The Johann-Strauss monument in the Vienna City Park is a popular motif for selfies. For the 200th birthday of the Waltz king, Vienna dedicates his own festival year.

Photo: Imago/Lem

At the opera ring, Fiaker hold in front of the magnificent Renaissance facade of the Vienna State Opera. Young men in historical clothing with white powdered wig, red tailcoat and golden vest offer concert tickets for the evening. Passers -by stop, pull out their cell phones for a selfie. A musician bowed between the hustle and bustle, lifts the violin, and the bow slides over the strings. The first bars float through the air and fight with urban noise. “At The Beautiful Blue Danube”. In the anniversary year of Johann Strauss, which was born on October 25, 1825, in the anniversary year, which was born almost 200 years ago.

Ilse Heigth is a proven Strauss expert, author and city guide. I am in Vienna with her – in the footsteps of the Waltz king, in the places where he once lived, played, played and married. “The State Opera, opened in 1869, is of course the first house on the pitch – but for Strauss it is also a symbol of a certain contradiction.” Because operetta was once frowned upon. It is only allowed in New Year’s Eve once a year. And then? Of course “the bat”. “A feel-good piece,” says the expert, “funny, frivolous”, and if it is sad, “then funny and sad”.

Johann Strauss was already a superstar in his time. Incidentally, his famous father, also a composer, wore the same name. But no other music stands for Vienna as that of Strauss Junior. Not only did he compose within the family dynasty: there was bitter competition between him and his father. In the end, son Johann was more successful than his also talented brothers – and as Strauss senior. He wrote over 500 works: waltz, polkas, marches, quadrilles, gallops – and of course operettas.

It continues with the BIM, as the Viennese lovingly call their tram. It squeaks around the curve to the next station: the theater at Vienna. Heigth points to the neoclassical building. “Almost all of the Strauss operettas were premiered here,” she says. “And he conducted himself – often with the violin in his hand.”

The beautiful schani

We stand on the sidewalk, through a window penetrates quiet sample. “He was a highly talented conductor,” says the city guide. He was known for his own style: he wore a small -scale trousers, a black tailcoat, a white vest and a necklace. His movements were body -emphasized when conducting. “He was a beautiful man”, Ilse Heigth is sure. At that time, people called him “the beautiful schani”. Today he would probably be influencer or TikK-Star.

From the imposing theater, the path leads us to the “House of Strauss” – a multimedia experience museum about the history of the Strauss family, in the former Casino Zögernitz. Concerts still take place in the historic Strauss hall today. And here we have an appointment with a relative of the family: Eduard Strauss unfolds a sheet of paper with a family tree. “Johann Strauss (son) is my great -grandnail – once around the corner,” he explains. With his upper lip beard and the striking facial features, you might think that Johann Strauss would be personally opposed.

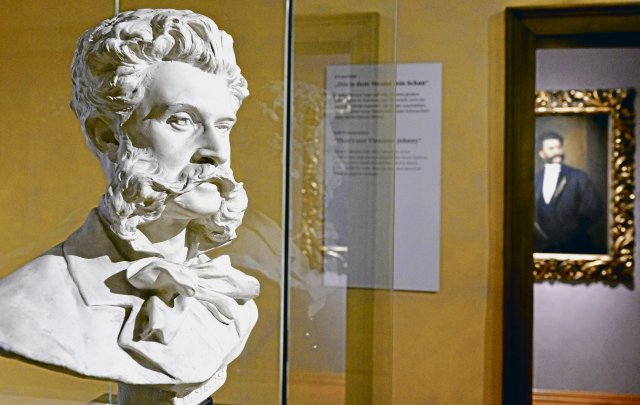

A bust of Johann Strauss in the apartment on Praterstrasse in Vienna.

Photo: Picture Alliance/APA/Hans Klaus Techt

Eduard Strauss leads through the colorful multimedia experience museum. There is not a single original object, but LED walls, sound installations, animated projections that inform about the history of the family-for example, about the repressed Strauss reception during the Nazi era. The Nazi regime stylized the waltz king to the German cult figure-and fell through its Jewish roots through falsification of documents. “Goebbels said: We cannot do that, we cannot ban the ostriches – Hitler liked it so much. And then you just arose, «explains Eduard Strauss.

Johann Straus’s son’s grandmother was Jew. The composer was “washed in” without further ado, his origin was repaid out of the files. Eduard Strauss shows the clumsy fake of his baptismal book by the “Reichszippenamt”.

The museum is an audiovisual homage to the whole family of Strauss. Johann, Josef, Eduard – musical brothers, from the featureletion of her time mocked as “Jean, Peppi and Edi”. Swaves like Boygroup members-only with cylinder instead of sneakers.

