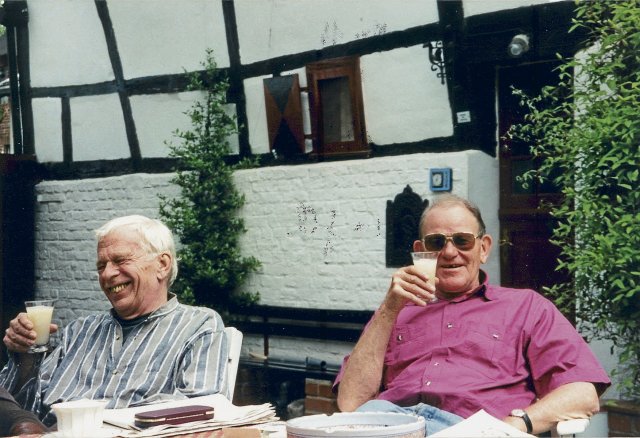

Conversations about Walter Ulbricht and other socialisms: Peter Hacks visits André Müller Sr. in Juntersdorf, North Rhine-Westphalia, at the end of the 90s

Photo: Eulenspiegel (2)

Peter Hacks, the playwright, poet, children’s book author and essayist, wears silk underwear. The rumor was spread at the beginning of the 1980s by people from the circle of the playwright Heiner Müller, whom Hacks had helped out with money, spirits and patronage two decades earlier. It was intended to brand the most frequently performed German playwright at the time as a snob. Anyone who was not involved in the Berlin art elite gossip back then will now find out from the finally available correspondence between Hacks and his lifelong friend André Müller Sr. from 1957 onwards. It provokes a grin.

Hacks called me once in 1995 to ask for advice. The Hamburg Edition Nautilus has just published the volume “The Stories”, his first book in this publishing house, which otherwise focuses on the literature of anarchists. And Hacks wanted to know where the best place to hold a press conference for this premiere was. Hacksologically uninformed, I suggested to him the still existing International Press Center on Berlin’s Mohrenstrasse, known to all journalists, equipped with the necessary technology and quickly accessible from most editorial offices in Germany’s largest city. That was all well and good, replied the poet, but “not snobbish enough” for him. Whether I don’t know anything else. I thought of the “Medici” restaurant that existed in Kreuzberg at the time. He immediately liked the proximity to the dynasty of Florentine Renaissance aristocrats. I don’t know if he looked around the place. His press conference then took place in Weimar, in Goethe’s neighborhood. But it was said that hardly any journalists got lost in the “Elephant” hotel.

The communist Peter Hacks, who came to the GDR from the West in 1955 and was a cheerful and polite man, was, in my opinion, no snob, but he valued the reputation of being one. His attitude of aristocratic superiority was justified by his intellectual rank, his overwhelming education, and his world-famous work. It intimidated the opponents that the GDR’s greatest playwright, who was at times the most banned playwright with his plays “The Worries and the Power” and “Moritz Tassow” but in the long run was the most loyal to socialism, found in his increasingly fundamentally dissident colleagues. And as the correspondence also shows, she helped him to maintain his composure in the darkness of defeat.

But actual arrogance towards fellow human beings looks different than Hacks, who at his country estate in Brandenburg, together with his wife Anna Elisabeth Wiede, had lunch every day with his domestic servants, which he could afford and well because of his income, which at times was enormous by GDR standards paid. The poet was a political enemy of egalitarianism. He thought of socialism, which was also defended in its real form, as a meritocratic society, i.e. with necessary differences.

He saw the GDR on the way there in the era of Walter Ulbricht, who, after the construction of the Wall in 1961, introduced cautious and clever reforms, installed his market-oriented New Economic System and flanked this with a more liberal youth and cultural policy. For Hacks, Ulbricht was the enlightened ruler in a system of “socialist absolutism” who set out to balance the differences between the new “socialist classes”, the official apparatus and the intelligentsia. Ulbricht’s realistic view of socialism as a long-lasting, relatively independent social period made the SED leader a classic for hacks. Communism thus became for the poet an ideal that was only approximately achievable, namely of wealth and not of asceticism.

