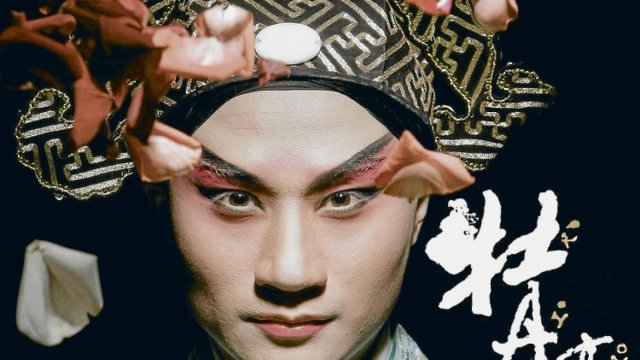

A sea of characters: The Chinese opera “Peony Pavilion” from the 16th century

Photo: © HKCO

Before Western drama took hold, Chinese stage art was consistently musical theater. The numerous local schools had their own rules, and these rules had to be known. Nothing was a naturalistic imitation of reality, everything was conveyed through signs. The stage managed with a minimum of props. The color of the garment, the way of walking or the posture indicated the social rank of the figures. A differentiated gesture, right down to the position of the fingers, represented feelings; as well as facial expressions, unless masks were used anyway. Finally, the singing, which has little to do with that in Western opera, uses a variety of registers: from the throaty to the falsetto, from the almost speaking to the melodic.

But the melody is perhaps secondary. The individual tone has its development. Of course, a Western violin would also sound choppy if it conveyed the quarter note C sharp to the following note without any approach or decay and, if necessary, phrasing. But in traditional East Asian music, the vibration of the single note has an incomparably greater importance. As far as singing is concerned, this is similar to Chinese as a tonal language, that is, a language in which the up or down sound of the vowels distinguishes meaning.

Chinese opera hardly relied on innovation. Of course, stories and presentation styles have changed over the centuries, but people didn’t go to the theater to experience an exciting story with an uncertain outcome. The stories were varied here and there, but their basic structure was familiar. People enjoyed the virtuosity of the performance. You probably rarely saw the whole of the very extensive pieces, but instead sat down for a few hours in the audience, which was by no means quiet. Sergei Tretyakov, for example, described in one of his travel books how the Peking Opera was a people’s theater just 100 years ago.

The best-known work in the development of the Kun opera is “The Peony Pavilion” by Tan Xianzu, premiered in 1598. During the approximately 22-hour running time, Tan has around 160 people appear and combines a love story with political events, without neglecting the spiritual world . The director and actor Zhang Jun has concentrated the whole thing in perhaps a little short 70 minutes, which brings the love story: how the aspiring scholar Liu Mengmei and the young woman Du Liniang dream of each other, Liniang dies, Mengmei recognizes the lover in the dream in a picture and Finally – thanks to benevolent spirits – the two become a couple.

How do you write a review of a performance like this? Unfortunately, the reviewer knows enough to suspect what he should have known. Unlike him, every fish seller in Shanghai in 1924 would not only have understood what a gesture signified at a particular point in the action, but would also have been able to judge how skillfully the gesture was executed.

Art, like everything beautiful, requires work.

–

So there are only two things left here. The first is ignorant praise: for the richness of sounds, the splendor of the costumes, the stylized elegance of the movements. But the praise also goes – on this level – to the organizers of the Lausitz Festival. They moved the pagan game to the monastery ruins of Oybin Castle; and experiencing the alternation of dreams, death and new life in the gradually falling darkness within the old walls was atmospheric and was appropriately applauded.

But it was just a mood and couldn’t be knowledge. “Anderselbst” is the motto of this year’s Lausitz Festival. The newly created word means enriching the self through the encounter with another. This deserves support, especially on the eve of the election in this matter and just a few weeks before the one in the second federal state involved, Brandenburg – with foreseeable gains for the AfD, which absolutizes the self and wants nothing to do with the other. However, the question remains to what extent what is foreign has become so understandable that it can enrich what is one’s own. Of course, somehow people also love in China, and that’s something we have in common. But who here understands without explanation how people loved in China in 1598? Art, like anything beautiful, requires work.

And who can understand it in China? Zhang Jun is an innovator who has even adapted Shakespeare’s “Julius Caesar” for the classical Chinese stage. In Oybin it was also audible to laypeople that the traditional instrumental line-up of bamboo flute, fretboard zither and percussion was supplemented at selected points by European harmonized recordings. Should this be blamed as falsification? But Monteverdi’s operas are no longer performed here using the stage equipment of the 17th century. The genre, if it is not just a museum, is changing, and at some point “otherself” also applies in one’s own country. If the evenings in Oybin encouraged us to take a closer look at the matter, they were worth the trip.

Become a member of the nd.Genossenschaft!

Since January 1, 2022, the »nd« will be published as an independent left-wing newspaper owned by the staff and readers. Be there and support media diversity and visible left-wing positions as a cooperative member. Fill out the membership form now.

More information on www.dasnd.de/genossenschaft

sbobet sbobet88 slot demo judi bola online