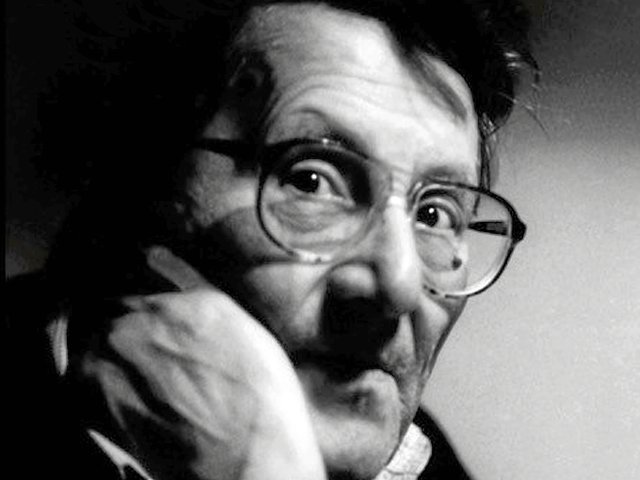

Peter Ruben (1933–2024)

Photo: Camilla Elle

He was the best-known unknown among the GDR philosophers. The “Philosophenlexikon” published in 1982 by the (East) Berlin Dietz Verlag, which is widely used even outside academic circles, does not mention Peter Ruben’s name. No wonder, the previous year he had been expelled from the SED for “revisionism” and banned from teaching and publishing, which lasted until 1989.

Of course, we philosophy students at Humboldt University knew his name, but more as a rumor. There is someone who is trying to drive out of Marxist-Leninist philosophy the dogmatism that was founded in Stalin’s “On Dialectical and Historical Materialism” of 1938. It was said at the time that this writing was intended to eliminate the “chaotic conditions” within Marxism that had previously prevailed. Instead of one’s own thinking and creative arguments, it was now time to repeat prefabricated ideological shells. Anyone who did not comply was declared a dissident. Nikolai Bukharin was killed in a show trial (also in 1938). Lenin, who invented the “New Economic Policy” (NÖP), called him “the darling of the party”.

The GDR philosophy cannot be understood independently of this, as Ruben notes: “It is therefore not a foreign body in German intellectual history, but one of its post-war figures, i.e. an expression of the spirit of a time that is now at an end.” The fates of strong personalities confirm the tragic tendency that he describes from his own experience as follows: “Anyone who has dedicated themselves to philosophy in the GDR, usually at a young age for completely ordinary reasons of gaining knowledge, has had career opportunities opened up for them, which are from being a member of the Central Committee of the SED up to an inmate in a penitentiary.”

In the historical context of its creation, “GDR philosophy could have been nothing more than a philosophy on its knees.” However, Ruben himself – and a few others – did not give in and had to pay the price. They included moral authorities of the communist resistance such as Robert Havemann, sentenced to death by the Nazis in 1943 for “high treason.” In 1963/64 he gave his lectures at the Humboldt University on scientific aspects of philosophical problems, which later caused a sensation as “Dialectics without Dogma”. In the same year he was expelled from the SED and banned from teaching. In 1977, Rudolf Bahro was sentenced to eight years in prison for “The Alternative” on nonsensical espionage charges, of which he served two.

nd.DieWoche – our weekly newsletter

With our weekly newsletter nd.DailyWords look at the most important topics of the week and read them Highlights our Saturday edition on Friday. Get your free subscription here.

A frightening picture emerges: the Stalinist-style communists treated original minds in their own ranks as if they were enemies who needed to be rendered harmless. Ruben recognized this early on as a cardinal development problem in GDR society. He repeatedly thinks about work as a form of human metabolism with nature.

