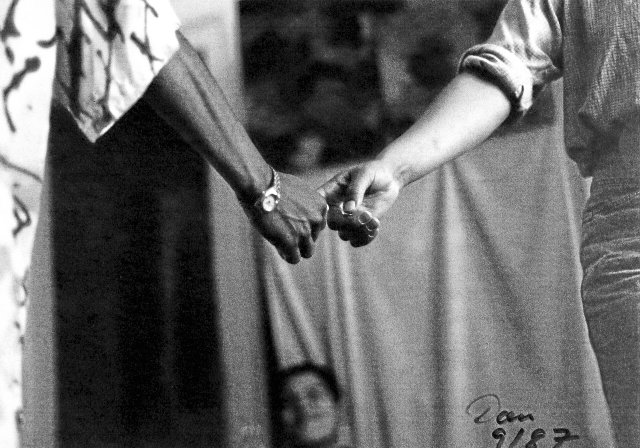

Detailed photo from the 1987 Federal Congress of the Black Women in Germany Network (ADEFRA)

Photo: Elija Tourkazi/Archive Gay Museum

The volume “Not the First” was recently published, in which stories from contemporary witnesses are archived and compiled. How did the book come about?

After moving to Berlin, I looked for a new political home. So in 2021 I met the writer Katharina Oguntoye at a stage discussion at Urania, moderated by the rapper Sookee. As a result, I met the singer Achan Malonda and our Berlin collective “QTI*BIPoC United” was born. This inspired me to research what migrant queers of color in Germany are connected to – politically and in terms of their everyday life.

Why did you just decide on this title?

A question that always bothers me: Why does it so often feel in social disputes as if there is no connection, as if you have to reinvent the wheel? You are always part of something bigger. The title refers to a quote from Jin Haritaworn in the book: “We thought we were the first, but that’s not true.”

In the book you talk about the “isolation” of marginalized stories. How does this affect queer and anti-racist movements?

You can be isolated because you grow up in a village in Germany and are a queer black or even white person. Or you come to Germany and don’t feel comfortable in the diasporic communities, for political or social reasons. Isolation has different dimensions, and a shared narrative breaks through them. In the book I try to create a collective moment through the diversity of biographies: Some people were born here, others fled here or migrated in another way. They share experiences despite their differences.

Interview

Omar Khlif

Tarek Shukrallah is a political and social scientist, community organizer and author. Shukrallah deals, among other things, with queer-of-color critical perspectives, queer movement history and intersectionality in Germany as well as sexual politics and political transformation in North Africa. The volume »Not the First. Movement Stories of Queers of Color in Germany” (Association A, 312 pp., br., 18 €).

Many of the stories in the anthology have a strong connection to Berlin. Doesn’t this create an imbalance between the center and the periphery?

It is important to talk about the blank spaces in the book. Forms of archiving vary in different diasporic communities, also because experiences with institutions vary. In addition, the archive structures are often limited to places like Berlin. Many of the materials used come from the Gay Museum, whose archive is gay, West German and white. It is also due to the transformation of Germany since the 90s that it is becoming increasingly difficult for queers of color to find spaces in other places. Many of the people who appear in the book have now moved to Berlin, even though they originally lived somewhere else.

Why did the focus fall on the 90s?

The fight for same-sex marriage and the successes of the gay and lesbian civil rights movement in the 1990s can only be understood in the context of the fall of the Berlin Wall. This moment didn’t mean the same thing to everyone. The rise of the Greens shows how equality policies were given priority over radical questions of respectability and anti-capitalist and intersectional struggles. For white middle-class gays and lesbians, the fall of the Berlin Wall was a window of opportunity to establish themselves politically, while more radical movements of the 1970s faded into the background. A new German identity politics promoted national pride and reconciliation, with Germany as a capitalist country at the center. At the same time, a racist pogrom atmosphere was brewing in the 1990s. This time, known as the “Baseball Bat Years,” was marked by racist violence and murders as well as experiences of isolation and fear for everyone who did not fit into the ideal image of German reconciliation. On this basis, successes such as marriage could be achieved for everyone, while racist and anti-queer exclusions continued to exist in parallel.

