People died every day, in Leningrad during the blockade – in large numbers.

Photo: imago/ITAR-TASS

Odin, dwa, tri… “In the ten minutes that I sat at the window, I counted ten dead,” says Maria Burakova. On the day that the German fascist Wehrmacht surrounded and encircled her hometown, Leningrad, on the fateful September 8, 1941, she had wanted to celebrate her 15th birthday. »Suddenly bombs, bombs, bombs. Hellish noise,” the veteran remembers in the nd conversation: “Straschno bilo.” It was terrible.

Actually, the horror that the people in the city on the Neva suffered during the more than 900-day blockade, in the murderous stranglehold of the Germans, cannot be put into words. They fell over in the street, fell asleep on the park bench or at the empty kitchen table without waking up again, weakened by hunger, marked by illnesses and epidemics, exhausted by hard physical labor in the munitions factories or building ski jumps, parched or frozen, women, men, Children, old people. And yet: cinemas, theaters, concert halls and libraries remained open.

There was not a Leningrad family that did not suffer victims. Countless families were completely wiped out, says Leonid Berezin, who introduced me to Maria. Both belong to the Blokadniki, as the surviving “children” of the blockade call themselves. “We were more willing to die in a hail of bombs or starvation than to surrender,” emphasizes Leonid, who was twelve years old at the beginning of the blockade.

A quarter of a million Leningraders died in the first winter of the blockade alone. The barbaric aggressor is joined by the bitterest cold as a merciless enemy. The frozen Lake Ladoga remains the only connection to the hinterland, through which food and weapons reach the city and, above all, women and children are evacuated: it is soon called “Doroga schisni”, the road of life. But the trucks and horse-drawn sleighs that glide over the ice, as well as the barges that sail across the water in spring and summer, are also under constant fire from German planes.

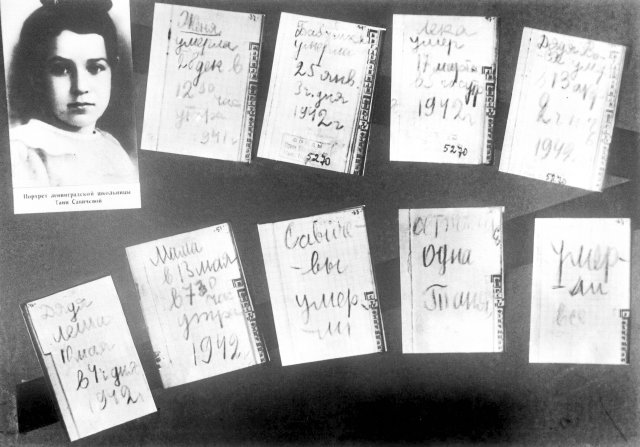

When Maria tells me what she observed on those harsh winter days in 1942 when temperatures were minus 40 degrees, I think of Tanya Savitscheva. The eleven-year-old recorded the deaths in her family in a small notebook. Nine pages on which names, dates and times are written in childlike, awkward writing: “Zhenya died on December 28th at 12:00 in the morning, 1941. Babushka died on January 25th, at 3:00 in the afternoon, 1942. Ljosha died on March 17th at 5:00 p.m “A.M. ” And on the last sheet written on you can read: “Ostalas odna Tanja.” Only Tanja is left. The girl died on July 1, 1944 at the age of 14. Her diary is presented by the Soviet prosecution in the Nuremberg tribunal against the Nazis and major war criminals. Tanja’s notepad, like Anne Frank’s diary, was already known to schoolchildren in the GDR. And today?

“Govorit Leningrad” – This is Leningrad speaking: Olga Fyodorovna Bergholz’s voice comes through the airwaves, radios and loudspeakers in public places to those trapped several times a day to encourage them. Even if the news from the front for a long time, until the Battle of Stalingrad, did not bode well and could not raise hopes. The impact of aerial bombs and continuous artillery fire from the Wehrmacht cannot chase the young woman, daughter of a doctor of German origin, who was briefly arrested during the years of the Great Terror, from her place at the microphone. In 1942, the aspiring poet wrote the “Leningrad Poem” as a homage to her starving compatriots. Four years later, her memories and radio speeches appeared under the title “Govorit Leningrad”; However, the book is soon confiscated and banned because it does not correspond to the heroic epic prescribed by Stalin.

This does not affect her reputation or people’s gratitude towards her. She was, is and remains a legend – similar to Yuri Levitan, who since June 22, 1941, the day Hitler’s Germany attacked the Soviet Union, has started the state radio news with the words: “Bnimaniye, govorit Moskva” – attention, here speaks Moscow. And this also after the station was relocated to Yekaterinburg in view of the threatening German army marching towards the capital, only to move on to Kuibyshev (today Samara) in 1943.

The people of Leningrad also lacked drinking water.

