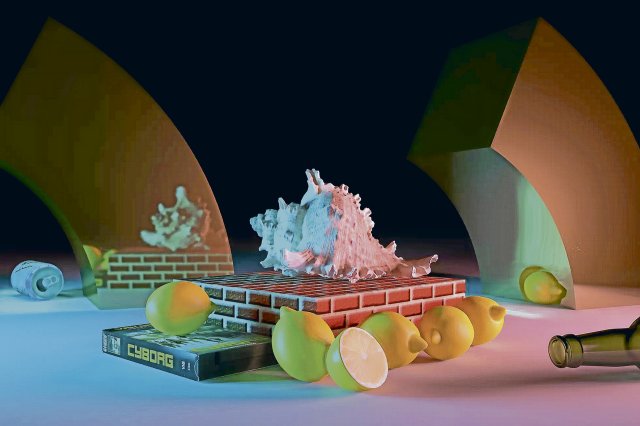

“Cyborg” by Takeshi Murata from 2011.

Foto: Takeshi Murata

There’s something wrong with the lemons. Their shells shine flawlessly yellow and promise tangy vitamin enjoyment. But who distributed the fruit so unnaturally in front of the surreally illuminated brick podium? And why is there an old VHS cassette next to it? “Cyborg” is the name of the work by the US artist Takeshi Murata from 2011. The eerily deserted scene was created entirely on the computer. However, Murata falls short of what was already possible in the year it was created. Graphically, the composition is more on the level of 90s icons like “Super Mario” or “Toy Story”. The final, deceptive touch of the reality simulation is missing. The lemons are too smooth, too round, too close to the ovaloid basic shape of the fruit. Why exactly this design?

Jacob Birken thinks he knows the answer. The art and media scientist takes Murata’s citrus haunting as the starting point for an analytical long essay about digital culture and its image practice. Under the title “On Pixel Realism,” the Cologne university lecturer goes back to the early modern era in order to debunk several innovation myths about artificial intelligence. Murata’s reference to the 17th-century Dutch still life, whose most popular props include lemons, is the focus of Birken’s argument.

First of all, he explains the technical basis. Murata uses processes such as 3D rendering, which is used in product design as well as in the entertainment industry. After first creating a virtual spatial environment, the artist adds banal objects like lemons. He either buys them as prefabricated 3D scans on so-called rendering platforms or has them generated on the computer by AI providers.

All of this sounds nerdy, contemporary and in the middle of the 21st century. Nevertheless, the creative method differs less radically from past eras than one might initially assume. What is known today as virtual reality was trompe l’oeil, the illusion of the eye, in the early modern period. Naturalistic accuracy, perspective and shadows were intended to tempt viewers to reach for painted grapes, pears or lemons.

Even in Rembrandt’s time, art worked with templates. Birken is reminiscent of Willem Claeszoon Heda, one of the most prolific still life producers of his generation. He used the study of the same glass jug for at least five different paintings. This is what Birken calls “media-immanent realism” – images are made from images. This concept of imitation, which no longer necessarily arises from contact with everyday physical reality, takes on a life of its own with electronic imaging. Examples of this are applications such as Dall-E or Midjourney, which generate images via text input. If I ask about a lemon, the software searches through everything that has to do with the keyword. I end up with the lowest common denominator of a lemon. The product of this “statistical rendering,” as some call it, comes from a mimetic intermediate realm: the representation is neither abstract in the emphatic sense of modernity, nor is it the classic representational mimesis of an identifiable template. The lemons in Murata’s still lifes are pure thing-ghosts, not imitations of an original.

The almost 140-page booklet cleverly brings together humanities and technical perspectives, although readers would have liked a few more illustrations. Some theoretical considerations are also not as new as the author sometimes suggests. After all, the discomfort with the reproduced world begins with Plato at the latest and not with Murata or the science fiction film “The Matrix”. Nevertheless, Birken scores points with its clear explanations and also takes into account the hidden materialism of the hyper-realistic image culture: Even the still lifes in the houses of the Amsterdam propertied bourgeoisie tell us nothing about the precarious situation of the maids who were busy preparing the painted treasures. Contemporary computer games or streaming series go far beyond the illusion of historical fine painting in the realism effect of their dragons and jungles – but this digital hyperrealism also conceals social reality all the more radically. The entire global information society is based on capitalist-neocolonial exploitation. Because, says Birken, “no one can afford the Play Station from the wages in the coltan or cobalt mines in the Congo, which could not be manufactured without these raw materials.” This is where the critical potential of positions like Murata’s lies: the calculated irritations in digital illusionism want to make you suspicious and offer breaks through which you can look out of the digital cave.

Jacob Birken: On pixel realism. Takeshi Murata’s still life “Cyborg”. Loops Verlag, 140 pages, br., €22.50.

#ndstays – Get active and order a promotional package

Regardless of whether it is pubs, cafés, festivals or other meeting places – we want to become more visible and reach everyone who values independent journalism with an attitude. We have put together a campaign package with stickers, flyers, posters and buttons that you can use to get active and support your newspaper.

To the promotional package