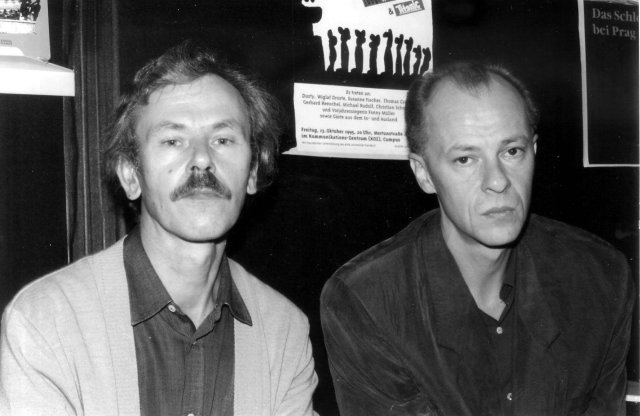

The social critic and his publisher: Wolfgang Pohrt and Klaus Bittermann in 1995 at the Frankfurt Book Fair

Photo: Edition Tiamat

“Society is when it hurts” is the first sentence in the last text that Wolfgang Pohrt wrote. In 2014, he has summed up his entire journalistic work since the mid -1970s. Only that the audience hurt its texts more than the society, in which it had somehow faced. Pohrt’s texts disturbed because he was bothered by the cosiness of opportunism. This made him as an analyst and essayist just as famous as it frustrated him in the long term because a politically serious change failed, because “capital is as simple and stable as the crocodile” as he stated in his penultimate book “Capitalism Forever”.

Almost all of his books came out in the Berlin Edition Tiamat, where-without any funding-a 13-volume edition of his writings appeared, which looks like the “blue volumes” by Marx and Engels. It began shortly before Pohr’s death 2018 and completed in 2023. Now there is also a “reader” of almost 500 pages that has a bulky title (“Wahn, ideology and loss of reality”), but presents a 1A introduction in Pohr’s work. A good addition to the Pohrt biography worth reading, which his publisher and the greatest fan Klaus Bittermann presented in 2022. Is that a little bit of pouring? But do you even know that? Read him! Or read it again, because like the apparently indestructible capitalist mode of production, most of his considerations remain timeless.

A puzzle pleasure

Pohrt was born in the Saxon province today 80 years ago and then moved to the Black Forest with his mother. He never got to know his father. In Freiburg he broke his Abitur, went to West Berlin and became auxiliary worker, caught up with his high school diploma at the evening school and began studying sociology because he had too bad grades for psychology. The subject bored him fatally, because “the lecturers shouted back from no banality”. He was used to feeling talking to Jerry-Cotton novels-until he discovered the “dialectic of the Enlightenment” by Horkheimer and Adorno, which he passed through like a thriller: “I understood everything and nothing.” He had to learn the foreign words in particular, but it was a pleasure, the book was “like the solution of an interesting puzzle” and then he studied. He moved to Frankfurt/Main, went to the SDS, worked for the revolution and did his doctorate on the theory of the value of use at Marx and then became a professional ideology critic because it did not go on with the “Socialist World Revolution”. Why not? That was still an interesting puzzle.

In 2012, he declared this project to be “finally” failed: “If you run your head against the wall, only the head breaks, not the wall.” His followers did not want to hear that as the left alternative milieu in the peace movement or at the Palestina solidarity 30 years earlier. At that time he was following the motto: “People tell me what they think and I tell them why this is wrong.” But these were not instructions like in the K groups or in the organic shops, that was a completely new “sound”, as Klaus Bittermann states in his afterword for reader.

If the “organized no”, as Johannes Agnoli expressed itself, is so difficult to make so difficult, then it was for Pohrt permanent scandal and challenge to attack the apologists of the existing – with aggressive, brilliantly formulated texts. “The main thing is negative no”, as the collapsing new buildings sang on their debut album “Collapse” at the time. So one of the anthologies with Pohrt texts could have been called that appeared with such titles such as “Salvation”, “End Station” or “Zeitgeist, Ghostszeit”.

Most punk

“Negative no”: As uncorruptible as the kitschy conformism of a notorious FRG-Link, dissecting after 1968, he was the most punk among the radical writers of the 80s, even if he was not interested in Biller, Droste, Goetz, Diederichsen or Drechsler for Pop at all. Just as Adorno was a pre-punk as a relentless social theorist and negative dialectic, at least by Greil Marcus in 1989 in »Lipstick Traces«. For Pohrt, Adorno was “the enemy of the state in the chair”, as one of his essays is called, a “stroke of luck” in a special position at the university, which was no longer achieved by his successors. Not even from Pohrt, the doctor of sociologist, who left the academic company disappointed in 1980 because he thought he could reach a larger audience as a freelance publicist.

