Matthias Poignavent, 37, technical director, is proud of the Afrique station in L’Île-Saint-Denis.

Photo: nd/Jirka Grahl

Strange sounds float over this evening Park La Villette in the northeast of Paris: In front of the small stage, a few dozen people sit on picnic blankets and listen to the strange sounds of a morin chuur, the Mongolian “violin with a horse’s head,” accompanied by roaring overtone singing. The light of the sun has a reddish tint, the scent of fried vegetables mixes with a breath that blows from the neighboring Canal de St. Denis. “Welcome to Mongolia House,” says Saruulsaikhan Ochir.

The 22-year-old from Ulaanbaatar works full-time for Mongolian television, and now she can welcome guests in the Mongolian pavilion in Paris: “This is our first time at the Olympics,” says Ochir. “It’s all very exciting for us.”

There is space for 400 people on the site, you can visit a yurt, have your name painted on a piece of Mongolian calligraphy on a sheet of parchment or eat Mongolian food: steamed Buuz dumplings, in which only beef is cooked instead of yak meat. “Mongolians serve their guests only the best, and in large quantities,” smiles host Ochir. “The people in Paris should know about it.”

Saruulsaikhan Ochir from Ulaanbaatar welcomes guests to the Mongolia House.

Photo: nd/Jirka Grahl

The world is a guest in Paris – not just in the sports facilities. All you have to do is walk further from Mongolia House and you can explore a good part of the world in this park alone: Casa Brazil, Serbian House, La Maison Slovaque, South Africa House or Casa Mexico. There are 54 Nations Houses throughout Paris, 14 of which are located here in La Villette alone: the city calls its festival site the Park of Nations, which is picturesquely crossed by canals. Tens of thousands flock here every evening. The former slaughterhouse site extends over 55 hectares – the largest park in the city, more than twice the size of the Tuileries Garden, over which the kitschy golden balloon with the Olympic flame lights up every evening: a second moon, Olympia as a cosmic phenomenon.

25,000 people in the Club de France

Just five minutes away from the Mongolian yurt is the Club de France site, the host branch for the local fans: 25,000 people come here every evening to cheer on their athletes on the lawn in front of the giant screens. When another judoka wins gold, cheers roar through the 19th arrondissement as if there were a stadium here. Tickets for the club cost five euros and are always sold out.

Like the “Team NL Huis” right next door: 7,000 Oranje fans pay 30 euros admission every evening and lounge on the deckchairs in front of the big screens. On the grounds is the Le Zenith concert hall, where Snollebollekes, the carnival band to whose music Dutch fans jumped back and forth so spectacularly at the European Football Championships in Germany, performs. Recently, the gold medalists in rowing were carried through the arena on the hands of fans. Holland celebrates, people are among themselves: few Parisians want to pay an entrance fee of 30 euros.

The complete opposite of the Oranje House is just a few minutes’ walk away: “Volia Space – Ukraine” is written above the entrance to Le Trabendo. Where night owls usually dance to the sets of popular DJs, the war-torn country has set up its Olympic House. However, no one here feels like celebrating. Not even the incumbent Ukrainian sports minister, who traveled to Paris for a few days and is now waiting for visitors with the house team.

Matwij Bidnyi is wearing a polo shirt that stretches tightly over his muscular chest. The 44-year-old is a former national team bodybuilder and could almost pass for an athlete. Nevertheless, he speaks quietly and uses reserved words. Is it even possible to celebrate sport these days, Minister? “Phew!” he sighs. »Good question, difficult question. But look around, do you see anyone celebrating?”

Destroyed rows of seats at the Kharkiv Stadium in the House of Ukraine

Photo: nd/Jirka Grahl

In fact, the house, which can accommodate 900 people, is more of an exhibition than a festival site. In the courtyard of the Volia Space, three rows of seats from the Kharkiv Stadium are installed under plane trees in front of a wall. According to the Ministry of Sports, more than 520 sports facilities were destroyed in the war. The cracks in the seat shells give an idea of the force with which Russian bombs hit. The slogan is everywhere: “The will to win”. The will to win, in sport but also in war. “We are here, that alone is a victory,” says Bidnyi. Does he believe in the Olympic Peace? »A terrorist state like the aggressor doesn’t stick to it anyway: Georgia in 2008, Crimea in 2014, Ukraine in 2022. How is the Olympic Peace supposed to succeed?”

