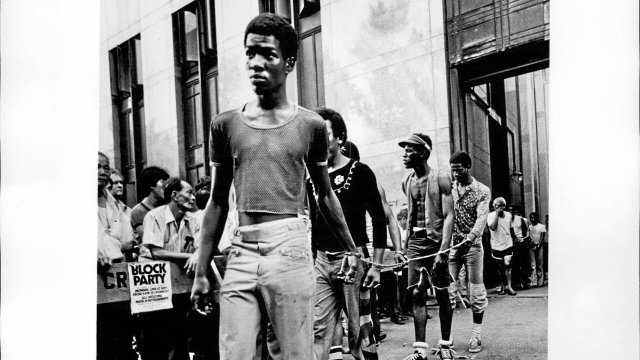

Racist class justice, July 14, 1977 in New York City: public arrest of black men accused of participating in looting.

Photo: imago/ZUMA/Keystone

Since the summer of 1977, a new threat was identified in almost every media, university, and campaign speech in the United States that would shape the country’s domestic political debates (and to some extent beyond) for about two decades: the new urban “underclass.” . The starting point for this discourse was the events that occurred during the one-day power outage in New York City on July 13th and 14th of the same year.

From the poor districts of the city, especially from Harlem and the southern Bronx, looting hordes had marched through the city, which had been in darkness since the late evening hours – and without, as in the race riots of the 1960s, any explicit demands for social or political ones participation would have been raised. When the lights came back on, the results were devastating: over 1,600 stores had been gutted, more than 1,000 fires had been set, almost 800 police officers, firefighters and passers-by were injured and four people had been murdered. The damage was estimated at the time to total $350 million, more than $1.7 billion in today’s money. New York’s mayor at the time, Abe Beame, then spoke of a “night of terror the likes of which the city had never experienced before.”

Propaganda against (black) poor

As a result, warnings about this supposedly new phenomenon took on an almost panicked tone. It all started with Time Magazine. From the August cover of the magazine, which opened with the hitherto virtually unknown term “underclass” – a term adopted by the Swedish economist Gunnar Myrdal – dark-looking figures looked out at the readers. All were African American and obviously poor. In the middle of the country’s large metropolises, the magazine’s editorial explained, there is currently a “large group of people who are more unruly, socially alien and more hostile than anyone could have imagined.”

nd.DieWoche – our weekly newsletter

With our weekly newsletter nd.DieWoche look at the most important topics of the week and read them Highlights our Saturday edition on Friday. Get your free subscription here.

The nature of this threat was already clear. This “minority within a minority,” it continued, produces “a disproportionate share of juvenile delinquents, school dropouts, drug addicts, and mothers living on welfare, as well as much of adult crime, family disruption, and urban decay and the need for social spending”. The urgent need for action that the author George Russell suggested to the public at the end of his article seemed to hardly need any explanation after this presentation.

It was a good thing that the concepts for a new neoliberal poverty policy were already in the drawer. In contrast to the “war on poverty” that Lyndon B. Johnson’s government declared in the 1960s, albeit with limited success, conservative foundations and think tanks had been working feverishly since the beginning of the new decade to bring about a paradigmatic change. Instead of expanding social spending, the Ford Foundation and the Manpower Development Research Corporation (MDRC), which was founded specifically for this purpose in 1974, called for strengthening the work ethic and initiative of the poor population, while for tactical reasons “avoiding direct confrontation with the racial question.” , as stated in the MDRC’s concept for developing state-funded job training for the long-term unemployed. The supposedly ethnically neutral term “underclass” proved to be an ideal basis for the broad campaign against the new poor that began in 1977.

