On the way to the Mars Theater

Photo: IMAGO/ZUMA Wire

It is hard to understand that there are colleagues who sit down at their clinically clean desks and from there write texts full of life. The birth of the article from pure spirit. Other authors, including myself, can only be creative when they are surrounded by large quantities of paper. Unread books, torn newspapers, notes on a forgotten project from last year. Literally the entire environment is a talisman as well as a source of inspiration.

At my editorial desk I always have a reprint of the 922 editions of Karl Kraus’ “The Fackel” in eleven volumes. A twelfth volume contains an index and Kraus’ drama “The Last Days of Mankind”. It’s hard to imagine starting to write without knowing Kraus behind me.

His quip “It’s not enough not to have a thought: you have to be able to express it” should serve as a warning to all of us – and especially to those who dare to formulate a few comments on the occasion of the word master’s 150th birthday. Where do you even begin with this figure of the century? But not with the “torch”, these 20,000 pages of printed paper.

nd.DieWoche – our weekly newsletter

With our weekly newsletter nd.DieWoche look at the most important topics of the week and read them Highlights our Saturday edition on Friday. Get your free subscription here.

A lot has already been said. About Kraus and the Jews. Kraus and the women. Kraus and his favorite enemies. Kraus and Austria. Kraus and his disturbing silence. Kraus, the language critic. Kraus, the satirist. If you’re in danger of lifting yourself on an object, then you might as well try to do the impossible.

For example like this. There is the already mentioned drama “The Last Days of Mankind”, a piece that has not wrongly been repeatedly declared unplayable. A tragedy in five acts, framed by a prelude and epilogue, which captures human catastrophe in dialogues. Doesn’t that sound rather conventional? The impression is deceptive.

The “hundred scenes and hells” that Kraus mentions in a preliminary remark are only an expression of enormous deepness – there are far more scenes and each one is a hell. The playing time, if you were to hear the piece word for word, would exceed every evening on stage and would probably be more like a week-long procession. The roles cannot be counted, every scene has new faces. No ensemble in a German city theater employs anywhere near as many actors as would be required for a faithful implementation.

But why such a drama that fills hundreds and hundreds of pages, that knows dozens of locations, whose polyphony must remain a mystery to the viewer? Because when war comes threateningly close to us, it can hardly be explained dramatically. “The Last Days of Humanity” is less an analytical thesis than a linguistic depiction of a society affected by war. Kraus reacted with him to the First World War in the summers of 1915 to 1917.

Kraus himself tells us the most important thing there is to know about the text: His text, shimmering in endless dialects, is tied to wartime Vienna (and the other war-torn corners of Europe) – which doesn’t give the reader the right to read the whole thing “to be considered a local matter.” The tragic, general character quickly becomes apparent. And despite everything that seems drastically exaggerated here, we unfortunately have to assume that it is actually possible in times when there is war. “The most unlikely conversations that take place here have been spoken; “The most glaring inventions are quotations,” writes Kraus. And his contemporary reader Kurt Tucholsky also considers what was manifested in writing to be “terribly real.”

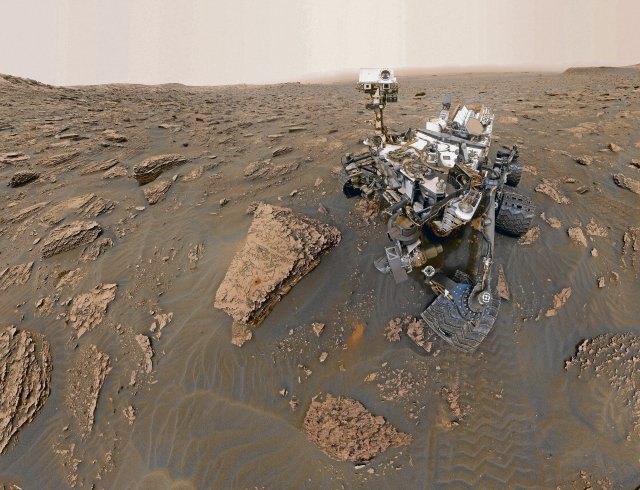

But the crucial thing is this: the performance of the drama is intended for a theater on Mars. “The last days” are, one may assume, not intended for this humanity. But Kraus lets us know: “Nevertheless, such a complete confession of guilt in belonging to this humanity must be welcome somewhere and of use at some point.” The Schaubühne perhaps not as a moral institution, but as a political institution that does not support the endlessly wrong life in the wrong one still glorified as a heroic act.

And there are as few heroes in “The Last Days of Mankind” as there are anti-heroes. They are the banal invention for a different kind of literature. But they all appear: the silent observers, the war enthusiasts, the undecided, the war profiteers, the eloquent journalist, the little man and the masters of the world. The fragments of a plot move from the hairdressing salon and the coffee house to the ministers’ offices and finally to the battlefield. But war is everywhere.

This completely non-local issue that we encounter in dialogues shows features of the current catastrophes. The newspaper sellers who persistently appear again and again at Kraus, praising their special editions about the horror in the world, are the human form of the impersonal live ticker of war events that descends on us today.

When you read how people are talking here – about the people in Eastern Europe, about your own national emotional life, the enthusiasm that it might now meet the right people – then you think of the tavern in Vienna in 1915. Just that? Reading from the comment columns of media companies only differs in superficial ways.

And anyone who doesn’t startle at the verses in the epilogue, “Let Hosanna ring out, let Hosanna ring out: / Bombs have fallen on the Mount of Olives!”, may no longer be able to be helped by human language.

Become a member of the nd.Genossenschaft!

Since January 1, 2022, the »nd« will be published as an independent left-wing newspaper owned by the staff and readers. Be there and support media diversity and visible left-wing positions as a cooperative member. Fill out the membership application now.

More information on www.dasnd.de/genossenschaft