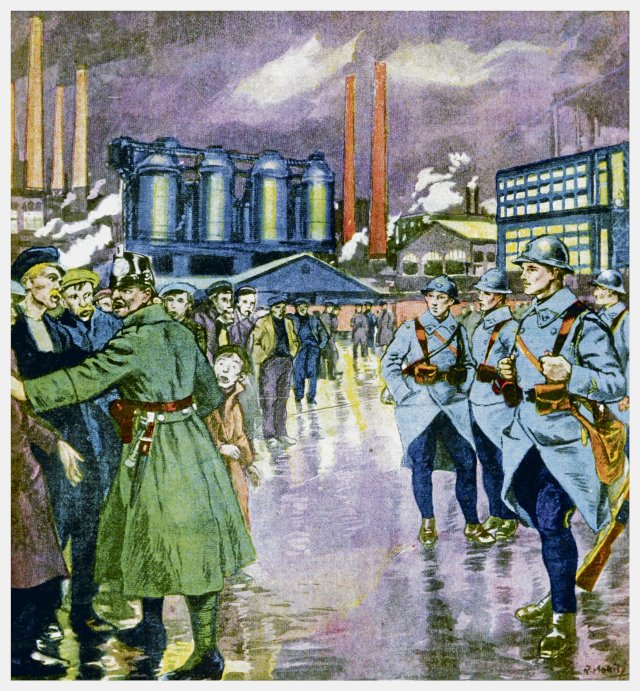

An account of the French occupation of the Ruhr in the conservative magazine Le Petit Journal (Paris, 1923)

Foto: imago/UIG

What remains of the many events, memorial hours, books, symposiums and exhibitions that commemorate 1923 in the year 2023, which is almost over? From a left-wing perspective, at least an ambivalent impression. That year was intellectually and philosophically productive: Karl Korsch, Georg Lukács and Ernst Bloch soon published books that became famous and introduced a non-dogmatic re-foundation of Marxism; The “Marxist Work Week” took place at Pentecost, the starting signal for the Frankfurt Institute for Social Research and the later Critical Theory.

Who betrayed us?

In stark contrast to this are the devastating political defeats of the left. The workers’ governments in Saxony and Thuringia were betrayed by the SPD and swept away by the Reichswehr. The “German October”, an attempt at revolution planned with great effort by the KPD and the Communist International (Comintern), was never even proclaimed, and the Hamburg uprising of the communists does not even qualify as a tragedy, it was so amateurishly planned and so comprehensive he failed.

When 1923 came to an end, the KPD was temporarily banned, hopelessly divided and had lost its reputation as a mass party. The party had lost two-thirds of its members, and instead fascism had now become a mass movement. The intellectual boom of Marxists and communists this year is countered by the loss of their revolutionary power. What’s more, there doesn’t seem to be any connection between the two; theory doesn’t illuminate practice. The books by Korsch, “Marxism and Philosophy,” and Lukács, “History and Class Consciousness,” seem too timeless to provide concrete instructions for action – even back then. And since no minutes of the “Marxist Working Week” have survived, we frankly know nothing today about whether it gave any impetus for a communist strategy.

In fact, there was a communist debate that sought to combine theory and practice with revolutionary intentions. It was published in the “Internationale”, the theory and debate magazine of the KPD, and it referred to the most dramatic situation for Germany, or more precisely, for the proletariat in Germany, in 1923: the occupation of the Ruhr.

Call for class compromise

As a reminder: The Ruhr area was occupied by French and Belgian troops on January 11, 1923 because Germany had not met reparation demands as a result of the First World War. The French and Belgians wanted to collect outstanding deliveries of wood and coal, and soon there were 100,000 soldiers between Duisburg and Dortmund.

On January 13th, the bourgeois government, supported by the Social Democrats, called for passive resistance against the occupiers: no cooperation at the official level, no release of raw materials and goods. Workers and entrepreneurs went on strike together, and the government in Berlin took over the “strike fund.” This prescribed fraternization of classes triggered a national frenzy that was immediately accompanied by racist and anti-Semitic fury. Jewish merchants were suspected of colluding with the occupiers, and the black and Maghreb soldiers in the French army were portrayed as sex-lusting monsters.

At the same time, the Ruhr area was the stronghold of communist and anarchist workers. The unions were therefore urged by capital and politics to control “their” base, which in concrete terms meant: no wage demands, no independent demonstrations by workers, no agitation against the so-called Ruhr barons (who, from the beginning and behind the scenes, were trying to balance the situation). the Lorraine steel industry, which was urgently dependent on coal from the Ruhr area), did not seek fraternization with the soldiers who themselves belonged to the proletariat in their homeland. The unions accepted this role willingly – but without being able to really control the workers. Class struggle unrest broke out again and again.