Born in Berlin in 1933, Peter Ruben began studying philosophy here in 1955, rather than in Leipzig, with Ernst Bloch (who did not seem “scientific” enough to him), with the minor subjects mathematics and physics, which became important to him in order to use mathematical models to understand society to be able to map processes. In 1956, many things seemed to be possible, including that Stalin would come to power after the 20th century. Party congress of the CPSU is now finally “leaving the room,” as Stefan Heym brings the illusion of a “thaw” into the picture. However, the brief “thaw” is followed by more frost. The sentencing of Wolfgang Harich and Walter Janka to long prison sentences shows that things continue in the old style. Any opposition is suppressed.

In 1958, Ruben got caught up in a campaign against dissidents, was expelled from the SED, expelled from the register and sent to “prove his skills in production” as an unskilled laborer in the construction of Berlin-Schönefeld airport. Three years later he was allowed to continue his studies at the Humboldt University and received his doctorate at the Institute of Philosophy in 1969 with the thesis: “Mechanics and Dialectics. An epistemological-philosophical study of physical behavior«. For Ruben, “general work,” which for Marx means a form of real reappropriation of one’s own alienation, i.e. active ownership consciousness, leads to science. This is definitely a new emphasis: ownership consciousness as an active process of penetration is not a mere attribution. (Ruben sees his view confirmed by the non-ownership role of workers during the fall of communism in 1989.)

When he wanted to concretize these ideas in a joint project with the GDR economist Hans Wagner in 1977, the SED leadership did not take this as an innovative impetus, but instead began an accompaniment against Ruben and set up a commission whose predictable guilty verdict was: revisionism. The usual consequences: exclusion from the party, ban on teaching and publication, dismissal. The absurd situation: The economic crisis, in which the rapidly increasing prices of raw materials from the Soviet Union also played a part, is increasingly affecting the GDR economy. You receive helpful loans from the West and at the same time tighten the ideological reins in the country – thus preventing any innovation in society.

After international protests, Ruben continued to work at the academy institute – far away from students – but he was essentially banned from contact and later called these years until the fall of the Berlin Wall his “inner emigration”. A paradoxical situation: He can concern himself undisturbed with questions of modern development theory, for which he makes a connection between Marx and the “Kontratjev cycle” of the “Long Waves” of 1926 (meaning economic and crisis cycles lasting several decades). Or deals with the economist Joseph Schumpeter, who sees technical innovation as social destabilization, which contains both opportunities and threats.

The “history of communist philosophy,” Ruben writes, is a “process with many black holes and white spots.” The PDS rehabilitated him after the fall of the Wall. In June 1990, the staff of the academy institute elected him director – this was completed in the fall. But Ruben is now finally present in public, founds the magazine “Berliner Debate INITIAL”, becomes an employee at the European University Viadrina Frankfurt (Oder), and publishes a lot.

But unfortunately, at a crucial time, his impact was taken away and he was senselessly sidelined in the search for innovative forces in society. Much of what came after 1990 was inevitably retrospective, such as his recommended essay: “On the Place of the GDR in German History” from 1998. Ulbricht, who achieved the feat of becoming both Stalin’s man and also the de-Stalinizer Khrushchev (but… not Brezhnev’s), pushed forward the economic reform in the 1960s through which the GDR could have become a modern industrial and scientific state. The fact that he is following Bukharin’s NÖP is not said out loud, but the old officials know full well that it is against them. Ruben notes: “Ulbricht adamantly insists on the ‘revisionist’ assumption that the plan will be tested by the market, and on top of that makes the fundamental mistake of telling the Soviet comrades at their party conference about his meeting with Lenin and thus disappears from the communist stage for good Management officials.«

What happiness it was to experience that last spring the edition of Peter Ruben’s “Collected Philosophical Writings” supported by the Clara Zetkin Foundation was presented in four volumes, published by Verlag am Park – together with Peter Ruben, his wife Camilla Warnke and numerous colleagues. A historical-philosophical treasure trove from which we now have to draw.

On October 20th, Peter Ruben, who had been seriously ill for a long time, died in Berlin at the age of 90.