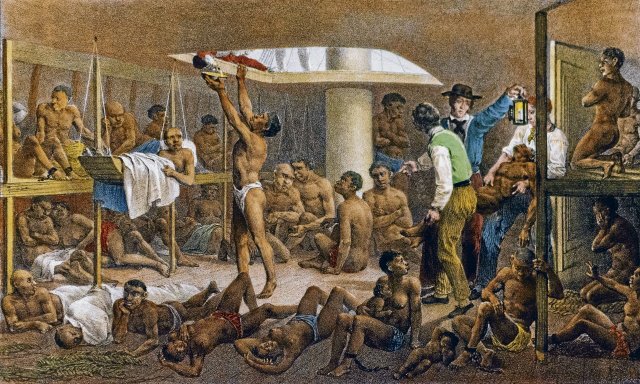

Up to 300 enslaved at 30 meters: Representation of the states under deck a “slave ship” around 1830

Foto: IMAGO/Heritage Images

Her book “The Slave Ship” was published in the United States in 2007, and the German translation only 17 years later. How do you explain this?

Of course, interest in the book always depends on how great awareness of the topics of race and slavery is in a country. “The slave ship” was now in 14 Languages translated. In Germany, the idea prevailed for a long time that the slave trade did not have much to do with its own history. What is not really true: The Brandenburg-Africa company, founded in 1682, was a very important player of the transatlantic slave trade.

Your working method is the historiography “from below”. What is the specific about it?

It is about reconstructing life and awareness of working people. The problem is, of course, that working people usually leave few documents. In the case of slavery, this mismatch is particularly extreme. Although one million people were shipped from the port of Ouidah in today’s Benin as slaves, we only have two descriptions of them in the first person. Overall, the transatlantic slave trade is quite well documented, but of course the slave dealers tried to extinguish the identity of people. A major challenge is therefore to read the documents left by elites against the grain. You have to develop a feel for what the powerful in their texts omit and disguise.

Interview

Wikipedia / thinktent Hwaaii

Marcus RedikerBorn in 1951, comes from a working -class family in the south of the United States, which shaped its access to social sciences. He studied at the University of Pennsylvania and was primarily devoted to the history of seafaring. Internationally, he became known with “Die Much-Hydra” (together with Peter Linebaugh, Association A, 2008/2000), in which the two authors reconstruct the history of the multi-ethnic lake proletariat on the Atlantic. With »Nd.Diewoche«, editor spoke about his book »The Slave Ship« (Association A, 2024/2007).

Perhaps you can describe a little more precisely what distinguishes the “historiography from below”.

It stands in the tradition of historians such as Lucien Febvre and Georges Lefèbvre in France or A. L. Morton in Great Britain. But with the social movements of the 1960s there was a real explosion in this field. Blacks, women, workers etc. not only called for political power, but also a new interpretation of history to re-look at race and slavery, US imperialism and, above all, the role of women. I have always understood my research work as a contribution to these movements.

In your book you describe the slave ship as a factory. The Afrokaribian theorist C. L. R. James wrote the same thing in “The Black Jakobiners” over the sugar cane. What do you mean?

The important thing about the observation of C. L. R. James is that it gives you another, less focused on the history of capitalism. In my first book “Between the Devil and The Deep Blue Sea”, which I wrote about the piracy in 1987 in the early 18th century, I first dealt with the thesis that we should interpret the sailing ship as a complex machine: Numerous workers from very different contexts are on board, are violently subjected to a strict discipline and have to cooperate in the service of the machine. In addition, the deep sea sailing ships for the development of capitalism were as important as the steam engine. Only the ship allowed Europe to force different world regions into a single world market.

But what does the slave ship produce?

Mass work and racial. People are expropriated in West Africa, drafted and then fed to the plantation system on the other side of the ocean. The surprising thing for me was that the ship also affects the production of “breed” categories. Usually the crew of a ship consists of 40 seafarers that come from different European countries, but also from Africa. So the crew is multi -ethnic, a colorful pile. When this ship approaches the West African coast, the seafarers become “white”. Not because of their skin color, but because they operate the machine. Conversely, the enslaves consist of very different ethnic groups. They are often put together in such a way that they do not speak a common language. If you arrive on the other side of the Atlantic, you are homogenized: the so -called Negro Race. Both groups are therefore racified, but interestingly, the seafarers lose some of the racial features at the crossing. So the ship produces racified identities.

