Kant, with his forms of pure intuition, was still a long way from the curvature of space-time.

Photo: imago/Panthermedia

Space and time are omnipresent. Every thing has a place in space, every event happens at a moment or during a period of time. People’s lives and activities are also subject to this universality. Space and time seem everyday to us and yet mysterious: can they be traced back to something even more fundamental? Are space and time objective or subjective, that is, elements of reality or just human ideas? How do the entities space and time, matter and human beings relate to each other?

These are important philosophical questions. Great thinkers of the Enlightenment era searched for answers. Isaac Newton, Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz and Immanuel Kant presented three fundamentally different concepts. These are best understood through comparison. Kant was born in Königsberg on April 22nd, 300 years ago. The anniversary is the reason for this reflection.

Before matter or tied to it

Isaac Newton (1643–1727) opened his major work “Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica” (“The Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy”) from 1687 with definitions of basic concepts of physics, including space and time. It distinguishes the one “true space” and the one “true time” from the many situation-dependent “relative spaces” and “relative times.” The true entities are absolute, that is, dependent on nothing and unchangeable. Absolute space can be imagined as an ideal container that houses matter but remains unaffected. Absolute time can be imagined as the display of an ideal clock that sets the rhythm of matter without interference. The master describes it like this: “Absolute space, by virtue of its nature and without relation to any external object, always remains the same and immovable (…) Absolute, true and mathematical time flows in itself and by virtue of its nature and without relation to any external object. «

Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (1646–1716), Newton’s contemporary and professional competitor, saw it completely differently: space and time are relative, namely relations attached to matter. Space represents all positional relationships, time is the relation of succession. Without matter, the entities in question would not exist. In his scientific correspondence, Leibniz explains: “But space is nothing other than the order and relationship of the bodies themselves (…) Time is the measure of movement.”

Before and after the experience

The absolute versus relative dichotomy that goes back to Newton and Leibniz did not remain the same. Immanuel Kant (1724–1804) presents a third view in his 1781 work “Critique of Pure Reason.” First, he develops his own philosophical terminology: A priori means before experience, a posteriori means after experience. Intuition means thinking related to external objects. Pure intuition means intuition a priori. Conceptually equipped in this way, Kant claims: Space and time are forms of pure intuition and thereby “conditions of the possibility of experience”. To put it a little differently: Space and time are ideas that people are born with; This equipment is necessary in order to gain useful experience from raw sensations. In the “Critique of Pure Reason” Kant writes: “In order for certain sensations to be related to something outside me (…), the idea of space must already be at the basis (…) Time is therefore merely a subjective condition of our intuition. «

The philosophical schools of empiricism and rationalism argue about how knowledge comes about and whether sensory impressions or intellectual considerations are decisive. Kant now thinks that both – the objective and the subjective – must come together. He explains this explicitly using space and time. He is quoted in the epistemological context as follows: “Thoughts without content are empty, views without concepts are blind.”

There is not just one geometry

Because space and time are universal, many (basically all) sciences deal with them. Historically, mathematics has provided significant inspiration: in the 19th century, alternative geometries emerged as logically consistent theories, as an alternative to the geometry named after Euclid and which has always been taught in school.

Spherical geometry and the so-called hyperbolic geometry in three dimensions, collectively referred to as non-Euclidean geometries, attracted particular interest. There are two-dimensional models, i.e. surfaces, for the theories that emerged at the time. The spherical surface, also called a sphere, has a spherical geometry; certain hyperbolic surfaces of revolution have a hyperbolic geometry. Analog models exist in three dimensions, indeed in every dimension.

Mathematics has no problem with higher dimensions. In mathematical terms, Euclidean geometry, spherical geometry and hyperbolic geometry are equivalent. And in physical terms, that is, in terms of the real world? Carl Friedrich Gauß (1777–1855) and Nikolai Ivanovich Lobatschewski (1792–1856), the inventors of non-Euclidean geometries, asked themselves this. They devised large-scale practical measurements to decide between Euclidean and non-Euclidean. The “true” structure of space became a question a posteriori, not a priori. Epistemological apriorism lost its persuasive power.