The communist cadres had to orient themselves in this confusing situation. The course that the party leadership proposed was, to put it politely, complicated and confusing. First, it granted the bourgeoisie on the Rhine and Ruhr an “objectively revolutionary role,” as it united the people against exploitative and oppressive occupiers. On the other hand, the same bourgeoisie was the driving force of German imperialism, which had lost a war in 1918 but not its ambitions. According to the KPD guidelines, the proletariat should wage a war on two fronts: against the French and against their own government.

“Summer” contradicts internally

This position provoked an almost prophetic contradiction in the “Internationale”, expressed clearly by a comrade who had given himself the pseudonym Sommer: the only goal of the German proletariat was the overthrow of its own bourgeoisie. Any political upgrading of domestic capital would only mean a strengthening of German imperialism, which would immediately prepare for the next world war if the opportunity presented itself – and a defeat of the French in the Battle of the Ruhr would be precisely this opportunity.

The unification of the people can only take place on the basis of nationalism, which in turn binds the proletariat to the fascist sentiments of the petty bourgeoisie and deprives it of its own class goals. Liebknecht’s slogan – the enemy is in your own country – still applies in 1923 as it did in 1914. Agitation among French soldiers, who should be addressed as class brothers, also becomes simply impossible if one shares the bourgeoisie’s request that the French and Belgians must disappear .

Despite his correct analysis, Sommer was dismissed within the KPD. This role was taken on by the party theorist August Thalheimer, who made fun of the fact that Sommer feared that Germany would soon be rearmed – not only inappropriate malice from today’s perspective.

He was also unable to refute any of Sommer’s arguments, but he arrogantly insisted on propagating the two-front war, which, for tactical reasons, granted the German bourgeoisie hegemony over the national resistance. When the French occupying forces executed the fascist saboteur Albert Leo Schlageter, the leading Comintern official Karl Radek dedicated an insightful speech to him and demonstrated: Nationalism had arrived at the heart of the communist movement.

The pseudonym Sommer can be deciphered after some searching. Behind it was the German-Czech Josef Winternitz (1896–1952), a doctor of philosophy, an acquaintance of Albert Einstein and a representative of “intransigent internationalism” – an unconditional internationalism whose repository was the German section of the Czech Communist Party (which was important for the Comintern at the time). KPTsch), passionately represented by its chairman Alois Neurath. This internationalism had its roots in the radical North Bohemian workers’ movement in Reichenberg, now Liberec. Its first theorist, even before the First World War, was Josef Strasser, who joined the ranks of the left-wing opposition from Rosa Luxemburg to Anton Pannekoek.

In his interventions, Sommer/Winternitz masterfully combined the abstract principles of this internationalism with the concrete fighting goals of the proletariat. Relating the correct theory to a practice that is in the process of development has been achieved here in an exemplary manner. Comintern leader Grigory Zinoviev described this internationalism as “absolute nihilism.” Anyone who yelps so loudly feels hit. However, the events of 1923 overtook this debate: in the fall, the governments in Berlin and Paris agreed on a mode of continued payment of reparations, and in the summer of 1925 the last French soldier left the Ruhr area.

What remains?

At the latest with the Schlageter speech, the KPD had lost its own theoretical compass; In 1925 it was completely replaced by Moscow’s directives, which from then on had to be followed slavishly. And Winternitz also followed, joined Ernst Thälmann and held high party positions for a while. He survived fascism in exile in England, was then unable to gain a permanent foothold in the young GDR as a western emigrant who was viewed with suspicion – and died in another exile in England. The German section in the KPTsch was purged of the left after 1923.

Winternitz’ texts on the events of 1923, those of his German-Czech comrade Alois Neurath and of course Josef Strasser’s “Urtext”, “The Worker and the Nation” (1912), remain worth reading. They show that workers gain nothing from entering into alliances that distract them from their class goals – and that difficult internationalism remains the only option even when an alliance with the national bourgeoisie and the petty bourgeoisie seems more promising “at the moment.” .

For further reading: The years of the »Internationale« are recorded digitally at:

www.max-stirner-archiv-leipzig.de/philosophie

Become a member of the nd.Genossenschaft!

Since January 1, 2022, the »nd« will be published as an independent left-wing newspaper owned by the staff and readers. Be there and support media diversity and visible left-wing positions as a cooperative member. Fill out the membership form now.

More information on www.dasnd.de/genossenschaft

slot demo sbobet88 link sbobet sbobet88