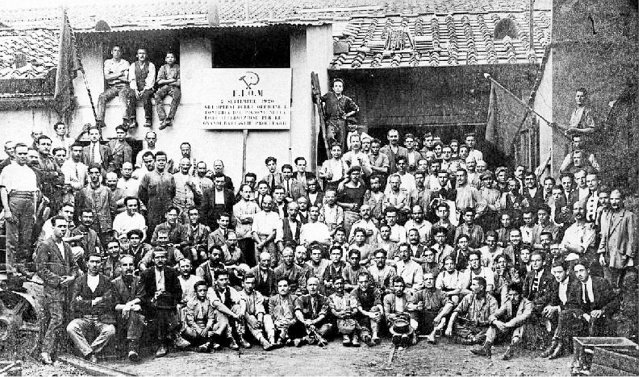

Revolutionary metal workers during the Biennio Rosso, the two Red years 1919/1920 in Turin, Italy. According to Mattei, the austerity was aimed against such self -authorization of the working class.

Photo: Solzialismus.Ch

Germany in 2025: 500 new super -rich, 3900 a total of a third of the entire assets in the Federal Republic, while real wages remain behind the inflation. The political response to falling consumption and export crisis follows the well -known pattern of debates about cuts in citizenship and social spending, while the wealth of the richest ten percent remains unaffected.

All of this could pave the way for an AfD government in 2029. When asked how exactly austerity measures and the rise of right forces are related, Clara E. Mattei found a disturbingly clear answer. Her book “The Order of Capital”, which was originally published in 2022, clearly shows “how economists invented austerity and prepared the way to fascism”.

Capitalism in the end

Mattei now presents a meticulously researched genealogy of savings ideology in German translation – and a warning of its political consequences. The Italian economist exposes a myth that has shaped economic policy for a century: that state savings in times of crisis are without alternative. Austerity does not serve economic reason, but the protection of capitalist power relationships. The shortening of social services – from education to unemployment benefit to infrastructure – follows a pattern that can be traced from Italy of the twenties to the Greece of the 2010 financial crisis. The consequences are poverty and unemployment for the many, during the wealth of the wealthy increases.

Matteis thesis about this context leads back to the origins of the austerity ideology after the First World War. At that time, the economy was not only in the crisis, but capitalism itself faltered. In Great Britain like Italy, the workers had been able to gain the decisive knowledge that the system could be changed. The state war economy had proven: While pre-war capitalism was still as a natural Laissez-Faire state, state interference with production showed the design of economic conditions.

The humanitarian and economic catastrophe of the World War and the subsequent poverty were no longer perceived as inevitable fate, but recognized as the consequences of capitalist organization. The end of capitalism seemed closer than ever. In 1921/22, the real wages reached historical highs in both countries, the demands for socialization of industrial branches became more and more louder, and the workers demonstrated by strikes that it could reverse the power relationship.

Austerity as a counter -revolution

In this explosive atmosphere – which matte has come to life through journalistic sources from a wide variety of political spectra, not least by the weekly newspaper “L’Ardine Nuovo” founded by Antonio Gramsci – the austerity was not accidental. She fell together with the biggest workers in the history of Great Britain and Italy and was invented as a political counter instrument because of these strikes.

The answer of the ruling classes was as elegant as it was cynical: it used austerity as a political instrument. But not politics or the governing alone were responsible for this – it was the economists who invented austerity. Based on archive material from the Banca d’Italia, the de’-Stefani archive, the Bank of England and the Churchill Archives Center, Mattei reconstructs how economists such as Ralph Hawtrey or Luigi Einaudi represented austerity policy as an alternative need.

The real goal of austerity was to discipline the workers and the stabilization of the class relationships.

The picture that results from the sources is sobering: the actual goal of austerity was the discipline of the workers and the stabilization of the class conditions under the guise of scientific rationality. Economic questions should be “depoliticized” and treated ideological – a fallacy, because behind the supposedly objective economic reason was the ideology of capital.

Mattei impressively shows which stereotype of the worker prevailed in the minds of this economist: general laziness and personal responsibility for economic misery due to unproductive work. These narratives sound terrifyingly familiar – they are reminiscent of discourses about Greece in the 2010s or about today’s debates about citizens’ papers in Germany.

The true face of austerity is relentlessly revealed in the historical sources: it was neither about combating inflation nor about budget stabilization, but about securing profits by restricting internal consumption and systematic wage pressure. In this way, it should be exported cheaply and quick profits could be made. Unemployment has been described several times as “necessary evil” in the documents – an instrument that disciplines the workers disciplined, to accept every wage and effectively prevent resistance.

Where there is capital

Matteis comparison between the Democratic Great Britain and Mussolinis Italy is particularly illuminating. If you wonder how these two political systems could be comparable in the 1920s, you will be surprised by the similarities and mutual inspiration. Both pursued the same austerity policy – only with different means.

The fundamental difference was only in the implementation: While Great Britain reduced the austerity measures with direct, authoritarian interventions by reforms, cuts and the restriction of strike rights for unions for unions to internal measures, Mussolini’s fascist politics. Austerity, according to Mattei, works in every political system as long as capitalism determines social order.

This knowledge gains additional explosiveness by looking at the present. Whatever national governments at the time, today, is taking over supranational institutions such as the International Monetary Fund or the European Central Bank. The role of depoliticizing the economy is evident in these forms of impersonal rule, which dictate the states through debt rules what their deficit can look like in order to maintain their creditworthiness. This means: Privatization of state infrastructure to reduce social spending and maintaining low wages in order to increase the profit margin at least at short notice. Mattei therefore aptly defines the freedom of the market as “freedom from the demands of the workers” in order to do the order of capital.

The winners of this policy are more obvious today than ever. During the Corona pandemic, billionaires increased their assets by 54 percent worldwide, while millions of people were worried about their existence and were also called for saving. A perfidious system that systematically uses crises for redistribution from the bottom up – and drives the wealth accumulation of the wealthy.

Certainly, Matteis Historical Analysis may seem narrowed when you consider that the economic situation only has played a role for Mussolini’s takeover or the current European shift to the right. But their core thesis remains captivating: As long as the “order of capital” determines social life, every economic crisis leads to the same supposed solution – saving at the expense of the weaker majority.

Man -made constraints

Matteis book represents an excellent scientific elaboration and at the same time serves as an urgent political warning, which means that the so -called austerity in reality means: unemployment, poverty, low wages and, last but not least, authoritarian threats democratic structures. It is a well -founded provocation at the right time, which reminds that there are solid ideologies behind the “objective” language of the economy.

Matteis Warning is reminiscent of Max Horkheimer Diktum from 1939: “But if you don’t want to talk about capitalism, you should also be silent about fascism.” At a time when right -wing movements see itself on the up of the up and austerity policy as an alternative, this historical lesson is of worrying topicality. In contrast, the insight that the austerity policy is a political decision helps with fateful consequences. Matteis meticulous reconstruction of its history shows that the supposedly inevitable is man -made – and therefore also changeable.

Clara E. Matti: The order of capital: How economists invented austerity and prepared the way to fascism. Brumaire, 586 p., Br., € 22.