It at least has to look serious: filmmaker Julia Beerhold waves to her father in the golden Mercedes (photo from the family album).

Photo: Mindjazz Pictures

This text is about the explicit description of violence against children. For anyone who has had similar experiences, reading could have a retraumatizing effect.

Every family has a secret. But for most people it’s probably something harmless. The father secretly wore women’s clothing, the mother had an affair, and the grandmother hid money for decades. But there are also secrets that shape an entire life, that destroy souls, that cause damage that is impossible or very difficult to repair. Julia Beerhold’s very personal documentary “Behind Good Doors” is about this kind of secret.

Everything starts innocently enough. We see children’s film footage on Super 8. Little Julia is fooling around with her brother at the coffee table, stands in front of the school with a large bag of sugar when she starts school, is lifted on her shoulders by her father, and is kissed on the cheek by her mother. But the music that Beerhold puts under these scenes suggests that there is a break with the supposed idyll. The drums are hard, the guitar just as merciless. The lyrics are more shouted than sung »Julia, your name is like summer. Go go go, set this world on fire” (Julia, your name sounds like summer. Go, go, go, set the world on fire) promise unrest in paradise.

And that’s how it is. In one of the next scenes, Julia Beerhold confronts her mother and retells a scene from her childhood: As a little girl, she sits at the table on Easter Day and a relative is visiting. Julia receives several hard slaps in the face because she was disobedient. And because that’s not enough humiliation, the father also takes photos of his crying daughter, and the mother and uncle laugh at her. The father later even sticks the photos in the family album. Even at this point, when the film has only been running for 20 minutes, you actually want to leave the cinema, it’s so difficult to endure the humiliation and shame that was part of everyday life in this family. But you don’t want to begrudge the parents this victory and then watch Julia Beerhold deal with the trauma of her life for 79 minutes.

The Beerholds are apparently a well-off normal family. The father is an engineer, the mother is a pharmacist. After 14 years of marriage, the two had their first child, Julia’s brother Jens. You move into a self-designed bungalow with a large garden. The second child, Julia, was born six years later. Both are dream children, with the flaw that they came so late. The parents work a lot. At home you can let go, party and drink, with your camera always with you. Julia and her brother receive lots of presents at Christmas and birthdays, and there’s even a pony. Modern indulgence trade.

nd.DieWoche – our weekly newsletter

With our weekly newsletter nd.DieWoche look at the most important topics of the week and read them Highlights our Saturday edition on Friday. Get your free subscription here.

Beerhold draws a very detailed picture of her family using a mix of shaky handheld camerawork, her own family shots and long shots of the house and conversations with her mother. You often see her in front of the camera herself, a conscious decision to get out of the victim role.

The father, a jovial guy who is difficult to grasp. He, who died 20 years ago, is usually seen with a cigar. Even when sledding with the children, the economic miracle had to burn. He is violent, but unlike his mother, he usually beats his children emotionally and locks them in the basement if they don’t behave. But he can also be very loving, as Beerhold describes. Brought the children everywhere and picked them up again. When Julia turns 12, he quits his job and from then on is just a househusband. A patriarch in an apron. Her mother, in turn, scares her; she is actually permanently absent, and when she is present, she hits harder than her father – and with announcement. The children should go to the bathroom and wait there to be beaten with the whip.

In “Behind Good Doors” Julia Beerhold raises many questions: What is private? What public? Is education a family matter? Should we let bygones be bygones? Who is guilty?

Beerhold is brave, she has the conversations with her parents that we never dared to have: “Why did you do that?” “How can you hit someone you love?” The answers from the mother, who was at least prepared to talk to her daughter about it and be filmed, are typical defensive reactions: That’s just how the times were back then. It was normal to spank your children if they disobeyed. Feelings were radically suppressed, locked away in a place that was never allowed to be reached. At one point the mother also talks about how the Nazi era made her this person, and you can tell in her tone that that can only be half the truth and somehow works well as an excuse. One would like to believe that: evil breeds evil. But Julia Beerhold was born in 1965, 20 years after the end of the war. And she then asks the crucial question: But it must have felt wrong?

“Behind Good Doors” is an important film because it is not a private matter, but shows how power and powerlessness work in what is actually the best protected space there is: the family. Even today, around 50,000 cases of family violence against children are recorded every year; the number of unreported cases is certainly significantly higher. The film proves that violence knows no classes and that the power of repression can become incredibly strong when a person is unable to articulate needs and feelings. Because Julia’s brother Jens deals with his childhood experiences completely differently. It was never as bad as she describes it in her film, and he no longer wants to remember some of the blatant attacks. After filming ended, he broke off contact with her. Not without repeating it again: Julia, his sister, is the person who has caused him the most damage in his life.

In one scene, Julia Beerhold asks her mother why she treated her children like that, since she really wanted to have them, and the mother answers cold-heartedly: “When you were there, that was fine.” And something else is happening here new panorama that could talk about motherhood and regret, but is never the subject of the film. It is also subtly about the social pressure that presents home and child as a blueprint for a successful life and perhaps it is also about postnatal depression, something that had no terminology at the time when Helga Beerhold became a mother, but as serious illness must still have existed. But the film also tells about the kind of people such an upbringing produces: people who make love dependent on conditions, who extort affection with fear, who associate feelings exclusively with violence and recognition can only come from outside.

But Julia Beerhold is rightly not interested in the big picture, because her film is a reappraisal of her own history. Julia Beerhold became addicted to alcohol and drugs at a young age; her relationships, whether friendships or partnerships, were always characterized by violence, power games and humiliation. She runs away from home as early as possible and lives in a car for a year. The main thing is to get out. She has made three suicide attempts.

And yet Julia Beerhold sits at the coffee table with her mother in the nursing home, twice a week. The other residents are already jealous. And this on a woman who inflicted so much violence on her daughter. Why does Julia Beerhold do this, why does she show the affection she never experienced? She doesn’t find an answer to this in the film. But she probably sums up the most important thing in this sentence at the end: “In order to let go, I had to look.”

“Behind Good Doors”: Germany 2024. Director and screenplay: Julia Beerhold. 79 minutes. Start: May 30th.

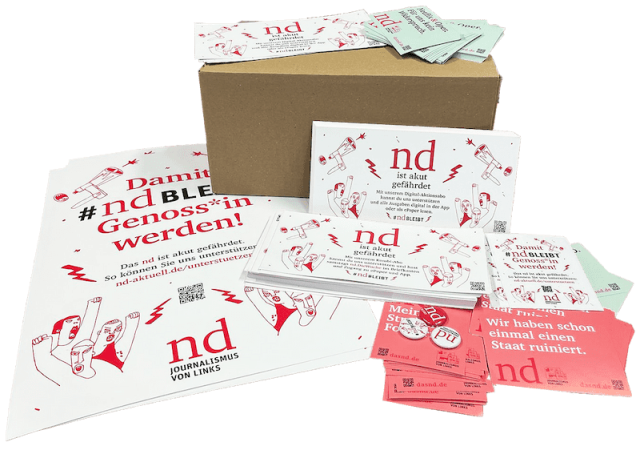

#ndstays – Get active and order a promotional package

Regardless of whether it is pubs, cafés, festivals or other meeting places – we want to become more visible and reach everyone who values independent journalism with an attitude. We have put together a campaign package with stickers, flyers, posters and buttons that you can use to get active and support your newspaper.

To the promotional package

judi bola online judi bola online judi bola judi bola