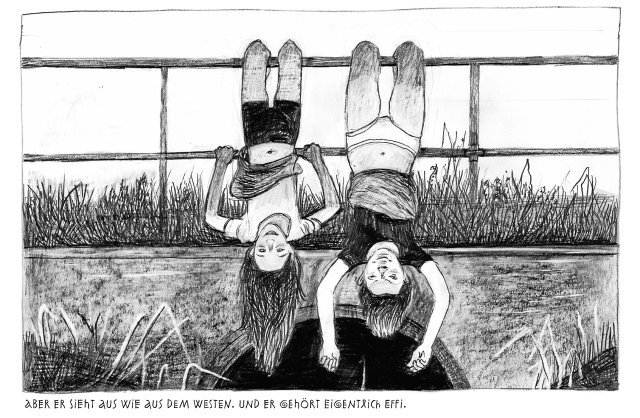

Situations and feelings can change very quickly.

Photo: Anke Feuchtenberger

A cuckoo egg is hatched by birds that are not the chick’s parents. Who is the father? The cuckoo knows! In this saying, the cuckoo replaces the word “devil,” and the devil is the personification of evil, for goodness sake. Dreams have come true in Cloud Cuckooland since the time of Aristophanes, and madmen are called “cuckoo” in English. The cuckoo and the donkey had a fight – both are despised by narrow-minded people. “Cuckoo” is a popular children’s game that draws its appeal from disappearing and suddenly appearing out of nowhere.

As incoherent as this introduction may seem, it is relatively close to the graphic novel “Comrade Cuckoo” by Anke Feuchtenberger. Rather than a graphic novel, this comic is a graphic poem or a graphic fairy tale that follows a visual-associative and emotional logic rather than a narrative one. Not that it doesn’t exist, but it only becomes apparent little by little, and not completely.

nd.DieWoche – our weekly newsletter

With our weekly newsletter nd.DieWoche look at the most important topics of the week and read them Highlights our Saturday edition on Friday. Get your free subscription here.

For the sake of orientation, it is partially reconstructed here, even if it feels a bit like lifting a stone, whereupon the many animals that live underneath evaporate: At the end of the Second World War, in the East German village of Pritschianow, women are murdered by Soviet soldiers Soldiers raped. The two fatherless girls Kerstin and Effi, who were presumably born a little later, grew up in the GDR – first in the crèche, then with their mother (Effi) and grandmother (Kerstin). Over time they become estranged from each other, and in the end Kerstin, who has moved away after missing her grandmother’s funeral, returns to the village.

However, this synopsis creates a completely false picture of the book. Because “Comrade Cuckoo” does not fit into the sniveling German victim discourse about the oppression in “two dictatorships” either in terms of content or form. Most of the time, the artistic engagement with the GDR takes place either in the style of anti-socialist realism or as a postmodern costume drama, in which the pop culture fascination for GDR design and products plays an important role (“Good Bye Lenin” or “Kleo”). But no matter whether it’s gray or brightly colored: all you see is the urban GDR, and usually there is a sometimes understanding, but more often accusatory comparison of the promises and reality of the workers’ and farmers’ state, whose farmers you never see.

“Comrade Cuckoo” is completely different: fields, forests and meadows are shown. You could call this bucolic, although this term should not be confused with “idyllic”. Closer to the cliché of fun country life, Feuchtenberger’s graphic novel is closer to archaic myths and surrealism. For large parts of “Comrade Cuckoo” takes the child’s perspective, and although children perceive their environment very precisely, they cannot fully understand it, which is why it often seems threatening. Situations and feelings can change very quickly, like in horror fairy tales, which have such an intense effect on no one as on children. This quality is particularly inherent in the images, which have a decisive influence on the book, as text is used rather sparingly: they are usually drawn in a style that may initially seem childishly naive, but at the same time they are so detailed and dark that the word “Naïve” seems inappropriate. These pictures know more than they show. An ambiguous naivety also characterizes Henri Rousseau’s paintings, but they are more friendly and harmless compared to Feuchtenberger’s lyrical-ironic black painting.

Feuchtenberger’s dark images are populated by characters from folk songs and the world of fairy tales: the child in the forest, the grandmother, the hunter with the rifle (even if he has the title “Waidgenosse”), the fox and the goose. And are people even people? They often have dog or pig heads, while human faces can be seen where they are not, such as on the back of a dog or the back of a spider. Like in the forest of horrors, these faces look at you, and not just them, but also genitals, or things that look like them. The vulva-shaped snails, for example, are omnipresent, even as protagonists. But the female form can also be seen in mushrooms that grow on trees or in the corners of rooms.

An eerie, subliminal sexuality pervades the book: “Everything is upside down. Pale roots stick out of the water. And in the hollow between the pale legs it is silky wrinkled and iridescent purple. Old scar tissue. Drops bead down. Jochen loses the ground under his feet while running away. The forest has tipped over and continues to swim towards him.” Over long stretches, “Comrade Cuckoo” shows the connections that the subconscious in the upper room makes between the undergrowth and the abdomen: “The undead beech tree lies with a spicy scent. The belly dusted with spore meal. “It also sprouts virginally from the oak tree.” The corresponding images are clearly ambiguous.

But snails and mushrooms are not only important as symbols from a graphic point of view: like sexuality at the time of the action (1960s), they live hidden and in the dark. The trauma of rape by Soviet soldiers is suppressed; it is explosive for political reasons. Analogous to the hermaphroditism of snails, in “Comrade Cuckoo” motherhood is decoupled from the existence of a father. Which brings us back to the cuckoo child.

In addition to the form and content, the appearance of “Comrade Cuckoo” is also remarkable. The powerful presentation is fitting for this visually powerful work with its images full of latent violence: golden lines shine promisingly on the black cover, the pages have a gold edge. No savings were made on the quality of the paper either, and the volume weighs 1.33 kilos on the kitchen scales. This puts it in the weight class of illustrated books, and as a coffee table book, “Comrade Cuckoo” can be picked up often even after reading it for the first time. Then you can enjoy the fantastic lettering with its lambda loops as “L”, its alpha-like “A” and its squiggle “G” or the beautiful drawing of a blackbird that looks at you curiously and sadly, or pointed ones Miniatures like this: »Rosi is reminded of something. She can’t believe it. It’s too close.” It’s incredibly sad, and incredibly beautiful.

Anke Feuchtenberger: Comrade Cuckoo. Reproduction, 448 pages, hardcover, €44. Also available as a limited special edition with screen print for €150.

#ndstays – Get active and order a promotional package

Regardless of whether it is pubs, cafés, festivals or other meeting places – we want to become more visible and reach everyone who values independent journalism with an attitude. We have put together a campaign package with stickers, flyers, posters and buttons that you can use to get active and support your newspaper.

To the promotional package