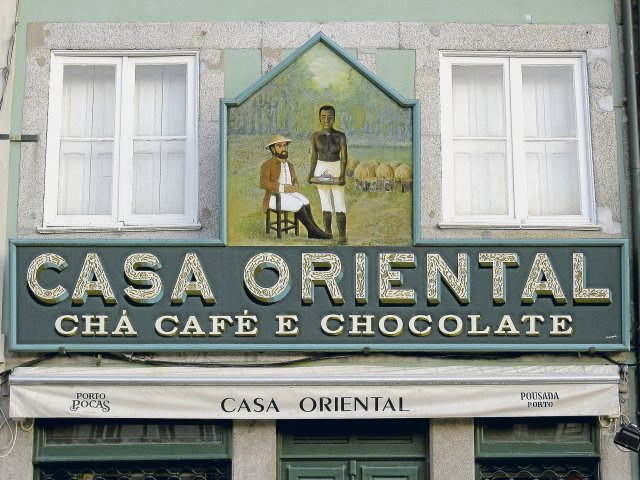

Colonial bestseller: Fine chocolate was long reserved for the aristocracy. Their democratization was also accompanied by an improvement in manufacturing conditions.

Photo: A. Vossberg/VISUM

Most often, cocoa is used to prepare a drink that the Indians call chocolate. … Drinking is common there, both by the natives and the Spaniards. Once you get used to the drink, the enjoyment becomes a passion,” wrote the Italian merchant Francesco Carletti in his report “Journey around the World” in 1594. It was Spaniards who were the first Europeans to come into contact with the cocoa plant in the 16th century during the violent subjugation of the Mayan and Aztec empires. To this day, the origin of chocolate is attributed to these two advanced cultures and can be found in advertising slogans à la Mayan or Aztec gold. Archaeologists were able to prove that the cocoa tree was cultivated over 5,000 years ago by societies in what is now the border area between Ecuador and Peru. The archaeological finds suggest that there must have been trade and exchange relationships between Central and South America for centuries.

Rise of a luxury food

The conquistadors were therefore able to make use of the expertise of the indigenous population, which they had developed over long periods of time in the cultivation and processing of cocoa. Or they simply occupied some of the existing cultivated areas. In contrast to tobacco, potatoes or corn, the cocoa plant proved to be climatically demanding and could not be transported to Europe. Estimates suggest that between 80 and 90 percent of the indigenous population of Mexico and Central America died due to the brutal actions of the Spanish colonizers and imported diseases. To compensate for the lack of labor, the Europeans stole people from the West African coast, shipped them across the Atlantic like goods and forced them to work as slaves on the expanding plantations.

From the beginning of the 17th century, cocoa regularly appeared in the cargo registers of Spanish overseas travelers. At that time, chocolate was a luxury drink of the aristocracy in Europe. Starting from the Spanish court, it first spread to aristocratic circles and European court societies. From the 18th century onwards, it became accessible to the middle class through coffee houses or so-called chocolate shops. Chocolate was considered health-promoting and was a prestige drink, on average more expensive than a cup of coffee. In addition to the production costs, the high price also resulted from expensive spices that were added to the chocolate, such as vanilla, chili, cinnamon or cloves.

Chocolate only became a consumer product for the masses as a result of industrialization. Machines made the laborious process of converting cocoa beans into chocolate paste more efficient and cost-effective. Further steps on the way to the chocolate bar we know today were the inventions of cocoa and milk powder in the 19th century. At the beginning of the 20th century, working families could finally afford chocolate, which was both a luxury item and a quick source of energy.

Colonial value chain

With increasing demand from Europe, the cocoa plant migrated from Mexico to plantations in the Caribbean over the centuries. It only reached the African continent at the beginning of the 19th century with the first cultivations on the islands off the West African coast. The Ghanaian craftsman Tetteh Quarshie is said to have secretly smuggled the first cocoa plant from the then Spanish-occupied island of Fernando Pó, now Bioko, to the mainland. By setting up his own cocoa plantation – which can still be visited in Ghana today – he resisted the Spanish-Portuguese monopoly. In Ghana, Tetteh Quarshie is known as the “father of the cocoa industry”.

