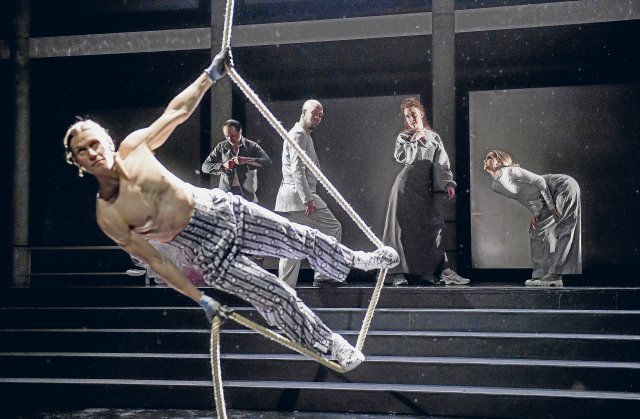

Military, musician, acrobat: the drum major (Philipp Grimm) is impressive.

Photo: Sebastian Hoppe

A relationship dispute ended bloodily. In an act of jealousy, Franz W. murdered his unfaithful partner after she allegedly had an affair with a drum major. The father of their child was driven into family tragedy by considerable social and psychological pressure.

In this jargon, the events in Georg Büchner’s social drama could be exploited on the front page of the tabloids. Woyzeck’s murder of Marie would then be another violent act of partner violence among many. According to the Federal Ministry for Family, Senior Citizens, Women and Youth, 133 women and 19 men were killed by their partners or ex-partners last year. What remains invisible in these statistics is that transfeminine people whose official gender record is male are listed as men.

Woyzeck, who is made a test subject by the doctor and exploited by the captain, loses his mind because the circumstances leave him no choice. From today’s perspective, this sounds like an escape by murderous or aggressive men, as Kim Posster outlines in his critique of critical masculinity. “Violent hatred is only understood as a bad ‘consequence’ of injured needs and feelings and not as the driving force behind this structure of desire and emotionality itself,” it says in “Masculinity Betrayed!”

The theater director and actress Lily Sykes knows about this tendency to apologize. In her production at the Dresden State Theater she shows the moments in which the soldier Woyzeck sacrifices himself for his wife and child, but actually abandons them. Nihan Kirmanoğlu carries the evening with her strong presence as Marie, while the rushed Marin Blülle only brings the well-known trait of the sufferer from the often played role of Woyzeck.

“How would you kill me?” Marie asks the lovestruck Woyzeck in the first scene. They begin to roll tenderly on a foil, bites are hinted at and fake blood sprays onto the other person. The self-confident woman seems to have the upper hand in the game until she lies on the floor with her sweater stained red. Wrapped in the plastic wrap, her legs no longer twitch. The consensual scuffle turns into male violence and gives a foretaste of the claims that both Woyzeck and the drum major have on Marie’s body.

Alone with the child – the driven Woyzeck hardly looks at the son when he is at home – she feels tied to the house and hopes for freedom from the romance with the drum major. With a steeled upper body, Philipp Grimm dangles from a thick rope in acrobatic figures and flexes his muscles. “He stands on his feet like a lion,” Marie admires the handsome guy. She tries to attract him on her own terms, but this man also ignores the rules of the game. The leader of the marching band presses the woman against him and takes the caresses that he supposedly deserves. Even if the higher-paid corps commander offers Marie more security than poor Woyzeck, she knows that a new relationship of violence awaits her. Sweating and bare-chested, the men clash as they dance or compete for the woman as a trophy.

Woyzeck also becomes an object in the social structure. The captain, played by Sven Hönig, fluctuating between melancholy and hysteria, gropes the soldier who is supposed to shave him, and Ursula Hobmair, in the role of the calculating doctor, humiliates her patient by looking into his underpants. Just as Marie’s body becomes an available object, the superiors claim availability over Woyzeck’s body and soul. While he reflects on how limited his existence is and how limited his ability to act in society, those in higher positions are only interested in his work ability. Büchner was “perhaps the revolutionary of the time who placed the economic liberation of the masses at the ‘center’ of his revolutionary activity,” said Georg Lukács in his essay about the realist.

In his piece, which remains in fragments, Büchner deals with the real criminal case of the murderer Johann Christian Woyzeck, who stabbed his wife out of jealousy and was executed for it. The psychotic man pleaded insanity. Büchner derives the antihero’s crumbling language and paranoia from the consuming conditions of his life. In the production, the voices of his tormentors drive the trampled man to commit an “act of jealousy.” Opportunities to pause, spend a moment with Marie, listen to her and take her needs seriously as an overwhelmed single parent rarely appear.

Happy moments such as a visit to the fair with the little family or the song about the two royal children, which is performed live by musician Jan Schöwer about the love of the two protagonists, fall like the big red cloth that briefly hangs over the stage inflates, quickly collapses again. But these scenes are the key to tearing Woyzeck’s actions out of social determinism; to allow the insight that he wanted this violence that way – even lustfully approved of it, as becomes visible in the blood-soaked opening scene.

The strong female lead distances the audience from seeing the murder as a necessary step and excusing the act. At the end, a dance of pictograms projected onto metal plates comments on the story in its own way: love hearts – a fetus in the womb – a woman with a child on the playground – a man on the way to work. In fast forward, the gendered paths in life pass before our eyes. Then only the dagger, the murder weapon, flashes. Violence opens and closes the evening.

Next performances: December 25th, January 17th 30.1., 27.3.

#ndstays – Get active and order a promotional package

Regardless of whether it is pubs, cafés, festivals or other meeting places – we want to become more visible and reach everyone who values independent journalism with an attitude. We have put together a campaign package with stickers, flyers, posters and buttons that you can use to get active and support your newspaper.

To the promotional package