Who was the man with the hedgehog face?

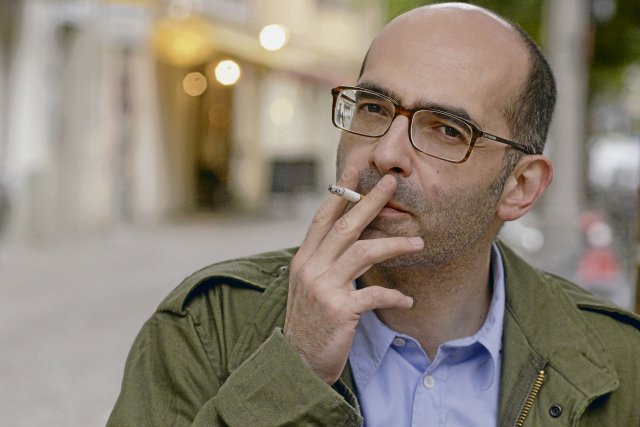

Photo: image/set

For a moment it was like before. Maxim Biller had pronounced what nobody wanted to hear in the end of June in a “time” column. This time that in his view, Israel has no other choice in the war against Hamas and that the role of the bogeyman is preferable to a military defeat. Of course everyone howling. The editorial team of the “time” was most awkward; First the column appeared in the printed “time” and then it disappeared from “Zeit” online.

But it quickly became aware that “everyone” has not existed for a long time. Over the age of 40, Maxim Biller has described a trailer community that is not only enthusiastic about his pilgrimages. His novels and stories are now part of the canon of contemporary literature. And what would be better documented than that the literary magazine “Text+Critique” is dedicated to him 248.

Maxim Biller’s novella “The Immortal Weil” is not impressed to put teenagers in ecstasy.

It was a long way to get there. That leaves no doubt about that who write about him. Claudius Seidl, former feature chief of the “Frankfurter Allgemeine Sonntagszeitung”, recalls the The Maxim Biller’s first -time “if I was rich and dead” in the early 1990s. In it he recognizes “the amazing continuity of a literary hostility to Jews”, which Heinrich Heine felt in the 19th century.

And Mara Delius puts the rhetorical question in her essay “Attempts about the disturbant or why Maxim Biller must not be a German critic”: “Is the reason why Biller is a Jew? (…) A Jewish writer who does not let the Germans be German in peace and is always only read by them as a Jewish writer? ”Is it worth trying out the test. Because at the center of his current amendment is also a Jew, the Czech writer Jiří Weil.

“Novella”? Something rings! Curious of which teaching sentences from school days have made their way into the long -term memory: “The amendment is about an outrageous event.” I can only explain that the sentence is stuck in the consciousness in such a way that I by no means found the events described in German lessons, but rather as a stinking. The teacher, who succeeds in enthusiastic about students of the 19th century, still has to be invented.

Maxim Biller’s novella “The Immortal Weil” is also not taken with it to put teenagers in ecstasy. The almost 60 pages are about how someone (now deeply breathe deeply) goes on the way home after work. The “outrageous” is not the sites that the stroller and bus traveling happens, but the memories that they cause.

Maxim Biller is once again concerned with that bestial 20th century that has produced fascism and Stalinism human -minded ideologies. What these worldviews – with all differences – combines: the individual counts nothing; It is only a disposal that can be sacrificed for “the big thing”.

The writer Jiří Weil (1900–1959), who operates in the book under the nickname “Jirka”, of course, has bad cards. As a Jew, he is on the Nazis death list per se. But he is also a thorn in the side of the Stalinists because his novel “Moscow – the border” is not suitable as a revolutionary propaganda, but exposes it as a “philistine”, “reactionary” and “parasite”, which is “the weed that you have to tear out on the stony path”. To make matters worse, he is also suspected of having participated in the murder of the Leningrad party secretary Sergej Mironowitsch Kirow – a guilty verdict would have meant the safe death.

Jiří because survived. Nevertheless, he is not suitable for the triumphant. On the one hand, because on April 1956, on which Maxim Biller looks into his head, he already knows that he is terminally ill. On the other hand, because the temporary victories about the death of painful defeats are accompanied in life. He suffers from the fact that he was “wiped out twice as a writer and is therefore only allowed to dig like a half -blind flourworm through the dust -covered shelves and camp of the Jewish Museum.”

The first paragraph of the book makes it clear that we are not dealing with any lucky child: »Who was the man with the hanging hedgehog face (…), who had left the office of the Jewish Museum (…) every day for many years and shortly afterwards slowly went up Paris Strasse to Moldau? And why did everyone who saw him immediately sad? “

The answer was revoked by Biller two pages later: “I have always been punished for the fact that I could not be as confident.” The others, for example, is the writer Julius Fučík murdered by the Nazis, who “spoke and wrote for millions, not like me, the self -loving, lonely petty bourgeois”. The convinced Stalinist Fučík accuses Weil that he had revealed our cause with his “hastily Moscow report (…).

But there is also the Czechoslovak Minister of Culture Ladislav Štoll, who is introduced as a “friend” before the image of “loved, weak and dishonest Ladislav” is noticeably. “The uneducated son of an innkeeper”, a “Feistes Wirtshauskind”, turns out to be a careerist and opportunist, who at a session of the writer’s association delivers to the knife and justifies himself with the words: “Be bad, Jirka, I had to sacrifice someone before you notice that I don’t notice any word anymore.”

And suddenly one understands why real socialism in 1989 collapsed like a soufflé. There were too many Ladislavs, too many followers who would have found their way up in any other political system.

But you understand even more, and that has nothing to do with fascism and Stalinism of the 20th century. This world has always been shaped by conviction such as Julius Fučík and opportunists such as Ladislav Štoll, that is, people who are “confident” and never come up with the idea of questioning their thinking and doing. Some of them can be met as statues later, because: “Only those who have power over other people will become stone.”

A skeptic and hesitation like Jiří Weil, on the other hand, only has the letter: »I am a writer, that’s very simple. As if you are right -handed or left -handed, this is nothing more. (…) Anyone who says that the world can be changed with words does not understand anything about words. You can only tell about how beautiful everything is, even if it is terrible. “

At this point at the latest you understand why Maxim Biller can put himself in the anti -hero of his novella so well. Because even Biller has been doing nothing other than because: He describes a world that urgently needs change since his “hundred lines of hate” columns in the magazine “Tempo”. It may be that as a Jew who already felt anti -Semitism as a child (“I experienced a lot of silent racism in Germany in the 70s and 80s”), but has a finer sensor than the descendants of the “men’s breed”. However, it does not fit into the drawer “Jewish writer”. The fact that his novels and stories have now been translated into 19 different languages shows that Maxim Biller describes universal human experiences. Has anyone called “world literature”?

Maxim Biller: The Immortal Weil. Edition 5plus, 72 pages, 18 €. Only available from the 5plus bookstores (5plus.org).

Text+criticism, issue 248 – Maxim Biller. Edition text + criticism, 102 p., 28 €.