How did you decide who to talk to?

When I started researching, I realized that it made little sense to search for migrant and BiPoC voices along the canonized narratives of the gay or women’s and lesbian movements. Instead, I backward analyzed contemporary queer of color activisms to understand their stories. This is how I found my first conversation partners. After that, it worked on the snowball principle that I was always referred to other relevant voices in the conversation. I noticed that conflicts and contradictions often become clear in stories, which means that some stories penetrate and others don’t. I try to break this dynamic through the diversity of voices.

What makes art and culture so important for anti-racist and queer struggles?

Activism means more than just plenary sessions and demos. Political movements thrive on people making their voices heard and combining their interests. For this we need spaces in which people can speak. The anthology contains examples of spaces that were both cultural and political, even if they do not always describe themselves that way. I’m thinking of Zezé Soares, a black drag artist, or of spaces like the Salon Oriental, now part of Gayhane in SO36 in Berlin, and the Black Girls Coalition in Samariterkiez in Friedrichshain. These places made it possible to connect and process experiences of racism and queer hostility. They produced culture from their life experiences and created communities and advisory services.

nd.DieWoche – our weekly newsletter

With our weekly newsletter nd.DailyWords look at the most important topics of the week and read them Highlights our Saturday edition on Friday. Get your free subscription here.

Are there any stories that you consciously chose not to include?

I tell stories of people who have emancipated themselves and strengthened each other. I’m not telling the white gaze.

What was your highlight while working on the book?

My highlight was building sustainable relationships through this work. In times when right-wing extremist parties are gaining power, we need these relationships with one another in order to create common social spaces and pass on resistant knowledge.

What do you mean by “resistant knowledge”?

It is the knowledge of struggles and the memory of biographies and life experiences that defied social contradictions. It also includes the critical analysis of institutions and the development of political practices. Here there are also biographies that resist the comparison of queers vs. migrants.

For you, is the anthology primarily queer or anti-racist?

This comparison is problematic and results from social structures that play social issues off against each other. Some contributions in the book address why it often seems today as if queer and migrant-anti-racist concerns are in contradiction to one another. Here I continue the work of many before me, such as Koray Yılmaz-Günay, Jin Haritaworn, Fatima El-Tayeb and Peggy Piesche.

What patterns do you see in today’s discussions about migration and queerness?

Many of the documents in my book could be reprinted almost verbatim today. The Gay International of 1991 emerged as a resistance to the bourgeoisization of gay and lesbian organizations that drew racist boundaries. She addressed who has to choose between queerness and anti-racism. Then as now, we see similar exclusions, for example in the Common European Asylum System (GEAS) or the reform of the Self-Determination Act, which explicitly excludes people in the asylum process and under subsidiary protection and enables name tracking by the police. This hits migrant communities hard. Today’s Geas is reminiscent of the asylum compromise of 1993. Right-wing violence rages on the streets, and tightened asylum laws are passed in response. This repeats itself as a regulatory mechanism.

Why are migrant cultures of remembrance important?

The book “Show Your Color” by Katharina Oguntoye, May Ayim and Dagmar Schultz shows that black history began long before 1945. Migration has always been part of Germany, as have the struggles for recognition. My project follows exactly this point.

In the introduction you talk about the importance of battles that are waged “before us, with us and after us”. What do you mean by that?

Archiving is a political tool. I grew up in socialist and trade union circles, where songs and stories from struggles and political practices, some of which are centuries old, serve as reference points for the future. My project also creates an archive for a movement so that past struggles can be learned for future ones. It’s up to the next generation to carry this on. In addition, printed lines cannot be deleted so quickly.