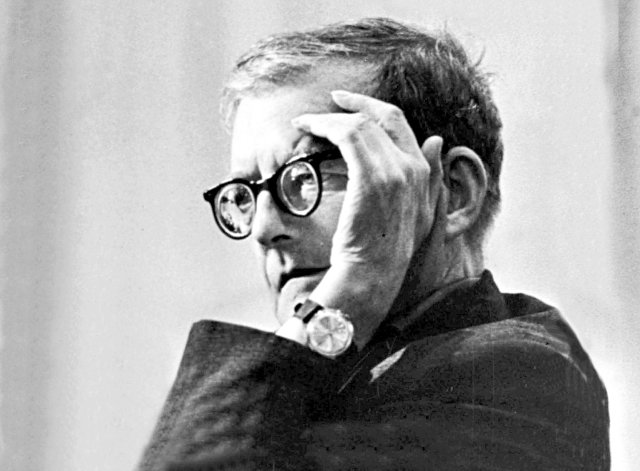

Yes, are we at the Olympics? Schostakovich, 1972.

Foto: imago/ITAR-TASS

The sheet smashes a veritable ink, the drums swirl, the orchestra uses with all its might and increases chromatically step by step until the festive music is unloaded at its climax. Yes, are we at the Olympics?

The older people may remember: The “festive overture op. 96”, by Dmitri Schostakovich in 1954 for the celebrations of the Bolschoi Theater on the 37th anniversary of the October Revolution, was the musical signature topic in 1980, the title shower of the Olympic Games in Moscow. It is an excellently composed musical hideousness, a major high-gloss music, until then the playful clarinet melody appears and seems to be transferred to a kind of lively cartoon.

Ann-Katrin Zimmermann pointed out the ambiguity of this melody, which Schostakovich also used in his opera “Lady Macbeth von Mzensk” and assigned the drunkenbold there, who discovered the murdered husband, alerted the police and spoils the rushing wedding festival of the lady. But room, nothing goes wrong here in the overture, everything ends after a good five minutes in a new, mighty major-Zinnober full of champagne brilliance.

In May, the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra had set this “festive overture” at the beginning of its 18-day Schostakovich festival. It was a brave but also obvious decision, since this strange piece shows a composer who willingly and liked to write order music on public occasions, and also that Schostakovich of the Soviet Union remained loyal for all times – despite all of this. To this day, the “festive overture” is one of the composer’s most played in Russia and one of only two works that the master ever conducted.

Dmitri Schostakovich died on August 9, 1975 in Moscow at the age of 68. In the west there was a narrative in which the name Schostakovich is hardly ever called without its antipoden Stalin. This is primarily to be attributed to the questionable “memoirs”, which Solomon Volkov published in 1979 in the USA and the FRG and which, according to everything you now know, represent a fake. His widow Irina Antonovna Schostakovich later said that Volkov had “hit her husband maybe three or four times”: “He was never a close friend. He never came to eat. I really can’t imagine how he claims to have collected so much material for such a thick book. «

Schostakovich’s son Maxim said in 1981 after his escape to the west that Volkov’s book was »a book above my father, not von my father «. Five years later, Maxim knew what you wanted to hear in the West, and said in a BBC interview that the book was accurate in the description of the hardness of life under totalitarian rule. Slavist Brigitte Van Kann pointed out on Deutschlandfunk that Volkov never presented the alleged original manuscript signed by the composer, and he was also remote conferences on the topic. She describes these supposed memoirs, written down by Volkov, as a “farce”, as a – after all – “ingenious fake”.

Ultimately, Julian Barnes’ Schostakowitsch-Roman “The noise of Zeit” (2016) on Volkov’s fake memoirs is also based. Barnes constructed a talking picture for this: “They always got you in the middle of the night. So, in order not to be dragged out of the apartment in her pajamas, he preferred to go to bed, at the top of the ceiling, a finished little suitcase next to him on the floor. ”A little later, the composer spends his sleepless nights, waiting for Stalin’s henchmen, in front of the apartment door, next to the elevator. This is a well -invented, stylized picture in a novel, but this should do without reality. It is quite likely that the composer had to expect his arrest, especially in the years of terrible Stalinist “cleansing”. It may be that he also packed a suitcase with the most necessary. Everything else is invented, even if this picture is now used as a real fact in many texts on Schostakovich.

The truth should be more complicated. One can confidently assume that Schostakovich was not only a veritable anti-fascist, as is not least evident in the great seventh, his fascinating »Leningrad« symphony. He wrote it in the face and awareness of the 900 -day siege of Leningrad by the German Wehrmacht, one of the great war crimes of National Socialist Germany, and devoted them to “our fight against fascism, our inevitable victory over the enemy and Leningrad, my hometown”. For this he received the Stalin Prize.

This 7th symphony caused a sensation worldwide: Leopold Stokowski conducted it in 1943 in a US military camp before thousands of cheering GIS (and as an encore, he let the orchestra play the “international”, at the time the national anthem of the Soviet Union). That was troop supervision in a war in which the Soviet Union and the United States were concerned with something, namely the fight against the fascist German Empire, which the Soviet Union had to pay with ten million dead soldiers and another million civil victims.

Schostakovich was undoubtedly a sympathizer of the Russian Revolution and the early Bolshevik Soviet Union, which was not only a country full of artistic possibilities and freedom until around 1929 until around 1929. There was an enormous extent of grassroots democratic initiatives, mass mobilization and freedom of art.

Lenin was well for civil cultural life. In 1920 he dissolved the proletary cultural movement founded before the October Revolution, but he subordinated the People’s Commissioner for Education, which the Schöngeist Anatoli Lunatsharski headed until 1929. This was a liberal era of progressive cultural policy, which the Soviet culture and the arts were extremely fueled until the cultural system was instrumentalized and unhanged by Stalin after 1929.

Schostakovich announced in 1967 that “the revolution”, ie the ten months from February to November 1917, made him a composer: “That may sound exaggerated – from then on I felt called to compose.”

sbobet judi bola sbobet sbobet