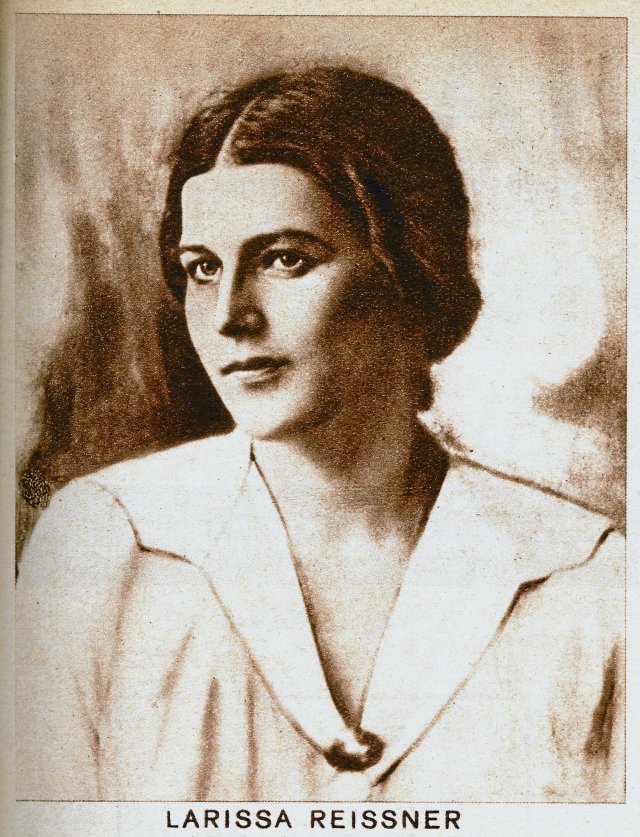

Larissa Reissner in a photograph published in “AIZ” in 1931

Photo: Collection Jonas Kharbine Tapabor

The Volga, the mighty and often sung Volga, flows majestically over everything as if nothing had ever happened. I’ve been to her three times, most recently in 2018. I had moved into accommodation in Zelenodolsk, 30 kilometers from Kazan, and I often sat at an inconspicuous ferry dock, right next to an imposing railway bridge that constantly allowed the heavy Russian trains to pass overhead , from north to south and vice versa. Of course I took the ferry to opposite, from whose small train station Sviyazhsk Leon Trotsky once commanded the great Kazan operation in his famous armored train and at the same time launched the Red Army with volunteers. The battle for “my” bridge, which was important in the civil war and initially almost hopeless, lasted four weeks in the summer of 1918 and ended victoriously.

Exactly 100 years later, I was still here completely unaware of the historical significance of this now peaceful place. I had no idea that the legendary revolutionary Larissa Reissner also fought here, intelligent and courageous, almost daring. It was only through their cunning reconnaissance in the hinterland that they managed to reunite the two destroyed parts of the 5th Army and also regain control of the Volga. She was the first female commissar of the Red Army and her skills were valued beyond measure. Soon after my last trip to Russia, my friend, the historian Werner Abel, gave me a book bound in dark red linen with the title “October” embossed in gold letters. It includes almost all of Larissa Reissner’s volumes, 1926, after her death, edited by Karl Radek, her last partner. Since then I have known more about Larissa Reissner and about “my” bridge”. That’s not enough. Recently, my friend, coming from the book fair, gave me the latest book by Steffen Kopetzky: “Damenopfer”. It’s called a novel, but it’s more of a biography that meticulously captures the entire Reissner cosmos, as far as the current archive situation allows. Both books were good for me.

Larissa Reissner, born in Lublin in 1895, came from a highly educated family of Bolshevik professors who had to emigrate to Germany in 1903. Larissa attended school in Berlin, met August Bebel and Karl Liebknecht and Lenin’s letters to her father in her parents’ home. The family lived in Russia again in 1907. Larissa wrote poems, plays and articles and, as a student, even published a magazine called “Rudin” directed against the impending war. She also published work in Gorky’s magazines. She loved literature and at times some poets, such as Nikolai Gumilyov. Before and during October 1917 she became politicized and looked after sailors who wrote in Kronstadt. Here she fell in love with the lieutenant of the Baltic Fleet Raskolnikov and married him. Immediately after the outbreak of the civil war in 1918, both went to the front, he as commander of the Volga flotilla, she as commissar, and fought victoriously over the Whites and the English occupiers, from the already mentioned Kazan operation across the entire Volga to the Caspian Sea Persia.

All of this is excitingly described in her book “The Front 1918–1919”. In the chapter “Sviyazhsk” she writes: “None of the demobilized old Red Army soldiers, the founder of the Workers ‘and Peasants’ Army, will, when they come home and think back to the three years of civil war, forget this fairy-tale epic near Sviyazhsk, from where they started on all four sides, the waves of revolutionary attacks began to move. In the east – to the Urals, in the south – to the Caspian Sea, the Caucasus and the Persian borders, in the north – to Arkhangelsk and Poland. Of course, all of this didn’t happen all at once, not at the same time, but it was only after Sviyazhsk and Kazan that the Red Army crystallized…”

Throughout her life she wrote and published reports from Afghanistan, where she served as Ambassador Raskolnikov’s wife from 1921 to 1923, often from Germany, primarily from the time of the failed departures in 1923 and 1924, and she traveled again and again, also out of dissatisfaction with the NÖP , to the Russian workers, to the factories and mines of the Urals and Donbass, or to the Polish-Russian peace negotiations in Riga in 1921. Larissa Reissner, and this is wonderfully described by Kopetzky, was also a Comintern agent. Despite the German defeats, it adhered to the idea of ”permanent revolution” and therefore – very independently – established international contacts for a future world free of exploitation. Sometimes she sacrificed her “queen” in a cool, calculated manner in order to drive the king into a corner on the next move. Yes, she acted analytically, always keeping the essential goal in mind.

Despite their charm and desirability, personal happiness should not be permanent. At the age of 30, in February 1926, she died of typhus. Her funeral became an event. There came Trotsky and Radek, Tukhachevsky and the Kollontai, countless poets like Pasternak and Babel and Pilnjak, many actors and of course sailors and officers from their time together in the victorious Volga Flotilla. She gave constant help to quite a few people in distress, brought food to Mandelstam and Akhmatova, and wrote encouraging letters and the strongest defenses for the implementation of books. Her uncompromising and incorruptible voice against corruption and sycophancy was now missed. Only through death was she able to escape Stalin’s terror, unlike almost all of her friends.

Boris Pasternak dedicated the thoughtful poem “Larissa Reissner in Memory” to her and recited it at the grave. Leon Trotsky also spoke. His words are recorded in his autobiography “My Life”: “This magnificent young woman who charmed so many passed like a fiery meteor in the sky of the revolution. With the appearance of an Olympian goddess, she combined a fine ironic mind and the bravery of a warrior… In just a few years she grew into a first-class writer. Passing unscathed through fire and water, this Pallas of the Revolution suddenly burned to death from typhus… All of us who stand at her grave today are stunned by this loss for the international workers’ movement and the world revolution.

Under “my” imposing railway bridge, the Volga flows sublimely and silently, as if nothing had ever happened.

Steffen Kopetzky: Queen sacrifice. Rowohlt,

443 p., hardcover, €26.

Become a member of the nd.Genossenschaft!

Since January 1, 2022, the »nd« will be published as an independent left-wing newspaper owned by the staff and readers. Be there and support media diversity and visible left-wing positions as a cooperative member. Fill out the membership application now.

More information on www.dasnd.de/genossenschaft