Driven by hundreds of newspaper articles, but also by the eroding violent crime in the country’s cities, this discourse broke out publicly. The strength of this increasing hegemony can be seen in the fact that even a politician like Edward Kennedy, the standard-bearer of the progressive wing of the Democrats, adopted this view. At the convention of the civil rights organization National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) in 1978, he marked the “insidious growth of the underclass” as the “great, unspoken problem of today’s America.” And the demands to combat this threat were always the same as those already formulated in Time Magazine and the writings of the Ford Foundation: reducing social spending, performance bonuses in public education, tightening police measures, expanding courts and prisons, and subsidizing low-paying jobs in the private sector.

In the 1980s in particular, the new US government under Ronald Reagan set about implementing these suggestions politically, albeit initially cautiously. Above all, the New York journalist Ken Auletta’s 1982 bestseller “The Underclass,” in which he denounced the behavior of those left behind as “abnormal” and thus portrayed any pity for them as downright dangerous for public order, supported these attacks. The French sociologist Loïc Wacquant writes in his recently published study on the “invention of the ‘underclass'” about the importance of this new view of the poor, which can hardly be underestimated: Auletta’s book “popularized the word ‘underclass’ among the educated public and among political personnel and quickly established itself as a central reference, used by other journalists as well as academics and thinkers alike as evidence of the group’s existence.

From “Welfare” to “Workfare”

It is the great achievement of Wacquant, who teaches at Berkeley, to have subjected this hitherto little-noticed history of the neoliberal turn in US social policy to an in-depth discourse-analytical presentation. Starting from the paradigm shift in the mid-1970s, he traces the foundations and institutes now endowed with hundreds of millions of dollars and their ideological triumph. The Bourdieu student and star of the theory scene can start from his various studies on ghettos, prison systems and urban development in the USA, which once took him to the boxing clubs in the Chicago ghettos for research, where he had trained for years.

Wacquant makes it clear that the “breathtaking triumph” of neoliberalism – in the USA, above all, the transition from the system of welfare to that of workfare and prisonfare – could be achieved without the stigmatization of the poor, always associated with African Americans, as lacking work, performance and… “Underclass” unwilling to integrate could hardly have happened so smoothly. And he points out that this term was never an analytical category, but rather a very effective weapon for “crypto-racial moral” enemy identification, which succeeded in arousing disgust and fear, especially among the US middle class generate; A discourse, by the way, that was only too readily used in Germany when preparing for Agenda 2010.

The sudden disappearance of the “underclass” from public reporting and university seminars also supports this thesis: with the welfare reform implemented by the Clinton administration in 1996 in collaboration with the Republican congressional majority, which required transfer recipients to accept work in the low-wage sector , the neoliberal propagandists slowly lost interest in the repeated stories of the “racialized folk devils” (Wacquant) from the “underclass.” The term had done its job.

Economic fundamentals

Wacquant in no way denies the real changes that have taken place since the deep crises in the US economy and the de-industrialization that took place since the beginning of the 1970s, which in fact led to a spiral of impoverishment, lack of prospects, new racism and violence in US cities that was at times almost impossible to control led. “The emergence of the post-industrial precariat, increasing immigration and housing shortages, the punishment of poverty and the death of the ghetto” through the exodus of the emerging black middle class have led to an “erosion of social citizenship in the lower regions of social and physical space.” , which would have made explosions like the one during the New York blackout virtually unavoidable.

Anyone who wants to learn more about the macroeconomic processes of the time will have to pick up other literature, such as Robert Brenner’s “The Economics of Global Turbulence.” Without Wacquant’s groundbreaking discourse analysis, the conservative rollback in the USA since the late 1970s will be difficult to understand.

Loïc Wacquant: The invention of the “underclass”. A study on the politics of knowledge. A.d. English v. Christian Frings. Dietz-Verlag, 215 pages, br., 25 €.

Become a member of the nd.Genossenschaft!

Since January 1, 2022, the »nd« will be published as an independent left-wing newspaper owned by the staff and readers. Be there and support media diversity and visible left-wing positions as a cooperative member. Fill out the membership form now.

More information on www.dasnd.de/genossenschaft

sbobet link sbobet link sbobet judi bola online