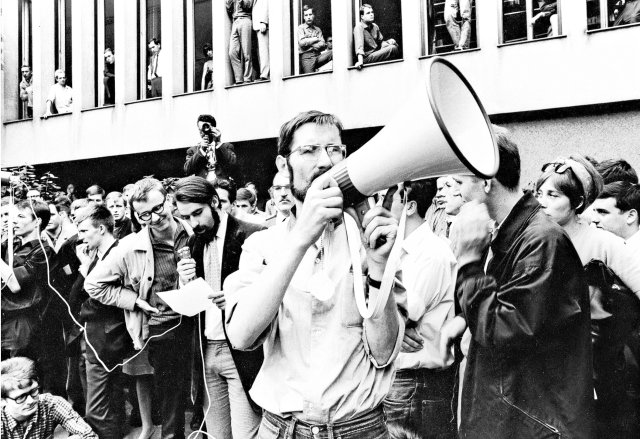

Slogans from the time of the student revolt, many of which are still relevant today

Photo: Revolte/ Bernard Larsson

Bernard Larsson is a photographer, he studied photo design in Munich and became an assistant at the fashion magazine “Vogue” in Paris. At the age of 22 he moved to Berlin; the wall had just been built. With his Swedish passport he can see East and West Berlin. At the height of the student movement, between 1966 and 1968, Larsson was back in Berlin, this time on behalf of “Stern”. Curiosity drives him, the time is pumped up and exciting, he wants to be there.

On June 2, 1967, in a dark garage courtyard in Charlottenburg, he took what has now become an iconographic photograph of the dying student Benno Ohnesorg. Shot in the back of the head, Friday evening after half past eight. The perpetrator of the weapon, police officer Karl-Heinz Kurras, is, as it later turns out, an employee of the state security department. It will never be properly clarified whether and what role the Stasi actually played in this context. Kurras takes the secret to his grave in December 2014.

After this unpunished execution of a defenseless student on the street, the world is a different place. This fatal shot radicalized the student movement, and some later took up armed struggle in the “Red Army Faction” (RAF).

“When we lost our innocence,” is the title of the text by journalist and politician Luc Joachimsen in the book. An “outbreak of almost warlike violence against astonished civilians,” she notes in one of Larsson’s photos. The Shah’s Persian cheering squad storms with wooden slats against unarmed demonstrators, German police stand by and do not intervene.

“Is there no one here who can help?” shouts Friederike Hausmann, bending over the dying Benno Ohnesorg. Behind the exhaust of a VW Beetle lies the bleeding student, a document of contemporary history, a staged scene, frozen in this moment.

Bernard Larsson will be 85 years old next May. The elderly photographer came to Berlin from Munich specifically to present his book with around 100 black and white prints at the Charlottenburg Gallery. He always saw his photography as political, he says; he wanted to “tell something, move something,” and draw the viewer into his photographs. The key data is given quickly. December 1966: Vietnam demonstration; March 1967: Demonstration against the emergency laws; April 1967: Anti-Springer Press demonstration; June 1967: Demonstration against the Shah’s visit; June 2, 1967: Execution of Benno Ohnesorg.

The book contains texts by Franz Josef Degenhardt (“Don’t play with the dirty children”) and Dieter Süverkrüp (“Song of Death”), as well as essays by contemporary witnesses such as Ulla Hahn, Beate Klarsfeld and Alice Schwarzer. Gregor Gysi also has his say. Looking back and at Larsson’s photographs, he warns against draconian measures by the state and pleads for the causes of protests on the streets to be investigated and eliminated, because: “contrary to all will to insist, social development never comes to pass.” End and (need) the commitment of people again and again.”

Konstantin Wecker sees the photographer Bernard Larsson as “a partisan chronicler of the protests against the emergency laws, the Nazi stuff at the universities and against the criminal war of the USA against Vietnam, etc. from 1967 onwards.” And at the same time “a documentarian of the subcultural awakening of the 1960s, for example in his touching photos of Jimi Hendrix.”

Unfortunately, the book does not contain a biographical interview with Bernard Larsson or an enlightening background text from him. In the exhibition he doesn’t appear to be a great speaker either. As a contemporary witness, Larsson himself remains largely hidden behind his photographs.

Photographs by the chronicler from East and West Berlin, taken between 1961 and 1964, could recently be admired in Berlin’s Berinson Gallery. These are also documents of the time. Border facilities in Hohen-Neuendorf, West Berlin: A house has been walled up because it is now in the border strip. A slogan in large letters: “All of Germany must become the people’s property!” An organ grinder in front of the Friedrichstrasse train station, little GDR flags adorn his music chest. There are also some portraits: Helene Weigel in front of her apartment in Hof Chausseestraße 125; Wolf Biermann in his apartment at Chausseestraße 131 in 1966; Anna Seghers, Stefan Heym, Peter Handke.

All of these photos of contemporary history in elegant black and white are a treasure trove of first class. Bernard Larsson himself sees his eloquent work modestly and at the same time self-confidently as “source material”.

Bernard Larsson: Revolt. The ’68 movement in images and texts from contemporary witnesses. Goya-Verlag, 192 pages, hardcover, €35.

The occupied Free University of Berlin

Photo: Revolte/ Bernard Larsson

Become a member of the nd.Genossenschaft!

Since January 1, 2022, the »nd« will be published as an independent left-wing newspaper owned by the staff and readers. Be there and support media diversity and visible left-wing positions as a cooperative member. Fill out the membership form now.

More information on www.dasnd.de/genossenschaft