I ask him if his great -grandnail was a wealthy man. “Oh yes,” he is sure. “The operettas made him rich. There were royalties, and from every operetta you could extract waltzes and resell. Multiple recycling! ”So Johann Strauss was not only a brilliant composer, but also a clever businessman.

Love and scandal

Strauss kept moving to Karlsplatz – a place that is not a classic place at all, but a spacious park: with meadows, fountains and art installations. The subway and tram lines, bike paths and tourist flows cross here- a mixture of everyday chaos and great opera. In the shadow of the baroque dome of the Karlskirche, a particularly romantic chapter took place for Strauss, reports Ilse Hegerth. »Strauss married here. He was under the hood three times. It wasn’t that easy in Catholic Austria. “

Strauss’ first woman, Henriette “Jetti” Treffz, an opera singer who was older than him, married him with a big pomp. His third wedding, on the other hand, was a small scandal. “Strauss has had to change his citizenship and religion, became a Protestant and citizens of Saxony-Coburg and Gotha-the Viennese still take it a bit bad to this day,” says Ilse half seriously.

What do you not do for love: Strauss was engaged thirteen times. Adele German, his last wife, managed him until his death in 1899. Then she took care of his estate. The musician had no children with any of his women. But his curls were a coveted asset among his female fans.

»There is more fracture in this music than harmony› The bat ‹is not only frivolous – it is also socially critical, anarchic. And I want to show that. “

Roland Geyer Artistic director of the Strauss anniversary in Vienna

Heigth tells a story that is typical of the composer’s vanity: he dyed his hair and liked to distribute hair curls to female fans – until his wife noticed nobility and was worried that he would soon get a bald head. So she led black poodles for a walk and cut out a few hair tufts. Therefore, the Strauss curls came from then on.

Not far from Karlsplatz, Roland Geyer sits in his office. The cultural manager and theater director is the artistic managing director for the anniversary program “Johann Strauss 2025 Vienna”, that intends to break up the composer’s image. “I don’t want a UM-TA-TA Walkitsch,” he says. “But show how modern and contradictory this man was.”

The schedule comprises over 65 productions at almost 70 locations – opera, dance, performance, installations. Strauss should be heard and visible in all 23 districts of Vienna. Because Geyer has doubts how much people really know about Strauss. “Go onto the street and ask for a second work-many then wrongly say the Radetzky march. But he’s from his father. “

Strauss was pop, but also political. The Danube Walzer was created in 1866 and was premiered in 1867 – shortly after the Battle of Königgrätz, which lost Austria against Prussia. The original text is not about blue Danube, but of human suffering. “There is more break than harmony in this music,” sums up Geyer. »› The bat ‹is not only frivolous – it is also socially critical, anarchic. And I want to show that. “

“Think of Strauss re -thinking”

Strauss to think again – for Geyer, that also means: away with only big names, but courageous cross -genre experiments, installations and art to touch. For example with an escaper room by the Viennese artist Deborah Sengl. Your access to the composer is a very personal one – she is looking for breaks and hidden facets behind the shine. “In the shadow of doubt”, your walk -in puzzle game is called – an associative way of dealing with the work of the anniversary.

Visitors have to puzzle through lovingly designed rooms in the museum district. In the middle of puzzles, mirror surfaces and wall quotes, discover a bouquet that is more torn than its image. “He was a genius, of course,” says Sengl. “But also a person who was under pressure to have to deliver constantly.” The rooms are associative. You press buttons, open drawers, find letters, sketches, set pieces of a biography. Nothing is clear – everything is ambiguous. Here you do not meet the golden strauses, but the doubtful, the exhausted, the not perfect artist and people. “For me this is the more exciting strauses,” emphasizes Sengl.

You also come across the legacy of Strauss in the Vienna City Park. A saxophone player blows “Viennese blood” into the moist summer air. We follow the sound over winding paths, past sticks, joggers and a bus load of Asian tourists who want to go to a specific place. A apparently golden figure flashes between plane trees. The statue of Johann Strauss is the most photographed monument to Vienna – and a selfie for the digital sofa show at home. The composer is framed by dancing river nixes, which – depending on the perspective – embody the magic, but also the temptations of the Danube.

A scene like from an operetta: a bit transfiguring, a bit frivolous like the waltz: a dance that allowed men and women physical closeness, on the open stage – at that time in the 19th century. “Strauss was a revolutionary with a rhythm,” explains Heigth. “The waltz was previously considered offensive because men and women had to touch.” The dance was originally a scandal. And at the same time he had social explosive power: closeness that was not intended in the 19th century.