“Responsibility for form” was Arno Rink’s aesthetic credo.

Photo: Photo: Hirmer Verlag

1990 was not a good year for painting. Smooth photographs and flickering videos entered the art market with avant-garde vigor. An institution committed to traditional image genres like the Leipzig University of Graphics and Book Arts (HGB) was just as worried about its future as an Eastern company that was unprofitable according to neoliberal criteria. But barely a decade later, the glorious workplace of Bernhard Heisig and Werner Tübke was back in the spotlight, brighter and more international than ever before. Under the “New Leipzig School” label, painters such as Neo Rauch, Tim Eitel and others stormed from one sales record to the next.

Only one person initially remained surprisingly quiet: Arno Rink, the midwife of this renaissance. As the only rector of a GDR art academy who was confirmed in office after reunification, he led an unsettled faculty and a young generation looking for support through the critical bridging period. Who, if not the thoroughbred painter with the square skull, would have had what it takes?

From an early age, he was given the image of a powerhouse, persistent and hard-drinking, famous and infamous for his professorial rigor. If he didn’t completely tear apart a piece of work when marking it, that was almost the only form of praise students could expect from him.

nd.DieWoche – our weekly newsletter

With our weekly newsletter nd.DieWoche look at the most important topics of the week and read them Highlights our Saturday edition on Friday. Get your free subscription here.

But Rink’s personality as an artist and teacher had many facets, as his now published diary notes reveal. For years and decades he struggled with the monsters of an unstable psyche: doubts about his own artistic work, fear for his family and himself, money worries despite his professor’s salary and finally a long-term illness with cancer.

After the painter previously only put a few thoughts on paper, he started keeping a regular diary in 1998. Severe depression forces him into a psychiatric hospital. Torn away from the lively academy business, he ends up in the world of closed doors and high doses of psychotropic drugs: the “mobility of everyone involved,” he observes, “is reduced to a kind of slow motion.” Sensitive people should almost be advised not to read it, Rink describes the abysses they experience so meticulously. In the vicious circle of crying fits, anger and lethargy, art takes on a new significance as an antidote. “Time is deadline” is scrawled on the wall of the studio. The diarist sees this as an imperative to create what is possible within increasingly narrow limits. The last entries were made shortly before his death in 2017. He was able to fend off illnesses and crises for almost two productive decades after the diary entries began.

The mood logs put the inner gloom into hearty words: “Today I got really angry with my head, my brain, that this little piece of gray, convoluted shit is dictating my whole life.”

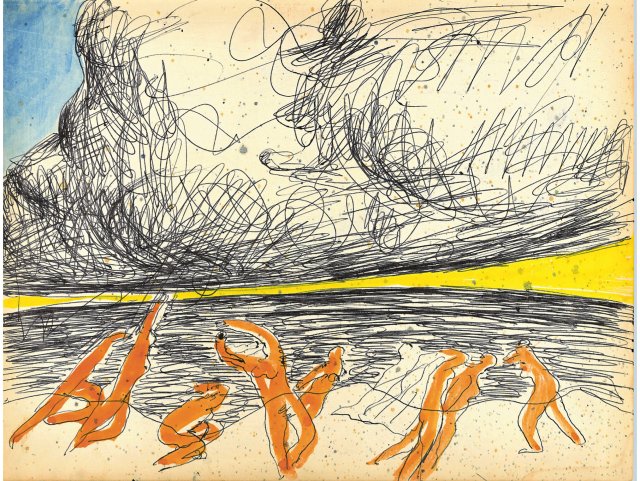

Even more than in previous pictures, the aging man becomes a human painter, constantly seeking a dialogue with Giotto, Courbet or Picasso on paper or canvas. The label of the untimely, whose pathetically depicted nudes seem to have been taken far from history, is probably why Rink only recently received more museum attention again in unified Germany. “I am not a modern artist,” is the title of the volume edited by his widow Christine Rink, which is supplemented by accompanying texts from some of his companions.

In fact, Rink had already struggled with socialist realism, which had become a doctrine, in the GDR. Because his work takes up classic visual themes such as “Lot’s Daughters” or “Judith,” old design problems are given a new interpretation. “Responsibility for form” is the aesthetic credo. The late work in particular concentrates on lonely walking figures, empty backgrounds and surprisingly combined colors. References to the present disappear, although the native Thuringian was never apolitical. For example, he registered the burgeoning right-wing extremism of the 90s early and clairvoyantly in terms of its causes and consequences.

Nevertheless, it is Rink’s artistic attitude that initiates a conservative turn in painting. His Eleve Michael Triegel, creator of – one could almost say – portrait of the ruler of Benedict XVI, continues this line most clearly. The master himself, on the other hand, is no longer able to build on the exhibition successes from GDR times.

Rink’s creative pride suffers openly from the disregard and reacts offended when a press report about him only has black and white illustrations. To compensate for the feeling of lack of recognition, he takes refuge in hobbies that are rare among cultural figures: shooting and driving a Porsche.

Rink’s pedagogy is derived from the realization that the artistic profession is one of the most difficult of all and that capitalism makes the sperm race for orders even tighter: »I try on a narrow path to make young people stable for life. That gives me a lot of joy and I’m not a dad, but can be pretty hard.” The diaries, however, only comment sparingly on the work of the young star graduates, at least in the version edited by the widow. The only thing that becomes clear is the close collegial and friendly bond with Neo Rauch.

None of this was originally intended for publication, so you have to forgive a few repetitions and banalities. Nevertheless, there is a lot to be taken away from the volume, which is particularly illustrated with sketches and photos. On the one hand, because readers follow first-hand the genesis of an early work that wrestled with its own existence and with the big questions of painting. On the other hand, because you get an unusual backroom look into one of the most renowned art academies in Germany. Arno Rink may complain about the small details of the appointment committees, the departmental meetings and the expert work – hardly anyone has identified as he has with the HGB, where he has worked for more than half a human life. He usually called it “the school.” His school.

Arno Rink: I am not a modern artist. Diaries, sketchbooks, notes, letters 1960-2017. Hirmer-Verlag, 400 pages, hardcover, €34.90.

Subscribe to the “nd”

Being left is complicated.

We keep track!

With our digital promotional subscription you can read all issues of »nd« digitally (nd.App or nd.Epaper) for little money at home or on the go.

Subscribe now!