In the beginning he also succeeded very well, because the left alternative audience cried out when he declared the peace movement to the “German -national revival movement” after their protagonists transformed the population into “our people”, which must survive at all costs. They were so proud of their mobilization successes against the new medium -range weapons and against the construction of nuclear power plants. The 68s had only dreamed of such large demos. For Pohrt, however, the “lie was denied by the necessary fateful connection of the individual in the national forced collective” the enlightening idea of humanity: to form an “association of free people”. The refinement of everyday life with better dishes, housing facilities and manners, i.e. what the left to left -liberal and later green milieu had actually enforced since 1968, was not an expression of successful emancipation in 1974, but “was only possible in real life”, which would only be possible in a different society. In contrast, he demanded that “to recognize the fatal need in the X -ray image of the little joys of everyday life, either tear down or fail the existing social conditions”.

Relief for Auschwitz

But what seems to be possible in this milieu is projection and pathos, for example the enthusiasm for the Palestinians in the Middle East conflict, driven by a longing for “relief for Auschwitz”, which Pohrt summarized in 1982: “The oppression and persecution of the Palestinians by Israel is observed and so passionately denounced because it is not supposed to prove: there is no difference between the German crimes”- the Jews and the crimes that other states commit, especially Israelis on Palestinians.

This perspective is still virulent when the Gaza disaster war of the right Netanyahu government according to the Hamas massacres on October 7 by many left is referred to as “genocide”. For Pohrt, however, it was clear: “At German extermination camps, and nowhere else, the term genocide finds its destination: as a planned, systematic, continuous murder of millions of people, with which no other purpose and no other intention combine than just that of annihilation.”

This was preceded by his preoccupation with the literature of Jewish concentration camps such as Primo Levi, Elie Wiesel and Hermann Langbein, who told how they felt guilty. All the more absurdly, Pohrt seemed to be articulated by the idea, which is still articulated by literary associations, over church days to the CDU and even further on the right that German society has “mastered” the Nazi extermination policy. Just as if “two instigated world wars (…) were the best starting conditions when it comes to first place among the world peace judges and world peace pencils”. With the slogan “never again war, never again Auschwitz”, Joschka Fischer was the first green foreign minister to justify the first German participation in war after 1945, against the Serbian residual Yugoslavia. This form of “coping” is also articulated in a “responsibility” towards Israel, which was always listed from left to right, that Pohrt accentuated in 1982: “The mass murder of the Jews is committed, Germany is said to be moral with praise and tadel so that the victim does not relapse.”

In the Middle East conflict, the Palestinians compared with a militant association of displaced people in the struggle for the plaice, but also regarded the Israelis as one, albeit with the better weapons. If it were the other way around, the Palestinians behaved similarly to the Israelis in 1982 in the Lebanon War, he believed: “You don’t want to be one of the persecuted and displaced persons,” was his resignative, negative punch line.

Resentment in moral business

Such considerations, as well as its distinction between anti -imperial and anti -Americanism (now completely leveled) or its amusement over home staff as “rebellion of the Heinzelmännchen”, caused displeasure in moral operation then as now. The texts in which you appear are the big punk hits of the Wolfgang Pohrt in the 1980s, which are gathered in this reader as on a best-of album.

After that, his texts become calmer, more accomplished and also scientific, his studies of the authoritarian character of the Germans after 1989/90 and the applicability of racket theory in politics and crimes have something of sophisticated concept albums that no longer worked with such strong effects. When the blogs opened on the Internet, he developed the self -interview into an adequate text form, but printed medial in the monthly magazine “Specifically” under the title “Pohrt replied”. This in turn recalled concerts in smaller clubs with an acoustic set. Towards the end of his career, he served ironic hymns on capitalism as ultimately victorious boss when he said that communism “expired like bathing water if you pull the plug”, which actually seemed a bit lost.

What should you do now without much view of political progress? You sit at home and read good books. So everything begins.

Wolfgang Pohrt: Wahn, ideology and loss of reality. Metamorphoses of German mass awareness. A reader. Edition Tiamat, 512 S. Br., 26 €.

Reading on Monday, 5.5. in Berlin, Volksbühne, 8 p.m.: Sophie Rois reads from his text for the 80th birthday of Pohrs

sbobet88 sbobet88 judi bola online judi bola online