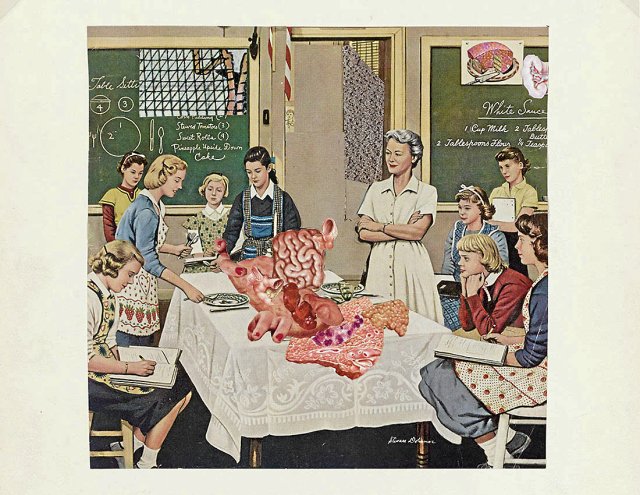

Do you want to eat that? George Grosz, “Cookery Class,” collage, 1958

Photo: George Grosz Estate

The Small Grosz Museum, already profiled in this newspaper, is located in the building of a former gas station in Berlin, near Nollendorfplatz. With the addition of an extension, the place looks like a kind of “gas station for losers,” as Gerhard Gundermann called it in a song: an oasis of encouragement for those who – then as now – feel trapped in a false reality.

George Grosz was one of those people. He wanted to remain an artist and not become a political agitator – which was not always easy for him given the prevailing spiritual abandonment. That’s why he invented collage, a playground that he simply called “sticky picture” back then. As a passionate player with images and image excerpts, Grosz was also a gifted legend maker. Legends are stories that thrive on suggestion, even if they happened otherwise; they are a question of vague precision. With Grosz we can read why the willful fragmentation of the material he found, mostly photographs, was such an artistic liberation for him. First, the common images of a beautiful, ideal world must be torn up or cut with scissors – i.e. destroyed – before the fragments can be put together into new images using glue and imagination.

nd.DieWoche – our weekly newsletter

With our weekly newsletter nd.DieWoche look at the most important topics of the week and read them Highlights our Saturday edition on Friday. Get your free subscription here.

This is the only way to get new views of the world. These are famous sentences from someone who, not least, knew how to stage himself, noted in 1918: “When John Heartfield and I invented photomontage in my Südder studio early in the morning at 5 a.m. in May 1916, neither of us had any idea of the great possibilities , nor the thorny but successful path that this discovery was to take. As is sometimes the case in life, we had struck gold without even knowing it.”

The world of images and meanings would subsequently be revolutionized through collage; the Dada movement made great progress in this regard. These invented images, composed of found particles, confronted the self-representation of politics and commerce with their more or less cleverly hidden ugly side. The images that then passed through the mind have completely lost their harmlessness.

The connection between George Grosz and John Heartfield harbored critical possibilities and even scandal. It proved particularly fruitful immediately after the end of the First World War. John Heartfield, along with his brother Wieland Herzfelde and his Malik publishing house, was undoubtedly more political in his ambitions than Grosz. For him, the collage was ultimately a means for his famous posters, with which he exposed Hitler and the NSDAP as criminals who were grasping for power in the 1920s.

Together, Grosz and Heartfield created collages that wanted to use simple visual means to educate people about political connections. In 1920, the collage “The Supports of the Altar, Throne and Fatherland” adorned a publication by the Malik publishing house. Then there is a drawing of three fat figures that are reminiscent of Honoré Daumier’s caricatures. But these drawings are – and this is new – partly covered with image fragments that have been “stolen” from the official self-portrayal of the representatives and are now being used against them. So we read under the collage with the three state-supporting figures (which look like alienated figurines): »We’re all pushing! We celebrate together! We only have one enemy: Russia!” Can you think of any current references to this?

The collages collected in the exhibition mostly come from the archives of the Academy of Arts in Berlin, with which the privately run Small Grosz Museum is showing this special exhibition on the first floor, while the permanent exhibition on Grosz’s artistic career can be seen on the ground floor is. The special collage exhibition was curated by Birgit Möckel and Rosa von derschulenburg. For her, Hamlet’s “rift in the world” is the central motif of George Grosz’s collage cosmos. Arming yourself against the destructive outside world with your own art world was his credo throughout his life.

In Berlin in the 1920s, he cast an evil eye on those who formed the staff of the Weimar Republic after the fall of the Empire: dark figures of yesterday, open or secret enemies of the republic. Greed for profit, militancy and class arrogance characterized this highly corrupt class, which ultimately found its leader in Hitler. With him they wanted to finally conquer Russia and exterminate communists and Jews.

Grosz also created stage sets with Heartfield, for example for Jaroslav Hašek’s “The Adventures of the Good Soldier Schwejk” for Erwin Piscator’s Proletarian Theater. These were also avant-garde in form, almost collage-like, as Grosz remembers: “In any case, Erwin inserted the photo montage appropriately into the stage frame, smoothly reassembled the old scenery and gave the stage the liveliness and fullness of action that the real theater has Must have.” As a “modern battle painter”, as the Grosz saw himself, he showed at every opportunity what war means for the soldiers: death and destruction, mutilation of body and soul, and ultimately the destruction of everything that has value.

However, the focus of this extremely intelligently designed small exhibition is on exhibits from George Grosz’s time in the USA, where he lived from 1932 to 1959. A few weeks after his return to Berlin, he died after falling down the stairs. Grosz’s passion for collecting, which is evident in his collage books, is interesting. A kind of picture diary, like the one he kept from 1941 to 1957 and which is entitled “Textures. The Musterbook« carries. Here he has compiled clippings from the New Yorker, department store catalogs and commercials in a highly apocalyptic manner. It resembles the bizarre world theater of Hieronymus Bosch, which he admired. The obscene overabundance of the world of goods celebrates a triumph here, which is accompanied by a constant urge to vomit. Mountains of meat and sausage, in between aggressively advertised whiskey and smiling fashion dolls whose eyes Grosz – if you look closely you can see – have gouged out, some of which has been painted over. Lots of monsters that are turning the advertised brave new consumer world into a modern hell.

What evil absurdity permeates these American nightmare scenarios, which seem to be created not from lack, but from abundance. The hype surrounding frozen food (a novelty that both repelled and attracted Grosz) and automated kitchen appliances is becoming apparent. Overall, a lot of weariness and boredom. This is also evident in the postcards that Grosz sent to friends. Changing a small detail is enough to distort a photo that at first glance seems friendly beyond recognition: the grimace takes the place of the permanently smiling face.

But he also viewed himself no less severely. So in 1947 he sent the art critic and collector Paul Westheim a postcard in which he mounted his head on a sailor’s uniform, with a pipe in his mouth and a white space where his right eye should be. But he lost it somewhere along the way. A deformed person, he too. What a sad joke that runs through these collages of the American era. You have the penetrating feeling of standstill and emptiness. It seems as if George Grosz is thinking back with melancholy to that time when the enemy still had clearly defined contours.

“George grosz. A Piece of my World in a World without Peace. The collages«. Until June 3rd, The Little Grosz Museum, Berlin.

#ndstays – Get active and order a promotional package

Regardless of whether it is pubs, cafés, festivals or other meeting places – we want to become more visible and reach everyone who values independent journalism with an attitude. We have put together a campaign package with stickers, flyers, posters and buttons that you can use to get active and support your newspaper.

To the promotional package