People have a hard time recognizing exponential growth.

Photo: Wikipedia

Since ancient times, people have tried to obtain information about impending good or bad luck. Traditional means of looking into the future were divine prophecies – conveyed by mostly human prophets and oracles. More mundane and still popular today are the services of astrologers and fortune tellers. However, if you want to go beyond good and bad luck in everyday life, it is better to use the tools of mathematics, which allow quite precise predictions in some areas and can at least explain why predictions fail in others.

The British mathematician Kit Yates deals with the art of making correct predictions and the many ways in which predictions can fail in his book “How to predict what no one expects”, which was recently published in German. The biggest hurdle is probably the human limitation in understanding certain everyday phenomena. The fact that most people have difficulty correctly assessing probabilities makes them susceptible to the tricks of fortune telling or fraudulent betting, whereas fortune tellers and betting kings must be very knowledgeable in this area.

The tendency to linear thinking

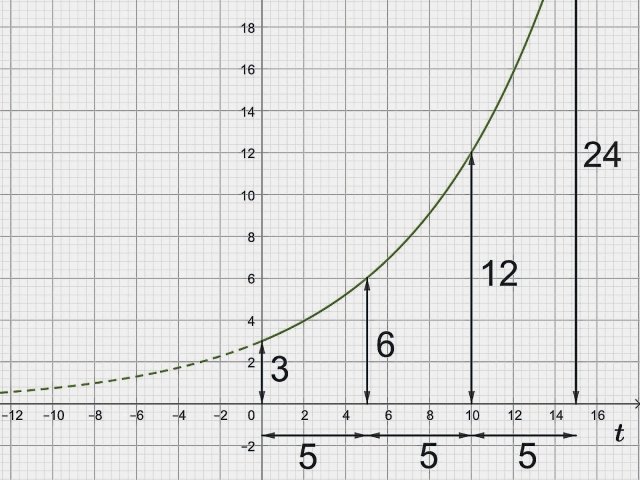

Most people are probably familiar with the problem of non-linearity from reporting on the corona pandemic. Growth that initially seemed linear suddenly turns out to be exponential with a steep upward curve. Initially low numbers of cases and associated deaths multiplied within just a few weeks. Most governments lagged behind in their response. This, as Yates explains, is due to the “exponential growth bias” to which human consciousness is subject. We tend to perceive growth as linear when in reality it is exponential. In the initial stage, the curves of both growth functions can hardly be distinguished.

What chance doesn’t teach

In addition to probability and nonlinearity, random patterns also cause problems for the human brain. For example, if you randomly distribute points in space, they are not evenly spaced from each other, but form clusters in places. This makes it tempting to read meanings out of the random patterns, especially when you stack several random distributions on top of each other. This is what happened, for example, with regard to leukemia in children and the distribution of high-voltage power lines, first by a group of parents in the USA, and later also by Swedish scientists.

Take feedback into account

Yates describes these and other problems of human perception that prevent us from having a clear view of the future. In addition, the forecast itself can change people’s behavior. Yates describes such feedback effects as “boomerangs,” supposed solutions that actually make the problem being addressed worse, or predictions “that change the future and destroy themselves.” Official health warnings – particularly those aimed at young people – can backfire. Studies from the USA and Great Britain showed that warning labels on cigarettes led to a significant increase in smoking among teenagers. Another, more complex example is dealing with the Covid-19 pandemic. Given the rapid increase in infections and deaths at the beginning of the pandemic, scientists warned of much higher numbers of deaths, which probably did not occur due to strict contact restrictions. This in turn caused the scientific forecasts to lose credibility among the public, made people less willing to reduce their contacts and allowed new waves of infections to spread.

Perhaps the greatest difficulty in forecasting is – and this is likely to be the case in the global climate system – that not just two but a large number of components interact with each other. But improvements are possible here too, as the history of weather forecasts shows. But the most important thing remains the willingness to learn from past mistakes and update your own opinion based on new data. Better mathematical understanding can help, and this book is worth reading.

Kit Yates: How to predict what no one expects. Piper, 432 pages, hardcover, €24.

Subscribe to the “nd”

Being left is complicated.

We keep track!

With our digital promotional subscription you can read all issues of »nd« digitally (nd.App or nd.Epaper) for little money at home or on the go.

Subscribe now!