolberg around 1490. He lost his father early on, his mother was treated badly, she was sought to remove the city as supposedly medium. The father is said to have ended a victim of count’s arbitrariness. So the boy already learned all the bitteries of shame and injustice. ”That sounds heartbreaking and as if Müntzer’s path would result from the circumstances of his childhood – alone, except for the place of birth in the Harz, nothing is prohibited.

Photo: Bahoe Books/Giulio Camagni

Müntzer’s exact date of birth is also unknown. The year 1489 is probably in 1489 when you recreate from your enrollment at Leipzig University. The social origin remains vague, the family will not have been completely impossible because he argued with the father. Further life stations in Müntzers are also fragmentary; Most documents date from the past five years of life. Even the name of his wife Ottilie was only known about detours – their traces and that of the two common children are blurred in 1525.

After studying theology, Müntzer works at various parishes and shared Luther’s church criticism. He was personally sent to Zwickau in 1520, where he developed an independent belief that differed radically from Wittenberg. Faith must be experienced by an inner process of suffering, humans suddenly understand the passion of Christ: So Müntzer’s conviction grew. There is no privileged access to God, it is open to everyone. He also saw the final court approaching – and thus the rule of Christ on earth: “The change in the world is sitting in front of the door”. As a result, Müntzer attacked old believers and the “gentle” doctors of the Reformation movement alike: they blocked people access to the true faith. For the cleaning of the church, he saw his guarantors in the farmers and citizens who rose in southern Germany.

Theologically justified resistance

In the spring of 1525, this movement reached its most violent expression and its greatest expansion. She caught the southwest to Alsace, raged in Upper Swabia, Franconia and Thuringia. The cause of the peasant uprising was a complex of deterioration in economic conditions and socio -economic positions, recurring physical rights and the prohibition of general use (forest, meadows etc.) as well as restrictions on freedom of movement and municipal autonomy. At a delegate meeting in Memmingen, the insurgents adopted the “twelve articles”, which, according to the English Magna Carta (1215), form the oldest demands for human and freedom rights. The insurgents expanded Luther’s idea of the freedom of Christian man, who was only free from God’s grace in faith, against his understanding of secular things. Müntzer also formulated a theologically justified right of resistance: if the rule does not protect the faithful, then they have to use self -help – be it with the sword.

In the spring of 1525, Müntzer worked in Mühlhausen, where insurgents had just argued the city regiment. He followed a call for help from the oppressed Franconian house and met an army of 8,000 partly well armed rebels. It had 14 guns, but no cavalry; The improvised farmers’ armament of forged ceilings and threshing flails is a myth. He was also never the “farmer leader”, to which he was later explained, but acted as a spiritus rector. The military leadership was in the hands of captains. The opponents – the landgrave of Hesse, Duke Georg of Saxony and the Braunschweig – united their armies of around 7,000 professional soldiers on May 15th. They fired the Wagenburg into which the insurgents had entrenched themselves. The first guns already panicked them. Many fled the city. Most did not survive the path and were made. The rural servants entered the city. In the end, 6000 deaths were opposed to six dead mercenaries on the prince’s side on the sides of the insurgents.

Nd.Diewoche – Our weekly newsletter

With our weekly newsletter . We’re Doing Look at the most important topics of the week and read them Highlights our Saturday edition on Friday. Get the free subscription here.

On May 27, 1525, Müntzer died through the sword at the gates of Mühlhausen, his chopped head is whispered. Previously, he had been confessed that contains the much -cited formula “Omnia Sunt Communia” (“Everything belongs to everyone”). This was probably accompanied by dangerous thoughts as a warning, and for later generations it was also a hope signal. Only one sentence is even more popular: “The people will be free, and God wants to be the Lord about it solely.” The second half of the GDR memorial stones often lacks.

A revolutionary project

The battle near Frankenhausen was not the last battle of insurgent farmers and citizens. But it set an end point. Around 1,000 castles and monasteries were destroyed in the year. The number of killed is estimated at up to 75,000. The Reichsacht was imposed on the survivors, they became legal and bird -free. The figures of the executed are between 2000 and 10,000 – 0.5 to 0.75 percent of the total population. Contrary to the popular idea of the “German Peasant War”, the description as a “revolution of the common man” comes closer to the events in 1525: They were not limited to German -speaking areas, there was no such nation state anyway. And not only farmers were involved, but many groups of the lower class.

Thomas Müntzer shared this request to change the order and justified it theologically. And he was sure which side is on. This project of a democratic theocracy or theocratic democracy was revolutionary. It used to show trains of ideology when Müntzer demask the Lutheran theology as an instrument of rule because it legitimizes the authorities. He should be right with the analysis: the Reformation developed into the princely reformation. It became a political means for the territorial lords to break away from Rome’s influence.

Contrary to the idea of the “German Peasant War”, the description as “revolution of the common man” comes closer to the events in 1525.

Müntzer’s thinking and acting did not remain ineffective, although it was intensively tried to let him fall. On the contrary, the discussion keeps him astonishingly alive as a figure. The Wittenberg part of all people, of all things, is of all part, which led to the formation of legends such as that of the bulletproof preacher – Müntzer would have browned with its invulnerability. Between the enthusiast, hitzkopf and revolutionary, the judgments fluctuate about him, which Heinrich Heine called one of the “most heroic and unhappy sons”. From the French Revolution in 1789, it began to see Müntzer in a different light. Because it had become tangible that the political order could be changed. Finally, he became the central figure of the German-German historian debate in the Cold War and was a figurehead of the GDR memory policy, which ironically made a preacher to her column saint. Müntzer’s theological ammunition to change the world even inspired Latin American liberation theology.

Who determines the interpretation?

Müntzer’s answers cannot be ours. But at least the questions that the allies asked the world are also currently 500 years later. In today’s discussions about the shortage of public space and goods, the privatization of waterworks and municipal electricity producers, access to living space and mobility, for example, the general question appears to be freely available as in the initiatives, intellectual resources. The claims for self-determination and co-determination are not yet fully compensated.

The last word about 1525 has not yet been spoken if the revolution recently described the revolution in junker words as “unrest” and “wild action”, sometimes high jazz on “Germany’s great popular uprising”. This shows a very large scope of interpretation that needs to be explored. The historian Arnulf Zitelmann warns: “Anyone who breaks the staff over Müntzer because they wanted to bring about a change in political conditions must be careful not to saw the branch on which he sits with his consent to democracy as the best state and company form of his time, one in the modern revolutions.” Müntzer and the revolution of the common man commemorated.

Tobias Prüwer: 1525. Thomas Müntzer and the revolution of the common man. Salier-Verlag, 168 pages, Br., € 22.

sbobet88 sbobet sbobet88 sbobet88