We no longer need to explore what the exchange with André Müller, the communist from Cologne, who himself wrote novels, stories and plays, but especially indispensable Marxist interpretations of Shakespeare, meant for Hacks’ becoming and work and how this was reflected in that. Ronald Weber did it in his excellent biography (“Peter Hacks. Life and Work”, Berlin 2018). She likes both Müller’s »Conversations with Hacks. 1963 to 2003″ (Berlin 2008) as well as the correspondence in this volume reviewed by Weber.

The correspondence between the two also confirms: Müller was Hack’s main advisor on all questions relating to the poet’s craft and at the same time a congenial partner in Kremlin astrological prophecies, which were often wrong. The Rhinelander, who had a temporary second home in the east of Berlin, served the GDR poet not only as an Eckerman, but also as a Neckermann, for example as a procurer of flower bulbs and original French Gitanes cigarettes, because Hacks didn’t like the ones from the German trade.

Surprises still arise. One is Hacks’ search for contact with Sebastian Haffner, the journalist and author who caused a stir not only with his “Comments on Hitler” but also with his description of the betrayal of the SPD leadership in the November revolution of 1918. Hacks asks Müller repeatedly asks him to get Haffner’s address (whom he later visits in West Berlin) and becomes annoyed when Müller shows himself to be unable (or unwilling?) to comply. The reason for Hacks’ interest is the essay “Germany Between the Superpowers,” from which he draws the following conclusion: “We all knew that the Muscovites intended to market the GDR several times, but I think we all overlooked that their inclination to do so is fundamental.”

Written at the end of 1986, it speaks of forebodings of what could come to the world, even if Hacks still believes the new Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev’s promise not to “offer the GDR for sale at the moment.” That should change soon. One might consider Hacks’ “secret service snooping”, which could actually take on bizarre features, like Ronald Weber, to be the poet’s “standing folly”, but it still led him on the right track.

A BND dossier that came to light in 1993 put on record the false game that the Kremlin was playing with its “brother country,” the GDR. It provided information about a Soviet secret service structure called “Lutsch”, which recruited people in the GDR apparatus, in culture and science for Gorbachevist activities (see “Moscow and the ‘turnaround’ in the GDR”, ND, September 24, 1993). The fact that the GDR itself was in a miserable state cannot be blamed on Hacks, who criticized Honecker’s illusion-driven regime with his considerable artistic resources in front of a large audience.

The second, if not equally surprising, discovery: Hacks made a forever quotable declaration of honor for Wolfgang Harich, the philosopher and literary scholar who was considered a ragamuffin by the GDR dissidents fueled by Walter Janka, Stefan Heym and Stephan Hermlin. The reason for this was the refusal of the DKP magazine “Kultur & Gesellschaft”, co-edited by André Müller, to print Harich’s violent essay against a Nietzsche renaissance in 1987 (which later appeared in a somewhat mutilated form in “Sinn und Form”). Hacks criticized the rejection: “It would certainly have been a process: a great text by a great man of honor about a great villain; The usability in detail would hardly matter any more.”

As already mentioned, we read correspondence out of a retrospective interest in gossip. So if you want to know what Hacks thought of friends, enemies, acquaintances and this or that political figure, you will get your money’s worth in this excellently written volume. Appearances include: Sahra Wagenknecht, whom he supported with spirit and money, Eberhard Esche, whose wife he occasionally cheated on, and Wiglaf Droste, whose “Schlachtenbummler” columns in 1992/93, I can attest, in the newspaper “Neues Germany,” he read, including Vladimir Putin, about whom he was wrong, initially considering him to be just as incompetent as Gorbachev.

Peter Hacks/André Müller Sr.: The correspondence 1957–2003. Ed. Heinz Hamm and Kai Köhler, Eulenspiegel-Verlag, 1280 pages, hardcover, €58.

Become a member of the nd.Genossenschaft!

Since January 1, 2022, the »nd« will be published as an independent left-wing newspaper owned by the staff and readers. Be there and support media diversity and visible left-wing positions as a cooperative member. Fill out the membership form now.

More information on www.dasnd.de/genossenschaft