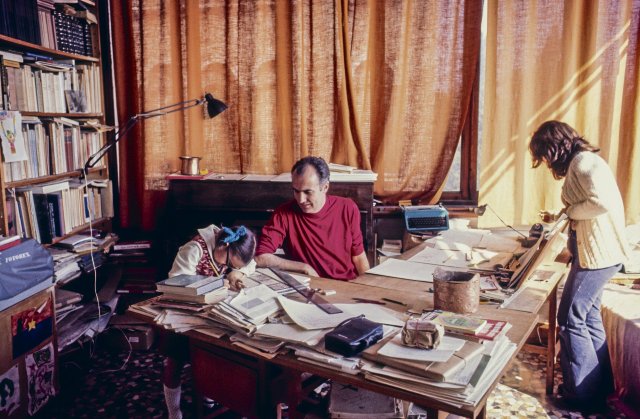

The woman sorts sheet music, the daughter practices writing – the composer Luigi Nono in his house, 1972

Foto: IMAGO/UIG

On the first day of the Venetian Carnival, thick fog lies over the lagoon. Tourists, dressed in the ugly masks that are sold on every corner, push their way through the streets, the squares are sprinkled with confetti. The motto of this year’s carnival is moderately original: “The extraordinary journey of Marco Polo.” Polo’s grave is said to have been in San Lorenzo, although this could never be verified. In the former monastery church in the Castello district, the composer Luigi Nono’s late major work “Prometeo” was played on the occasion of the 100th birthday of the composer; The four performances were literally stormed.

The fact that the “Prometeo” returned to the place of its premiere after 40 years would only be worth a footnote in other pieces – not in the “Tragedy of Hearing”, this large acoustic spatial production. Nono, for whom avant-garde and awareness of tradition did not form a contradiction, was, as a Venetian, influenced by the polychoral music that composers like Giovanni Gabrieli practiced in San Marco, and would also have liked to have conceived his “Prometeo” for St. Mark’s Basilica. The choice ultimately fell on the secularized church of San Lorenzo, which acquired its current appearance around 1600 and is characterized by a floor-to-ceiling altar that divides the square room into two parts: the lay people sat on one side and the Benedictine nuns on the other.

nd.DieWoche – our weekly newsletter

With our weekly newsletter nd.DieWoche look at the most important topics of the week and read them Highlights our Saturday edition on Friday. Get your free subscription here.

Carlo Fontana, who was then head of the Biennale’s music department, made a major effort in 1984 to use his entire budget for “Prometeo”, a co-production with La Scala in Milan; Claudio Abbado conducted and Renzo Piano designed a wooden “Barca” that connected the two parts of the church and in which the musicians, singers and speakers for the live electronics were positioned in galleries around the audience in order to achieve the spatial sound that Nono had in mind to generate. You were sitting, so to speak in a sound body.

Anyone who had hoped to experience the resurrection of Renzo Piano’s construction in San Lorenzo was, however, disappointed. The “Struttura” was used again in Milan in 1985, but was then sawn up and stored; it can no longer be used today. Now the musicians were spread out on simple scaffolding; Unlike in 1984, instead of the two interacting rooms of the “Barca” and the church surrounding it, a unified sound space was created.

Until just a few years ago, a performance of “Prometeo” would have been unthinkable without the participation of the SWR experimental studio in Freiburg. Its director Hans Peter Haller and later André Richard had still worked with Nono and adapted the live electronics to new performance locations. So that it doesn’t just remain an oral tradition, André Richard and Marco Mazzolini at Ricordi have edited a “Prometeo” score based on the second Milan version, which also makes the use of live electronics understandable.

Luigi Nono’s first two musical theater works, “Intolleranza 1960” and “Al gran sole carico d’amore”, premiered at La Scala in 1975, were initially controversial, and are now part of the repertoire; The time gap makes their roots in the Italian opera tradition clear today. These are combative pieces in which the convinced communist addresses the history of class struggle and revolutions.

Nono avoids the term opera and speaks of “Azione scenica”. He initially had a “scenic action” in mind when he set out to work on the Prometheus material based on the tragedy of Aeschylus. But then, while he was experimenting with live electronics in the Freiburg studio, he moved further and further away from the theater, and his “Prometheus” – the Titan who robs the gods of fire and is punished for it – mutated into an anti-opera: It There is no stage, no protagonists, not even a plot, just a purely “acoustic dramaturgy”, a sound stage on which the sounds move around the listeners.

As a “libretto,” Massimo Cacciari, the philosopher and later mayor of Venice, created a text collage that mixes Greek, German and Italian, goes from Hesiod to Friedrich Hölderlin to Walter Benjamin and comes across as somewhat educational. Of course, Nono’s treatment of the text is not suitable for guaranteeing even partial comprehensibility. For him the text is primarily material.

Nono and Cacciari conceived the nine-part, approximately 135-minute piece as an “archipelago” and therefore refer to individual sections as “isole”. Apart from striking outbursts, the dynamics are subdued; lying and floating flat tones, colored microtonally, shape the sound of the piece, which moves forward in a slow style. There are hardly any breaks, the vocal level is strongly influenced by sopranos singing in high registers – “bel canto” à la Nono. Unlike his early electronic pieces such as “La fabbricca illuminata,” in which he pits the human voice against the noises of the technical world, he avoids these contrasts in “Prometeo.” The sounds are reverberated, transposed, sent through the room with the halaphone invented in Freiburg, but not distorted to such an extent that everything cannot merge at any time.

With the separation from Freiburg, the time has finally come to question the “Prometeo” again. In Venice there were at least three musicians involved: the flautist Roberto Fabriciani, the trombonist and tuba player Giancarlo Schiaffini and the electronics player Alvise Vidolin, who had been there 40 years ago and guarantee a certain continuity. Marco Angius (with Filippo Perocco as co-conductor) led the Coro del Friuli Venezia Giulia and the Orchestra di Padova e del Veneto; Livia Rado, Rosaria Angotti, Chiara Osella, Katarzyna Otczyk and Marco Rencinai were the vocal soloists in the convincing ensemble. What was heard in San Lorenzo was a rather “loud” “Prometeo” that did not seem to want to take part in a pianissimo undercutting competition at the audibility limit, as was the case with André Richard. One could also get the impression that the greatest possible fusion of sound levels was not the primary goal.

“Suddenly I found myself completely under the spell of the necessity of hearing itself,” said Nono, describing his starting point in the early 1980s. Whether there was a turning point on the threshold of his late work that led away from the “political” Nono towards a new inwardness has been much discussed. Nono himself saw no break and spoke of wanting to broaden and deepen his thinking. The musicologist Matteo Nanni, who published a Nono book entitled “Politics of Hearing” in 2022, also emphasizes the continuities. The late Nono demanded an “active attitude” from the listeners that had to remain open to “plural truths”: “And these truths are not imposed by the music as abstract, supernatural axioms, but rather reveal themselves at the same time as they hide , in the materiality of the sound and its increasingly radical voids.«

Subscribe to the “nd”

Being left is complicated.

We keep track!

With our digital promotional subscription you can read all issues of »nd« digitally (nd.App or nd.Epaper) for little money at home or on the go.

Subscribe now!