Despite this resistant practice, the cacao plant is one of many examples of how European colonialism profoundly changed local fauna and agriculture. Today, the West African countries, especially Ghana and Ivory Coast, are among the largest cocoa producers in the world with a share of around 70 percent – but this does not bring in much for their state coffers. In fact, little has changed in the colonial value chain for many raw materials, including cocoa: the processing and refining of raw materials still takes place in countries in the Global North, which also make the greatest profits. According to the Inkota network, cocoa farmers receive just 8 cents from the price of an average bar of chocolate, while chocolate companies make four times as much profit. The majority of the world’s 5.5 million cocoa farmers live below the poverty line. This means that in West Africa alone around 1.5 million children have to work on the cocoa plantations.

But stop! Wasn’t there a movement long ago that campaigned for a fair distribution of profits between South and North? The idea of fair trade, in which producers receive a living wage, developed in the 1950s in the context of Christian charitable institutions and was carried forward in the following years by various solidarity campaigns. The first “third world stores” opened their doors in the 1970s. In addition to selling fairly traded goods, the aim of the shops was (and is) to provide political education and create critical awareness of unequal global economic structures. A lot has happened in the Fairtrade sector since then. The range of fairly traded products has expanded, the trade organizations have developed various standardization and certification mechanisms and have become enormously professional – and unfortunately also depoliticized.

Fairtrade best seller

Fairtrade products have increasingly degenerated into feel-good products that are offered in every supermarket or in the range of large corporations such as Nestlé or Starbucks. This so-called fairwashing not only hides the fact that many global corporations disregard the rights of their workers in the Global North. The standards of certificates such as the Rainforest Alliance seal, which is found on Aldi products, do not guarantee a living wage for producers in the Global South. If you want to find your way in the seal jungle, you have to invest in political education and rely on information materials from NGOs like Inkota.

Paradoxically, many of the former colonial products are now among the top sellers of fair trade goods: coffee, tropical fruits, spices, sugar and chocolate. Consumers in the Global North are still in the powerful position of deciding whether they “do something good” for people in the Global South or even promote their “development”. The requirements imposed on producers through Fairtrade certifications are of course sensible, but can also be understood as a dictate. Only those who stick to the rules will receive the bonus for survival – at least if the pre-announced tests are carried out by certification bodies.

And there is also a strange colonial continuity in the colorful advertising images for chocolate, even with fair trade products. Images of small farmers dressed in traditional or folkloristic clothing are often used here, who, photographed in a beautiful natural landscape, smile gratefully into the camera – the serving Sarotti-M. sends greetings. The dichotomies of modern versus traditional or exotic, of progressive versus underdeveloped, which go back to colonial ideologies, are simply recalled in the consumer’s visual memory.

Finally fair?

So would you rather not have chocolate at Easter? Not necessarily. Of course there are also positive developments on the cocoa market. There are excellent fair trade organizations that strive to reduce hierarchies in collaboration as much as possible. A large number of NGOs have also been fighting for decades to make the local chocolate empires more responsible. The new EU supply chain law, which was passed by the EU Council on March 15, 2024 despite Germany’s abstention, could also help.

In addition, more and more producers in the Global South are asking themselves why they shouldn’t process and sell their raw materials themselves. The government of Ghana, for example, announced four years ago that it wanted to boost domestic production. To this end, Ghana has joined forces with neighboring Ivory Coast, among others, to set minimum prices for cocoa beans. In addition, incentives are being created to set up industrial processing of cocoa beans locally – which is already showing success. The website of the Ghanaian chocolate company Fair Afrique says almost succinctly: “We don’t donate anything to Africa. We simply produce in the country of origin and pay fair salaries.”

Katrin Dietrich is a sociologist and works at the iz3w (3rd World Information Center).

Become a member of the nd.Genossenschaft!

Since January 1, 2022, the »nd« will be published as an independent left-wing newspaper owned by the staff and readers. Be there and support media diversity and visible left-wing positions as a cooperative member. Fill out the membership form now.

More information on www.dasnd.de/genossenschaft

link sbobet sbobet judi bola judi bola online