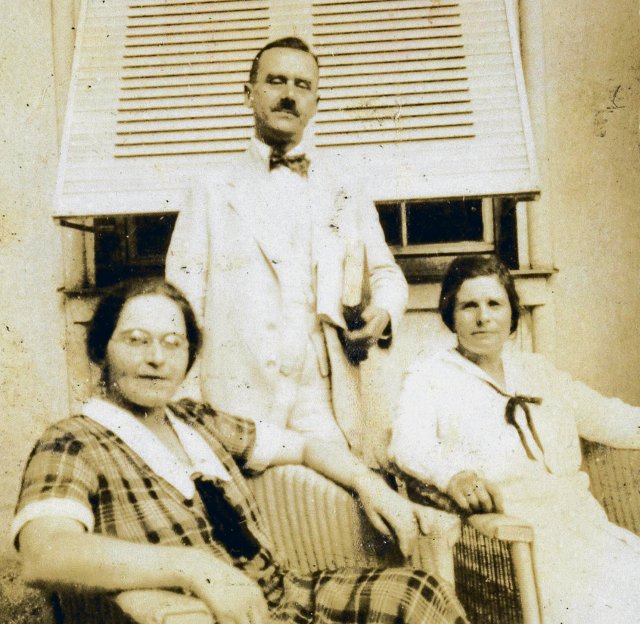

Thomas Man with his wife Katia and his admirer Ida Herz, 1925

Photo: ETH library Zurich / Thomas-Mann Archive / Photographer: Unknown

She saw him right away. Thomas Mann, who came from a reading in February 1924, drove to her surprise with the same tram from Fürth to Nuremberg. What a coincidence. She took all courage together, meandled him and imagined. She had read the “Buddenbrooks”, “Royal Highness” and with special fascination “Tonio Kröger”, and she raved about him. She really wanted to tell him that. A good 20 years later, he will remind you of meeting the 29-year-old Ida Herz in the »Doctor Faustus« with a light ridge. Then she is Meta Nackedey, “an outstanding, forever blushing, every moment in shame, which had fluttered through the full car” in “headless escape” to speak in a wayy. She even met Thomas Mann in 1922 (which he could not remember) and decided to take the opportunity to take the opportunity. In the next few days she bundled everything she could find through his readings and sent it to Munich. He thanked him for the “friendly letter” and invited her to visit him during a stay in the city, “preferably at 2 a.m.”.

“I ask you, a highly revered Dr., take me advantage of what it is for.”

Ida Herz to Thomas Mann

With this letter, one of the most extensive but also unknown correspondence began to correspond to Thomas Mann. He only ended with his death in August 1955. Ida Herz then tried again and again to publish the correspondence, but came across the family’s violent resistance. Katia Mann suggested a small selection. But nothing came of it either. Finally, Herz gave up resigned. And so it stayed with the view that Thomas Mann’s diaries offer. There she mostly haunts the book pages as an intrusive, annoying person. Sometimes she is the “hysterical old maiden”, then again “the unfortunate heart”. Most often the entry: “Unfortunately, the heart is tables”. The biographers, who knew that she was much more for the admired Thomas Mann than the dreaded table guest and that he appreciated her for good reasons, were happy to refer to his aversions and thus ensure a view that could hardly be slate, unjust, unjustwashing. For the first time after thorough research Friedhelm Kröll, in his book “The Archivist of the Magician”, published in 2001, vigorously contradicted, a strong plea for the woman who was previously thoroughly missed. It ended with the appeal to finally publish the correspondence. He was not heard. Only now, for the 150th birthday of Thomas Mann on June 6, did the letter collection appear at S. Fischer, edited with care and fantastically commented by Holger Pils. She brings all the traditional writing: 335 letters and postcards from Thomas, some also from Katia Mann and the 27 letters received by Ida Herz. Most of what this sent to the master to Switzerland and the USA, Thomas Mann threw an estimated 400 letters into the fire. He did that with another post. In this case, says Holger Pils, he apparently wanted to determine what should experience posterity in the event of a publication of the “complicated relationship”.

For Ida Herz, the Nuremberg Jew, born in 1894, this friendship was the miracle of her life, and whatever she thought and did had to do with him, Thomas Mann. “You give my cloudy life so much indelible, wonderful light through your friendship, through your work + your existence,” she said. “I would like to be able to be something for you now!” She had already written to him immediately after the Nazis took place when he just experienced the “complete overthrow” of his existence and suspected that he would not see his Munich house again after the lectures in Switzerland. “I ask you, a highly revered Dr., make a claim for what it is for. I want everything I can do for you! “

After many letters and some visits, they were familiar with each other. In the summer of 1925, Ida Herz had organized Thomas Mann’s library for weeks and gradually got to know the family. Now, in the spring of 1933, the many hours paid off on Poschingerstrasse. Katia Mann asked her because son Golo could no longer dare to save the working materials for the Joseph novels. It was known to Ida Herz later, a dangerous company. The villa, not yet confiscated by the Nazis, was monitored by the Gestapo. Heart bravely and reliably stowed heart, sometimes in the dark, writings and books in boxes and sent to a Basel deck address. Thanks to her care, nothing was lost. Mann was able to continue working on the novel, in the possession of the rich collection of the Joseph theme. Ida heart, however, was denounced, came into custody and again after six weeks through an amnesty, was soon blackened, fled in mid -September 1935 to Zurich and then to London, where she stayed until her death in February 1984.

Even in the years that did not make an encounter possible, she was brilliantly informed about the everyday life of the family, and that makes this band so significant: he fascinates the man’s living environment through his intensive looks. He, Thomas, told in mostly long letters from the new house in California (“We will never have lived as beautiful as in the” misery “), of writing hours and crises, about the surprising successes of” Joseph “in the USA, illnesses and visitors, children, companies and trips, plans and his political effort against Nazi Germany. And of course he continued to send newspaper reports, prints and books for the archive. She returned with letters and “good things”, many new releases and even with Easter eggs. Apart from moods, harmonious. That changed when Thomas Mann was back in Europe after the war. Heart believed that he had conquered a right. He feared closeness. Already in the United States, he had his rich patron Agnes E. Meyer, the “wonderful woman”, who gave him almost every wish from his lips, but also tried to cautiously steer him, described in the diary as hysterical and foolish person. It wasn’t better whenever she came to Zurich. She felt privileged by her willingness to help and the many friendship services. He, irritated by the loss of distance, was trying to be friendly. But he suffered. Once, in 1953, he lost, left with her alone, all mastery, “jumped up and went, crushing and disturbed,” out of the room, read a little and took a tablet to sleep. He knew that there was a lot together in these moments: his job, the dissatisfaction, perhaps the hairdryer, the house in Erlenbach am Zurichsee, which he did not like, plus the “always encountering floating fairy from girls”.

Heart was shocked when she read in the second diary band at the end of 1978, which he had written about her. For a while she ranked by the version, but her admiration for the author and work has remained. And she was able to comfort herself with the letter he sent to her in October 1954 for the 60th birthday. It was to be said that he wrote “that we have both participated for so many years and decades, one in the life of the other, with touching loyalty to my fate, my letter and activity, and I have to endure and change with great respect and sympathy; Because as you have led after the expulsion from Germany, kept and worked and passed life, it is so good and honorable that it is really worth respect and sympathy and friendship. «

Thomas Mann & Katia Mann: “Dear Miss Herz”. Exchange of letters with Ida Herz 1924 – 1955. Ed. By Holger Pils, S. Fischer, 799 pages, born, € 38.

judi bola online akun demo slot sbobet judi bola