Space and time as conventions

The mathematician Henri Poincaré (1854–1912) intervened in the debate with the curious view that Euclidean or non-Euclidean was only a question of theoretical and practical instruments; you get what you put into it. Poincaré is considered the main representative of so-called conventionalism, which – as the name suggests – considers fundamental parts of knowledge to be conventions, including statements about space and time. Such agreements are certainly necessary, but not specified in detail. With regard to the structure of space, the physicist Hermann von Helmholtz (1821–1894) refuted conventionalism: In a thought experiment, he showed that a traveler in hyperbolic space experiences completely different things than someone in Euclidean space.

Finally, the so-called empirio-criticism of Ernst Mach (1838–1916) should be mentioned, which first became known – and refuted – through Lenin’s controversial pamphlet “Materialism and Empirio-Criticism”. According to empirio-criticism, space and time, as well as other basic concepts, are nothing more than schemes for ordering sensations in the sense of an “economy of thought”. “Economical” here means arranged as simply as possible.

Restart with the theory of relativity

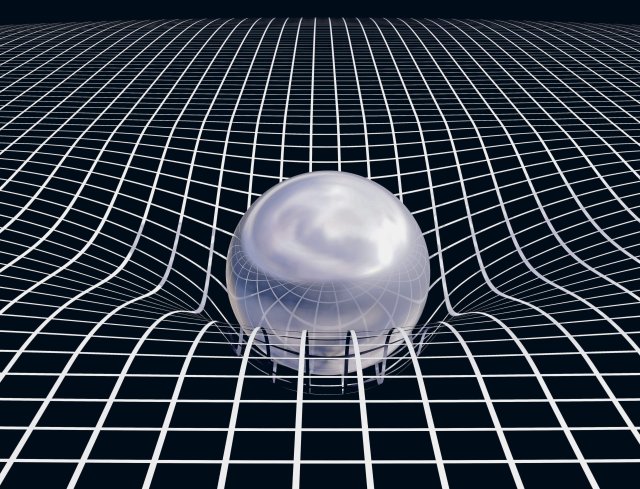

The natural philosophy of space and time was forced to “restart” by Albert Einstein’s (1879–1955) general theory of relativity (ART). The space and time of physics lost their respective uniqueness and independence; they merge into something larger – in the four-dimensional space-time manifold M. Subsequently, one can find three-dimensional relative spaces and one-dimensional relative times as suitable cuts through M. The respective physical situation determines the cuts. M carries a certain geometry, which is referred to by the technical term Riemann-Lorentz geometry. Einstein identifies this geometry with a physical field – the gravitational field. Physics thus becomes geometry, but not consistently: gravity (= geometry) is contrasted with the rest of matter. As revolutionary as ART came across, it was so successful. One empirical confirmation followed another, through measurements from the laboratory scale to the size scales of the cosmos.

Innate spatial ideas

An addendum is still due: in fact there is an apriorism regarding space and time; Kant is partially rehabilitated in this way. Behavioral research has found that monkeys and other higher animals are born with certain accurate ideas about space and time. Psychology has suspected or known this for a long time in relation to humans. The reason is clear: biological evolution. Having knowledge about the world you are born into is evolutionarily advantageous. To put it drastically – and negatively – the young monkey, which had inadequate spatial imagination, jumped too short to the next tree; he is not one of our ancestors. Evolutionary epistemology is the name of the field of research that deals with innate ideas in humans and animals in the course of evolution.

Subscribe to the “nd”

Being left is complicated.

We keep track!

With our digital promotional subscription you can read all issues of »nd« digitally (nd.App or nd.Epaper) for little money at home or on the go.

Subscribe now!

judi bola online link sbobet sbobet judi bola online