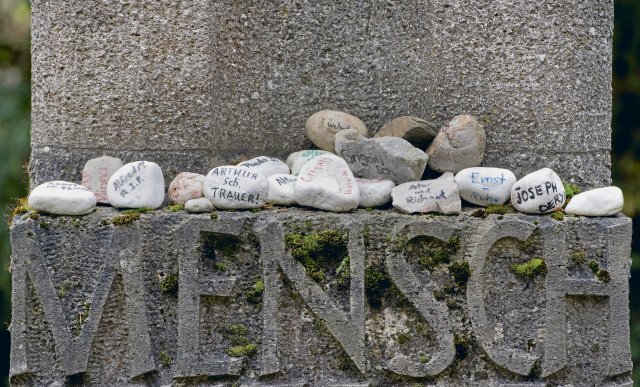

During the Nazi era, 15,000 people were murdered in the “Hadamar State Hospital” (Hesse). Colorfully inscribed stones in the memorial erected there commemorate her.

Photo: dpa/Boris Roessler

For decades there was silence about the German special approach to murdering people with disabilities. Only since the 1980s have works appeared with increasing frequency that at least begin to classify this horror and explore continuities and breaks. Dagmar Herzog’s book, the one, fits into this tradition Intellectual history of German eugenics traces, but at the same time is a genealogy of anti-ableism. Although it is also about perpetrators and eugenicists, Herzog thankfully places a strong focus on those who have strived for human coexistence throughout history.

She begins her presentation with Johann Jakob Guggenbühl (1816–1863), one of the pioneers of special education. Guggenbühl was convinced that children with so-called intellectual disabilities are capable of learning and placed the principles of “love and benevolence” at the center of his work. In order to finance his facility, he raised donations. Therefore, during his lectures he felt compelled to prove to donors that these children could also be “useful”.

nd.DieWoche – our weekly newsletter

With our weekly newsletter nd.DieWoche look at the most important topics of the week and read them Highlights our Saturday edition on Friday. Get your free subscription here.

Following this Guggenbühl period, a network of institutions and auxiliary schools was established in Germany that were intended to educate and shape people. The institutions in particular often had a Christian character and were part of the internal mission. Despite this religious superstructure, those cared for continued to be sorted according to their potential: the desire to separate care cases that required particularly intensive care into separate storage facilities cemented the boundary between “usable” and “unusable”. It was a fatal demarcation: in the 1940s, it was supposed to decide who was “just” sterilized and who was murdered.

In the 1890s, psychiatry moved into the realm of “idiocy,” which led to pseudo-scientificization. The primacy of the medical perspective over the pedagogical method led to the establishment of the concept of “racial hygiene”, which largely ignored the social prerequisites for disability – although it was already clear at the time that 85 percent of the so-called “imbecile” came from poor families. The focus on individual or intergenerational guilt while excluding the social perspective simplified the German special path that brought eugenics and euthanasia together during the Nazi era.

The decisive intervention that made this crime possible was a short text by the lawyer Karl Binding and the psychiatrist Alfred Hoche from 1920: “The release of the destruction of life unworthy of life”. In it, the two authors – highly respected in their fields and even beyond – spoke out quite openly in favor of the mass killing of all those whom they no longer considered human. They combined this proposal with an attack on the churches, which they accused of false pity; an accusation that Protestant actors in particular did not want to accept.

In the need to stay connected to the new era and its scientific nature, important thinkers and institution managers agreed on a position that, roughly summarized, said: sterilization yes, murder no. This flimsy compromise was intended to enable the churches after 1945 to claim that they were against the murder of disabled people and to delay coming to terms with their own responsibility for decades.

In her essay, Dagmar Herzog repeatedly points out the connections between hostility to people with disabilities on the one hand and classism and anti-Semitism on the other. Representatives of the church in particular saw the liberal sexual morality of the Weimar Republic and the decline in good manners – for which they blamed partly on the depravity of the lower classes, partly on Jewish intellectuals and journalists, and partly on the Social Democrats – as the main reason for this existence of disability. Some also resisted the idea of killing disabled people because they were used as a reminder of the consequences of a dissolute lifestyle.

The idea of destroying so-called unworthy life arose in 1939 and was quickly put into practice. This was not a project by a small leadership elite, but was supported by many perpetrators and accomplices. There was no legal basis justifying the murders of people with disabilities. No one, neither nurse nor doctor, who refused to commit murder was punished or even imprisoned. Murder centers like Hadamar stood in the middle of Germany, the ashes of the gassed victims rained down on the front gardens. When the gray buses carrying the victims to their deaths passed road workers, they took off their hats to show their grief; everyone knew about this destruction.

There were also people who spoke about it: the Münster Bishop von Galen, for example, preached against the murders that were known to everyone. That was one of the reasons they were hired. Another was that the method (gassing and spraying) was becoming too expensive. Afterwards, people were simply left to starve in the phase that scientists now call “decentralized euthanasia.” However, the knowledge gained from the gassings formed the basis for the extermination of Jewish people throughout Europe.

The line between good and evil is – to put it cautiously – vague, as shown by cases such as that of the Protestant pastor Ludwig Schlaich, who is still revered today as the father of curative education. Schlaich was open to sterilization, but opposed the killing of his students whenever he could. A book by him brings together the voices of those who were considered mentally disabled at the time. It couldn’t be published for decades because medicine feared for its good reputation.

The fact that there was no investigation into the euthanasia murders until the 1980s is still a scandal that is hardly noticed today. The continuity of hostility towards people with disabilities is only being broken very slowly; there is hardly any remembrance of the victims. For decades, doctors have written their doctoral theses based on samples taken in extermination centers. Important actors in this killing machine remained unmolested throughout their lives. Until the 1970s, sterilization of women who were considered mentally disabled was a standard procedure – today replaced by the trimonthly injection (a hormonal contraceptive administered by injection every three months).

Dagmar Herzog ends her essay with the 1990s, but many of the questions she raises still affect nursing and social work today. Guggenbühl’s concession to the audience to judge people based on their usefulness is one such dilemma – another is the dominance of doctors in the discourse of health and illness. Or the question of what a human is and what is not, and whether there can be gradations. And what to do with those who think that there should be gradations. Or why the churches got off so easily, especially the Protestant church.

These questions remain – but with her essay, Dagmar Herzog has given us the opportunity to understand and read the history of eugenics and ableism in a new way. That’s a lot.

Dagmar Herzog: Eugenic phantasms. A German story. Suhrkamp, 390 p., hardcover, €36.

Subscribe to the “nd”

Being left is complicated.

We keep track!

With our digital promotional subscription you can read all issues of »nd« digitally (nd.App or nd.Epaper) for little money at home or on the go.

Subscribe now!

judi bola online judi bola judi bola sbobet88