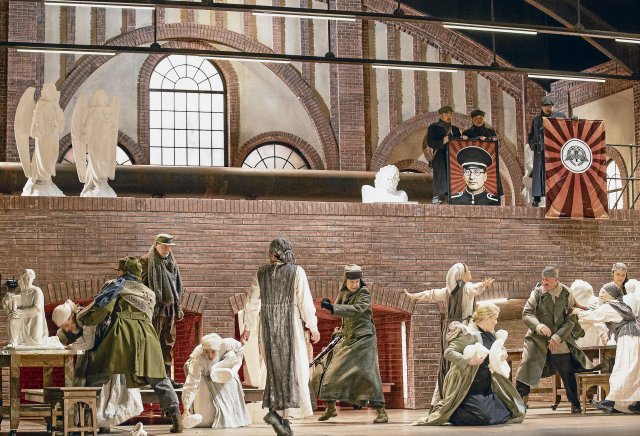

You too, worker Norma? Vasily Barkhatov stages Bellini at the State Opera under the Linden.

Photo: Bernd Uhlig

All of Gaul is occupied by the Romans. All of Gaul? Yes, all of Gaul! At least in Vincenzo Bellini’s opera »Norma«, the Tragedia Lirica in two files. Only the Gallic druid high priest Norma gives hope for an uprising suppressed by the Romans. But Norma is tangled – with her lover Pollione, the Roman governor, maintains her, vows or not, a love relationship from which two children come from.

When Pollione turns away from her and a new loved one, Adalgisa, a novice also with chastity vows, and Norma learns about it, she threatens to kill the children together, and for personal reasons, and fetched the oppressed people to the longed-for revolt against the occupiers. But finally she reveals herself and her betrayal and ends at the stake, including the newly from love for her Pollione Proconsul.

In his “Norma” staging at the Berlin State Opera Unter den Linden, a co-production with the music theater at Vienna, which is also supposed to hike to New York Met, Vasily Barkhatov converted the Roman occupation of Gaul into a political system change about 100 years ago. Norma is a foreman here (which you never see work) in a dark overall in a ceramic factory and lives in the connected worker dormitory and her two children, who tries to hide from the public.

This updated basic constellation offers the opportunity for new questions, but also leads to a number of discrepancies and constellations that contradict any logic. For example, why should the foreman and another worker of a factory in the 20th century have stored chastity vows? In the original, this is immediately understood, as a priestess, Norma must not entertain love relationships and even get no children. But as a worker?

Barkhatov saves himself in the assertion that Norma is the old -fashioned representative of an archaic religion that fails due to modern reality. On the one hand, it represents religious and, to a certain extent, ideological values, on the other hand, it does not adhere to the self -established rules and power of society, which is probably long more modern and enlightened, not only something, but lies her fellow human beings as well as her ex and his new loved one. Barkhatov develops this basic conflict to the core of his “Norma”: her lie becomes a big problem where it ultimately fails.

During the overture we see the ceramic factory in which religious sculptures are made. Then soldiers and other representatives of a new power storm in and destroy the Christian-religious statues. The first act begins, ten years later: in the factory, only busts of the new ruler are now made; For this purpose, a AI merged the heads of different dictators of the 20th century into a total authoritarian fantasy figure, the face of which is reminiscent of a mixture of Himmler and the Strelnikow from the Doctor Schiwago adaptation.

Nd.Diewoche – Our weekly newsletter

With our weekly newsletter Organization Look at the most important topics of the week and read them Highlights our Saturday edition on Friday. Get the free subscription here.

The mood in the factory is pressed in a brass. Norma’s father sometimes fits the watchers, but then withdraws immediately. One does not have the feeling that the workers are looking forward to a departure signal, even a blow to the dictatorship. Everyone seems to wait for Norma. Why actually? Because she can recognize anything from a few fragments of a religious plastic destroyed ten years ago? If she were the Gallic seer, it would make sense; In the idea of a foreman in a factory, on the other hand, one can expect tangible, instead of any incarnate fantasies.