Taiwan is holding back

Politics doesn’t avoid Olympia, which can also be seen in the neighboring house. You can’t tell from the outside which nation resides here. Two “Vs” in rainbow colors keep visitors guessing: Is this the Pride House, is this where the LGBT community celebrates? “No, no,” laughs Lin Kun Ying, the artistic director of the house project with DJs, video art and Taiwanese opera. »We represent Taiwan here. But according to the IOC rules, we are not allowed to call ourselves that.”

In fact, due to political pressure from China at the Olympics, the breakaway island republic can only be referred to as Chinese Taipei. “Chinese Taipei, we didn’t want to use that here,” says Lin. Instead, use the V as a symbol of victory. »And we chose the rainbow colors because Taiwan is so modern and cosmopolitan. We are the only Asian country where same-sex marriages are allowed.” Drag queens from Thailand also appear in the Taiwan House in Paris: “Nymphia Wind is coming on Thursday!” beams Lin, who is known in his homeland for spectacular installations . »She’s a superstar! Come by, don’t miss it!”

Africa celebrates in the suburbs

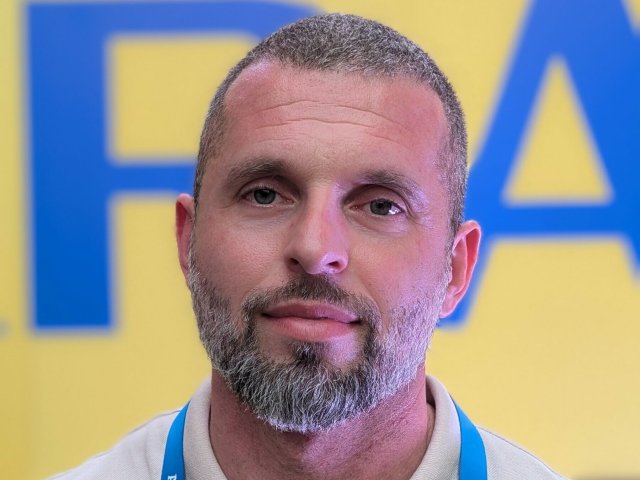

Sportminister Bidnyi (Ukraine)

Photo: nd/Jirka Grahl

1009 athletes from Africa are competing in Paris; South Africa’s Olympic Committee is the only one of 54 NOKs to have its own pavilion in La Villette. The balance of power in the world is also reflected at the Olympics. But thanks to the foresight of Mohamed Gnabaly, Green mayor of the small Paris suburb of L’Île-Saint-Denis, another 16 nations will have their common festival venue at the Paris 2024 Games: the Afrique station in L’Île-Saint-Denis in the stadium Robert Cesar. In the middle of the banlieues, those suburbs where poverty is rampant.

On Sunday evenings there is a huge crowd at the station. On this day, Senegal is the host at Station Afrique, the country where the roots of Mayor Gnabaly lie, who was able to attract various NOCs, the central government and various sponsors to finance the project.

There are long queues to get in; Senegal’s superstar Youssou N’Dour will be singing on the big stage today. Entrance fee of 20 euros is still a piece of cake for the well-known singer. “Entry is actually free,” says Matthias Poignavent, 37, technical director of the Afrique station. “But with the 20 euros we can ensure that we are not overrun.” 3,000 people are allowed in, almost all visitors come from the small suburb, which is stretched out on an island on the Seine: 8,500 inhabitants, 84 nationalities, one of them is one of the poorest Department of France, the 93rd

The station has a water playground for the children, a screen with loungers and a lot of stands where the countries present themselves. “Even as a small town with a poor population, you can think big,” says Matthias Poignavent. When Youssou N’Dour finally comes on stage to the cheers of the audience, 3,000 people are dancing. The banlieues celebrate themselves.

A house for 16 African countries: Senegal was celebrated on Sunday.

Photo: L’Île-Saint-Denis

Subscribe to the “nd”

Being left is complicated.

We keep track!

With our digital promotional subscription you can read all issues of »nd« digitally (nd.App or nd.Epaper) for little money at home or on the go.

Subscribe now!

link sbobet link sbobet judi bola online judi bola