How can you describe the social split on the ships? Does it make sense to speak of classes here?

One of my central questions was whether seafarers were solidarity with enslaved. In fact, this has rarely happened even with black naval men. This is because the boundaries between the skin colors have been “polished”. There was a dual terrorist system on board: one for the enslaves, another for the crew. There is a man’s report who was on a ship as a ten- or eleven-year-old as a enslave. Olaudah Equiano was absolutely shocked across the ship, he did not understand his function. The captain then put a sailor to death relatively early on the trip, and Equiano understood that it was not only a message to the team, but also to the enslaved. “If you treat yourself with each other, what will you do to us?” That was the dual terrorist system of these ships.

Nevertheless, there were also moments of solidarity.

Yes, the seafarers often suffered seriously – for example to Malaria. They were then simply left behind in the Caribbean or South America. I found indications that African women who knew how to treat malaria were kepting seafarers. So they took care of the same people who were responsible for the terrorist regime on the ships. I found this very touching, but it probably also had an instrumental aspect: if the seafarers were healthy, they were connected to these African women and could perhaps do something for them.

Nd.Diewoche – Our weekly newsletter

With our weekly newsletter . We’re Doing Look at the most important topics of the week and read them Highlights our Saturday edition on Friday. Get the free subscription here.

The black theoretician W.E. B. Du Bois speaks of the fact that the white working class draws a “psychological wage” through racism: it can feel something better. Can that also be said about the white seafarers?

I think that this wagon of whiteness also existed for seafarers, but that they played a smaller role. The crew was so multi -ethnic that it was difficult to develop an identity based on skin color. It was a colorful bunch of dipped, a motley mob. The work on board was racified from the 18th century and black seafarers were only allowed to do certain work. But in the 17th century, dealing was even more egalitarian, which was mainly manifested on the pirate ships.

How do you specifically imagine the situation on the slave ships?

On average, 300 enslaves and 40 men were on board. You have to see that these ships were not very large. For example, there are detailed drawings of the “Brooks” built in Liverpool. Although the ship was only 30 meters long and 8 meters wide, 500 people were often cried in. It was horrible, people were literally on each other. In South Carolina it was said that you could smell slave ships before you see them. Excrement, illness, death – that determined life on board. In the 400 years of transatlantic slave trade, the mortality rate was an average of twelve percent, but more than half of the people died in some crossings. Every morning the captain sent his people below deck to bring up the dead. They were simply thrown into the water. There were sharks that followed the slave ships on the way across the Atlantic.

An early industrial form of mass portation and killing. Why were there no more rebellions against it?

They occurred, but mostly occurred before a ship had moved far from the coast. On the high seas there was the problem of how to control the ship. In “The Amistad Rebellion” (2012) I wrote about a successful rebellion that occurred in 1839 before Cuba. It became possible because the enslaves were all trained militarily. In addition, one of the insurgents knew how to control a ship. When too many seafarers died during the crossing, the captain sometimes selected enslaved as sailors. It was probably the case in this case. The insurgents steered their ship north, were put to court in New York and acquitted so that they could return to Sierra Leone. But successful revolts of this kind were very rare.

The white seafarers were often not voluntary on board either.

Yes, white seafarers didn’t want to go to West Africa. The diseases and the situation on board were notorious. That is why the slave ships cooperated with pub owners and police officers. Those who ended in a pub or ended up in prison were often brought to the ship against their own will.

Her book “The Various Hydra” is a story of the transnational working class at sea. What could we learn from it for the political fights of the present?

Peter Linebaugh and I wrote the book against the prevailing historiography, in which the working class is made up of white men who earn their money in the factory. The working class is much older than that. The “pile of bunch” on the ships is so important because in this way the infrastructure of Atlantic capitalism was created. Today’s working class is the Motley Mob much more similar than classic industrial workers. Of course there were also division lines in the Atlantic proletariat, but at the same time there were also amazing forms of cooperation. The predominant concept of class blindly made us that there have always been fighting for black and white. The protests after the murder of George Floyd 2020 are for me in the tradition of these fights.

sbobet sbobet link sbobet sbobet