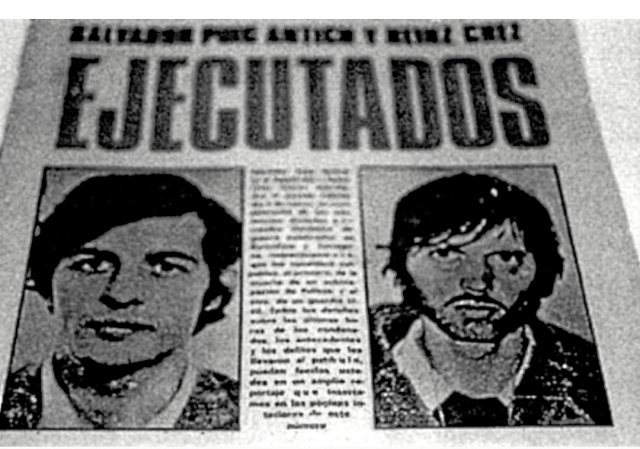

Salvador Puig Antich and Georg Michael Welzel were executed at the end of Spanish fascism.

Photo: Holger Uwe Schmitt

When the Franco dictatorship executed two convicts for the last time on March 2, 1974 – the Catalan anarchist Salvador Puig Antich and the GDR citizen Georg Michael Welzel – with the so-called garrotte, the medieval “strangling iron”, things were particularly cruel. The murder instrument itself is notorious: the garrote is an iron band that is placed around the condemned person’s neck and screwed tight until the victim suffocates.

But with Puig and Welzel, whose cases have nothing to do with each other and who were convicted completely independently of each other, everything is much worse. The executioners don’t know how to put the strangulation iron together correctly. In Welzel’s case, it is apparently the executioner’s first execution ever. So it takes half an hour until Welzel, who dies with a false identity, namely as the Polish citizen Heinrich Chez, is finally released. In order to cover up the scandalous circumstances of the execution, the military judge orders secrecy.

Convoluted biographies

The fact that Georg Michael Welzel, born in Cottbus in 1944, died in this horrible way is the result of a long chain of tragic events. Welzel, father of three children, was convicted three times for fleeing the republic between 1964 and 1970 and was only finally able to travel to the West in May 1972. There he worked in the Ruhr area for a few months until he traveled south in the autumn of that year and crossed the Spanish-French border at Port Bou. What happened there still gives rise to speculation today.

The filmmaker Raúl Riebenbauer, who reconstructed Welzel’s story in the early 2000s, writes that Welzel had a rifle taken from a German wine grower, with which he shot a Spanish civil guard quite suddenly in the bar of the Hospitalet de l’Infant campsite. Possibly the hatred of uniformed men was the motive for the crime, perhaps Welzel was also on drugs.

In any case, the fact is that Welzel takes on a different identity after his arrest. He claims to have been born in Szczecin as a Polish citizen and to have no living relatives. He also calls himself Heinz Ches – after his father’s middle name and his mother’s maiden name – which the Spanish police then changed to “Chez”. Because Welzel stuck to his story until his execution, his fate was unknown to the family for three decades. The children believe that their father died while fleeing the GDR; For the siblings, Georg Michael is simply missing. Only thanks to Riebenbauer’s research do the survivors find out the truth.

nd.DieWoche – our weekly newsletter

With our weekly newsletter nd.DieWoche look at the most important topics of the week and read them Highlights our Saturday edition on Friday. Get your free subscription here.

The second cruelly executed person that day is the anarchist Salvador Puig Antich, about whom director Manuel Huerga made the feature film “Salvador – Fight for Freedom” in 2006. This film adaptation, with Daniel Brühl in the lead role, made the resistance fighter Puig known to a wider public, but also contributed to a highly distorted historiography. Born in 1948, Puig was initially active in illegal grassroots unions as a young man and then became increasingly interested in anarchist ideas. He joins the newly founded Iberian Liberation Movement (Iberian Liberation Movement) and learns how to handle weapons and explosives from exiled anarcho-syndicalists of the CNT in the Occitan south of France.

