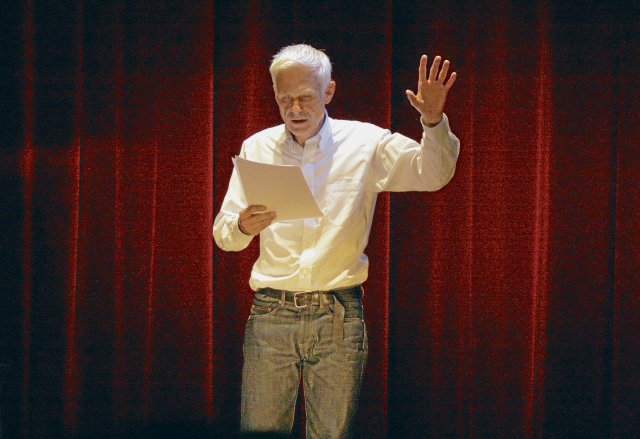

Novel at a distance: Rainald Goetz presents “Johann Holtrop” at the Deutsches Theater Berlin in 2012.

Foto: 360b/Alamy Stock Photo

Because everything, everything, everything concerns us.« In 1983, Rainald Goetz, at the age of 29, read out this maximalist permanent reception imperative, disguised as a statement, with a bleeding forehead in front of the camera in Klagenfurt am Wörthersee. In the end, the doctor of medicine, or more precisely a psychiatrist, derided by Wiglaf Droste as a “bleeder,” did not win the competition for the Bachmann Prize; But he had created the only literary television image with memorable value. A star was born. It was the beginning of one of the most productive and beautiful literary contemporaries.

In the same year, Goetz’s debut novel was published by his first and only publisher, Suhrkamp: “Irre,” the story of the psychiatrist Raspe, named after the RAF man, based on Goetz’s own experience in a Munich clinic. How the psychiatric system misleads the healer himself; How institutions do not serve to recover those under protection, but rather perpetuate their suffering because no one takes care of the other, but rather handles them, was written down here with a force that is unique in German-language literature. The language was Bible, Benn and Baader.

nd.DieWoche – our weekly newsletter

With our weekly newsletter nd.DieWoche look at the most important topics of the week and read them Highlights our Saturday edition on Friday. Get your free subscription here.

As a student at the time, Goetz was a reader of critical, Marxist theory, and absorbed as many thoughts, arguments, and truth-seeking writing methods as he could get behind his not-yet-scarred forehead. He enjoyed attending Karl Held’s lectures, but did not end up in any group, but instead transformed the apodictics of these writings into a strict but individual writing work in the service of truth and enlightenment. He also belonged to the circle of the more liberally inclined essayist Michaelrutschky, with whom he later broke up, but whose often bitter docility certainly helped the young Goetz not to perceive society exclusively in prefabricated categories that are (rhetorically) committed to its liberation. And then there was punk and the way of life “We drink until there is blood.”

This was followed by the dark RAF fantasy “Controlled”, the report collection “Kronos”, texts for the theater, where Goetz is considered a prime example of post-dramatic pieces, although early influences were the magical-anarchic Bavarian universal artist Herbert Achternbusch and the socially critical writer Franz Xaver Kroetz, so that his early stage work does not indulge in meta-play, but rather aims to attack German conditions.

As is well known, the 90s changed almost everything. Goetz moved from Munich to Berlin, to Wedding, with a view of the Charité, and gave himself up to the rave and reading Niklas Luhmann: Still wanting to understand everything, but not having to move anything because everyone is marching in the Love Parade. Those inclined to hedonism, at least among young students, have his story “Rave” at home; The internet diary at the turn of the millennium, “Waste for All,” turned a year’s worth of notes into another fat block of book. Goetz became friends with the techno DJs Westbam and Sven Väth, stood around in clubs, noted the new language of fun in the dark, discovered Ecstacy and let the negativity of the early years rest.

Life was cheerful in the jungle of discourse. The fact that the media mania is tearing at the psyche and that professional cool people hardly care about society still resonates without morality. Goetz didn’t see what was going on in the East. He had nothing interesting to say about the GDR. But Goetz was able to dismantle the poisoned gift of the market economy – after exploring the political press sphere, including Springer, which the Berlin Republic maintains – in a brilliant book.

The (suicidal) world of higher management, the hamster wheel of everyday working life in blind greed for profit, was then the subject of his only novel at a distance in 2012, with characters, without Goetz’s first-person views: »Johann Holtrop. Demolition of Society” explores the souls who try to keep middle classes and larger capital going in this country. Some of this takes place in industrial parks in East Germany. And other places that should be replaceable in case of doubt.

Then there was another break from work. The Büchner Prize was awarded in 2015. We remain silent about the Federal Cross of Merit. Most recently there were two pieces, “Empire of Death” (2021) and “Baracke” (2023), which took on political complexes that were too broad to create any urgency. The criticism remained mild.

Rainald Goetz is a projection surface for quite a few of his fans – probably mostly white men – so that people like to make prophetic demands on him. Even if it is rumored that he now regularly goes to the (Catholic) church, this expectation of salvation through writing is cheap – even if Goetz can think in writing about writing directed towards the world in an incomparably invigorating way. He remains one of the best contemporary writers of the last 40 years. Anyone who reads his texts at the right time, young and melancholic or a little older but not completely frustrated, will be gifted with an energy that has both criticism and love for this world.

Rainald Gotz turns 70 on Friday. Thank you for everything!

Subscribe to the “nd”

Being left is complicated.

We keep track!

With our digital promotional subscription you can read all issues of »nd« digitally (nd.App or nd.Epaper) for little money at home or on the go.

Subscribe now!

judi bola sbobet88 judi bola online sbobet