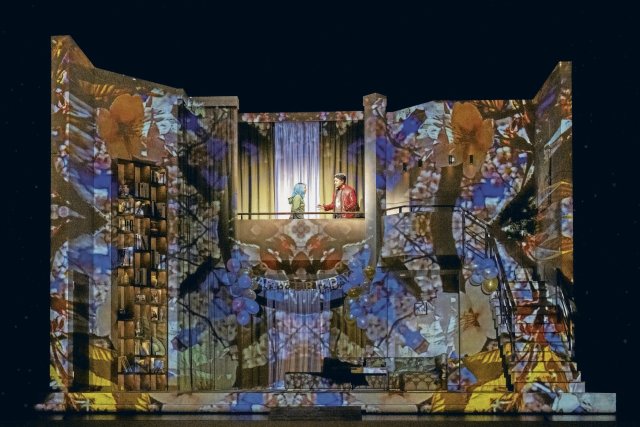

No nightingale to be seen. Not a lark either. Just the view into Julia’s room in the train station pub atmosphere.

Photo: Monika Rittershaus

Even those who have little knowledge of Shakespeare’s drama know Romeo and Juliet. A young man and a young woman from feuding families: the lovers par excellence – and a foreseeable tragic end saves the hassle of everyday life. So love can remain absolute.

Musicologist Elisabeth Stricher counts 38 Romeo and Juliet operas since the late 18th century in the State Opera’s program booklet; The material obviously invites you to set it to music. One of the most performed versions, alongside the symphonic poem by Pyotr Tchaikovsky and the ballet by Sergei Prokofiev, is the opera by Charles Gounod. The plot is cleverly concentrated on the most emotionally effective scenes, and the two title roles in particular are rewarding roles.

So that Roméo and Juliette have four love duets, even the ending is rewritten. In Shakespeare, Julia wants to avoid a forced marriage and takes a potion that puts her into a state of apparent death. Romeo thinks she is really dead and kills himself; Julia wakes up, sees her lover’s corpse and stabs herself. At the opera, however, Juliette comes to in time to sing a detailed farewell to the dying Roméo.

This all happens with a certain amount of discretion. In Gounod’s work, as in Wagner’s recently created musical drama “Tristan and Isolde,” the focus is on a pair of lovers who are moving toward death. But where Wagner used completely new means to achieve an intensity previously unknown on the opera stage, Gounod aimed for the approval of the audience, which he found immediately. The feelings of the young people who rebelled against their families to the death remained domesticated, at least always conveyable to all the parents who filled the auditoriums.

nd.DieWoche – our weekly newsletter

With our weekly newsletter nd.DailyWords look at the most important topics of the week and read them Highlights our Saturday edition on Friday. Get your free subscription here.

A development from formulaic music at the beginning of the work to the subjective at its end is only hinted at. To ears accustomed to bolder and more sophisticated harmonies, this sounds like a release controlled by reason; But reason doesn’t have to be the worst thing.

Director Mariame Clément has enough ideas, but are they any good? The hackneyed play-within-a-play concept that determines the prologue and a section shortly before the end is of no cognitive value: the choir sits on the stage as an audience and reflects the real audience. At first it seems more interesting to take up the discussion about classism.

In fact, Gounod’s opera shows a certain imbalance due to necessary cuts in the drama. Juliette’s family, the Capulets, actually appears as a family group, while Roméo’s Montaigus only appears as an unattached group of men. In Clément’s case, this becomes a conflict between top and bottom. But this doesn’t work.

The confrontation between the Capulets and the Montaigus in the third act, which leaves two people dead and intensifies the conflict, moves the production to a basketball hall. The process is very well choreographed and does not show the awkwardness that sometimes makes fights on stage seem embarrassing.

The only thing that is inappropriate is that the offspring of higher earners have no need to fight for hegemony in a sports facility with some rednecks. All you have to do is get a phone number from a cousin that you need to call for the job, and then be able to chat during the conversation in the way you learned to do below, if only with a lot of luck.

From a left-wing perspective, it is always sad to have to criticize directorial ideas that, based on progressive considerations, apply the right things to material that is unsuitable for them. In this production, hardly one idea fits the other, and it’s best if Clément doesn’t think of anything at all. In such passages a free space is created in which the musical characterization of the characters can unfold.

Julia Hansen’s stage offers a sometimes more, often less suitable setting for this. The public area of the Capulet villa appears modern and cool, as do the windows that protrude into the adjacent garden. We know this from many productions: the coldness of the powerful corresponds to their taste in furnishings, which aims at the uninhabitable. On the other hand, the school in which Father Laurent, who was demoted to religion teacher under Clément – a confidant of both Roméo and Juliette – teaches is more miserable.

Sports facilities that have been soaked for years by stale male sweat are almost as inhospitable a place as the morgue in the final scene. It remains unclear why Juliette’s bedroom, located in the Capulets’ aseptic home, looks like the back room of an outdated train station bar.

Passion is difficult to convey in such spaces; and when Roméo and Juliette take off each other’s clothes before their only night together, it seems just as awkward as it sometimes does in everyday life. After all, the two still have to concentrate on singing.

Elsa Dreisig is a strong-voiced Juliette, with top notes that are almost too powerful. But in doing so she gives the character what the direction denies, which shows a somewhat lax, rebellious brat. Despite all the resistance, Dreisig makes it believable what drives Juliette to give everything for love and go to her death. That can be said less of the Roméo, which Amitai Pati sings in a somewhat narrow, pressed voice. Some of the supporting characters are cast more convincingly, especially with Marina Prudenskaya as Juliette’s nurse and Ema Nikolovska as Stéphano, who belongs to the Montaigus gang; the latter – it must be so topical – is, according to Clément, a “non-binary person”.

The orchestra under Stefano Montanari accompanied with restraint, with luxuriously gentle sounds, especially from the strings, and behaved well even where a little more access would have been appropriate. Gounod’s late idea of adding a ballet episode after Juliette’s apparent death was probably not a good one. If he had anticipated the gymnastics that was now taking place on the State Opera stage, he would have left the matter alone.

Next performances: November 20th, 22nd and 24th

www.staatsoper-berlin.de

Become a member of the nd.Genossenschaft!

Since January 1, 2022, the »nd« will be published as an independent left-wing newspaper owned by the staff and readers. Be there and support media diversity and visible left-wing positions as a cooperative member. Fill out the membership application now.

More information on www.dasnd.de/genossenschaft

sbobet88 link sbobet link sbobet link slot demo