Since his organization finances the printing of newspapers and leaflets through bank robberies, among other things, Puig took part in the armed actions from 1972 onwards. After the group seriously injures a bank employee during a robbery, the “Brigada Político-Social”, the Spanish dictatorship’s notorious secret service unit, sets its eyes on the anarchist group. Not least thanks to the systematic torture of suspects, the investigating officers quickly discovered the group and set up an ambush in September 1973. A shootout ensues in which Salvador Puig is seriously injured and a police officer is killed.

The garrote torture instrument has been used since the Middle Ages. Its use to murder Salvador Puig Antich and Georg Michael Welzel in 1974 was also the last known use ever.

Photo: Holger Uwe Schmitt

The fact that both Puig and Welzel are sentenced to death has not least to do with the crisis of the Franco regime. It is important to set two examples. In Puig’s case, the aim is to show political strength: at the beginning of 1974, dictator Franco was already seriously ill with Parkinson’s disease and his designated successor, the fascist naval admiral and head of government Luis Carrero Blanco, was killed by the Basque underground organization ETA in a spectacular attack in Madrid. Shortly before Christmas 1973, the Basque commandos blew up the prime minister’s car in the middle of the Spanish capital. Because the regime desperately wants to stop the armed groups, it is condemning Puig, who has not been identified as the shooter, to death as a deterrent.

But this condemnation leads to international protests. The painter Joan Mirò, who (like Pablo Picasso and Jean-Paul Sartre) had already expressed solidarity with ETA prisoners in 1970, painted the tryptochon “Hope of a condemned man” on the occasion of the Puig case, and his pardon was spread throughout Europe required. This is where Welzel, alias “Chez,” comes into play: To prove that Spain treats political resistance no differently than normal criminals, the regime orders the execution of a second “police murderer.” Georg Michael Welzel is the perfect victim of justice because no state in the world feels responsible for him. In the spring of 1974, Spain had no diplomatic relations with socialist Poland, and since “Chez” had declared that his parents had died during the Second World War, there was no fear of protests from relatives.

Film adaptation with flaws

The feature film “Salvador – Fight for Freedom” (2006), however, tends to obscure these political connections. Many film reviewers at the time considered it a particularly successful idea by the filmmakers to humanize prison guards and police officers of the dictatorship and to put them in an emotional relationship with Puig (played by Daniel Brühl). But this has little to do with the truth of the Francoist system. Special units like the one already mentioned Political-Social Brigade were notorious for torturing the souls out of suspects. The film’s thesis that Puig Antich blamed the armed struggle, namely the attack on Prime Minister Carrero Blanco, for his execution is certainly wrong. In reality, like many European leftists, the Catalan anarchists were delighted by the attack in 1973. After all, it was a fascist prime minister who was supposed to ensure the continued existence of the dictatorship. The horror of ETA’s bloody attacks only began years later.

Daniel Brühl and the film also do not do justice to the Puig Group’s political self-image. Puig and his comrades were not interested in lifestyle and rock music, as historical review often suggests, but rather they saw themselves in the tradition of the anti-fascist Maquis. Jean-Marc Rouillan, who lived with Puig in Barcelona and was ambushed by the police with him, founded the French organization in 1979 Direct Action, which broke with Catalan anarchism and instead cooperated with the Leninist RAF. Rouillan was imprisoned in France for more than 20 years.

One can only speculate about what Puig and Welzel would have done with their lives if they had not been miserably executed. The fact is, however, that the judicial crimes committed against them remain unpunished to this day. Because the courts in the EU refuse to take action in the matter, Salvador Puig’s relatives are still trying to bring the case to court in Argentina – as a serious human rights violation.

Subscribe to the “nd”

Being left is complicated.

We keep track!

With our digital promotional subscription you can read all issues of »nd« digitally (nd.App or nd.Epaper) for little money at home or on the go.

Subscribe now!