In the first act, the famous “Casta Diva” aria can be heard, “Keusche goddess” so, “which you remember these holy old trees (uhem, one last time it was reminded: we are in a ceramic factory?). Rachel Willis-Sørensen, of course, cannot measure herself with Maria Callas in her rolling debut as a Norma, who dominated this game between 1948 and 1965 almost imperial and in any case unique. But in particular in this aria, certain excessive demands should be noted: their interpretation of the not only for this work, but for the standing, the meaning of the singing in the opera in the opera at all is not a magical summon that is completely the “long, long, long melodies” (Verdi about Bellini’s “Norma”). Rachel Willis-Sørensen’s trouble to take the heights “soft” and without forced permanent vibrato, generally have little to breathe and thus magically sound like Bellini’s lengths.

The other scenes, but above all the duette, terzette and the scenes with the choir, are much more to her; And it is precisely the conclusion that after a violent soul steam, she blames her fault of the Malaise with a simple “Son Io” (“I am”) on a simple C major chord, is a moment that moves in its simplicity.

But first Norma has to appease workers to vagem turmoil. “The days of your bloody revenge have not yet appeared,” she sings, “the Roman throwing floors are still far too powerful for the Gallic Beil.” No potion ,here. Again and again it is about the right moment of striking. Franz Josef Degenhardt described such moments in his ballad by the farmer leader Joß Fritz, a “legend of the right time”: “Don’t let the red taps flutter before the hawk screams”.

Barkhatov’s Norma, however, does not have a clever, real political reasons for her hesitation. She knows that her lie, her fraud, would be exposed if there was a revolt against the system and therefore against Pollione, the father of her children and leading representatives of the authorities. Only when Norma realizes that Pollione has agreed with her colleague Adalgisa and wants to take them to Rome: She changes her attitude: Now she wants to cruel revenge for his betrayal, now she is considering killing her children in order to prepare her ex-lover the greatest possible pain, and now she suddenly ranks her colleagues to venture the uprising-out of personal calculation, not out of social responsibility.

The special thing about Bellini’s opera and also on Barkhatov’s staging is that Norma is not getting crazy. In the romantic music theater that would be the obvious “solution”, but not with Bellini. Wagner, who appreciated Bellini and in particular his “Norma” over the dimensions, understood the piece as “Soul painting of this wild seer, who we see through all phases of passion until the heroic death resigned”. And that is exactly what we are experiencing: the central scene in which Norma of Polliones experiences techtelmechtel with Adalgisa (and this hears that pollione with Norma has two children – it is one for all three tremendous detection), is a highlight of opera and staging. The three sing their very different texts at the same time, “like shocking, and the tone of the music changes every few bars” (Barkhatov). Elmina Hasan, who masters the mezzo-soprano game of the Adalgisa vocal vocal in all shades, is not insignificant for the success of this heart-moving Terzett.

Ultimately, it becomes credible why Norma reveals herself, admits her lie and realizes that she can show itself weakly, without provoking strength, as it says at Marcuse. The Celli play con dolore, so “with pain”. And when Norma sits next to Pollione, the head of which she just pulled out of the noose (his hands, however, lets her tied up), lights a cigarette and shares her with her ex, there is no great drama, rather resignation and melancholy.

At Bellini, all of this does not take place in exalted turns of the acting figures, but in the music, which he adapts very precisely to the respective sense of the word (unlike that of Metternich and the conservative claqueurs of the after-Beethoven era). Here singing is a “category postproof geniality” (Ulrich Schreiber). Harmony and rhythm are rather banal, we know that from rock music or techno. But the balancing of movement and tranquility in Bellini’s music is “just terrific” (again Wagner). And the eroding sound waves, which Bellini uses in the late E minor Arioso, predict the final of Wagner’s “Tristan and Isolde”.

The Belcanto fans among the neokons are not used simply at Bellini, and the Belcanto controllers have to be heard by Wagner as early as 1837 that they only want to “hear the ordinary Italian sounding sound in Bellini’s” Norma “. But there is more in this opera. Conductor Francesco Lanzillotta understands her in the successor of Cherubini and Beethoven and as a predecessor of Wagner; Unfortunately, he cannot really make the Staatskapelle Berlin glow.

In the end, Barkhatov does without the couple’s “love death”: the flames in the fuel stove of the factory can already be seen, but Pollione tears back Norma against her will. The relationship has failed, but life continues. Will there still be an uprising?

Next performances: April 16, 21 and April 26th

www.staatsoper-berlin.de

sbobet88 sbobet link sbobet sbobet