Photo: imago/ITAR-TASS

Dressed in a fire protection suit, a man sits in the loft of the Leningrad Conservatory, bent over a desk, conjuring up notes on paper. Days and nights at a time, ready to stop work at any time to put out fires. The composer refuses the request to leave the city. Ultimately, Dmitri Shostakovich has to submit: After he has completed the first three movements of his Seventh Symphony, he and his family are flown to Kuibyshev, where he completes the work. In the distant city on the Volga he experienced its premiere on March 5, 1942, intoned by the Bolshoi Theater orchestra, which had also been evacuated. A few days later, the symphony that will be called the “Leningrader” sounds in Moscow, despite shrill sirens sounding the air alarm. It is played in London and New York in the summer of the year.

On October 7, 1941, Hitler announced: “Leningrad must be starved.” The radio symphony orchestra of the city that the dictator initially wanted to take over in Berlin responded defiantly with the “Ninth” by the German composer Ludwig van Beethoven. The concert on November 8th will also be broadcast live on the BBC. And British Prime Minister Winston Churchill would later pay tribute to the unwavering resistance of the Soviet people against an overwhelming, insidious enemy in his “History of the Second World War,” which won the Nobel Prize in Literature.

“Gorod geroi” – city of heroes. After the liberation from fascism, twelve Soviet cities and the Brest Fortress received this honorary title, whose garrison, 9,000 Red Army soldiers, offered bitter resistance to the 17,000 soldiers of a German infantry division for seven days, from the first day of aggression to June 27th. Although some hero cities in the post-Soviet states are no longer identified in Cyrillic letters, such as Odessa on the Black Sea, their defenders and the victims of the civilian population during the “Great Patriotic War” are not forgotten there either and are honored just as they were in Moscow. Leningrad, Sevastopol and Volgograd.

The suffering and death of the people of Leningrad did not end with the lifting of the blockade on January 27, 1944. Neither does it elsewhere. Tens of thousands are still losing their lives, not just as members of the Red Army on the front that is rolling westward, kilometer by kilometer, towards the German capital. They also succumb to the consequences of the Nazis’ openly declared campaign of annihilation against the “Jewish-Bolshevik, Slavic subhumans,” as Goebbels’ propaganda sounded. A announced genocide.

On January 27, 1945, the Red Army reached Auschwitz, synonymous with the murder of six million Jews. The number of people murdered in this German concentration and extermination camp is estimated at one to one and a half million. The victims of the peoples of the former USSR are estimated at 27 million. Over a million people died during the blockade in Leningrad alone.

The death chronicle of Tanya Savitscheva

Photo: imago/ITAR-TASS

Maria and Leonid moved to Germany with their families in the early 1990s. They cannot forgive the horror and pain inflicted on them and their families in the German name. They do not make the accusation of collective guilt. Of course there was hatred for the “Nyemzi” among the victors, the soldiers as well as the population of the Soviet Union. Half a decade later, the first young Germans traveled to the USSR, invited to study.

Gerd Kaiser, who studied history in Moscow in the 1950s and wrote a number of historical articles for this newspaper, remembers: »One of my roommates in the Obschshitje, in the student hostel, was a Belarusian who was blind in one eye after a head injury. An Estonian only had limited use of one arm. And one Russian had a huge scar clearly visible on his head from a German bayonet. Some were also still wearing their faded, worn-out Red Army uniform jackets and coats.” And the mother of the author of these lines spoke with great respect about her German studies professor in Leningrad, who recited Goethe and Heine by heart and recommended her thesis on the German journalist Carl to write by Ossietzky.

nd.DieWoche – our weekly newsletter

With our weekly newsletter nd.DieWoche look at the most important topics of the week and read them Highlights our Saturday edition on Friday. Get your free subscription here.

The double meaning of January 27th, the liberation of Leningrad and Auschwitz, is referred to in a statement published on Friday by the Association of those Persecuted by the Nazi Regime – Association of Antifascists (VVN-BdA), which describes the federal government’s treatment of the survivors of the German conquest. and war of annihilation against the Soviet Union as “scandalous”. Last fall, survivors of the Leningrad blockade, now numbering less than 60,000, wrote an open letter to Berlin asking that the compensation promised to Jewish survivors be extended “to all blockade victims still alive today, regardless of their ethnicity.” The German-Fascist starvation murder plans included “no exceptions based on nationality.” An answer is still pending.

It took over four decades for the crimes of the Wehrmacht in the Federal Republic to be uncovered and made public. Should another 40 years pass until there are no more survivors of the German-fascist war of conquest and annihilation in the East?

Read the speech by Russian writer Daniil Granin ten years ago in the German Bundestag on Monday.

Subscribe to the “nd”

Being left is complicated.

We keep track!

With our digital promotional subscription you can read all issues of »nd« digitally (nd.App or nd.Epaper) for little money at home or on the go.

Subscribe now!

judi bola sbobet88 judi bola online sbobet