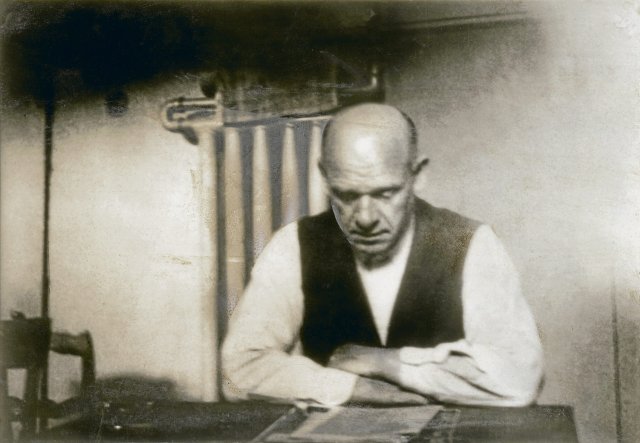

Ernst Thälmann in his prison cell; one of the last photos of the KPD chairman

Photo: Archive

On August 14, 1944, a few weeks after the failed assassination attempt on Hitler, Heinrich Himmler, the “Reichsführer SS” and Reich Minister of the Interior, went to the “Wolf’s Lair” for an unusual conversation with his “leader”: only Hitler personally could decide the fate of such prominent opponents and critics of the regime as that of the former German ambassador to the Soviet Union, Werner Graf von derschulenburg, or the marshals Günther von Kluge and Erwin Rommel. The list that Himmler carried with him also included the name Ernst Thälmann, who had been the head of the KPD from 1925 until his arrest in March 1933.

Initially, the Hitler government had planned to try Thälmann in a major trial and, with the verdict against him, also to impose a verdict against the entire communist movement. After months of work, an indictment was put together that would prove Thälmann’s continued “high treason.” The trial before the infamous People’s Court was intended to “bring revelations of extraordinary importance about the communist danger that threatened Germany and the world,” as a high-ranking official in the Reich Ministry of the Interior put it in February 1935.

But there was no great enthusiasm for the process among the Nazi authorities. The memory of the embarrassing defeat at the Reichstag fire trial in the fall of 1933, which had ended with the triumph of Georgi Dimitroff, the “Lion of Leipzig,” and the acquittal of the four communist defendants, was too fresh. And the public prosecutor had great doubts that the evidence against Thälmann would be sufficient for the desired death sentence or at least life imprisonment.

After the start of the trial had been postponed several times, the decision was made in November 1935 to forego a trial against Thälmann. A senior Gestapo employee had previously announced that there were “other and less harmful ways to keep Thälmann in safe custody.”

For Thälmann, the cancellation of the trial was a great disappointment. He was convinced that, like Dimitroff before him, he would have succeeded in winning an acquittal. At the beginning of 1944 he celebrated himself in a secretly written autobiographical text: “Even my worst enemies would have been surprised that a former transport worker from Hamburg, who had not attended a secondary school or a university, but who had unexpected popular and other life experiences and practical ones If he had knowledge of life, he could succeed in denouncing and exposing the entire legal and judicial comedy.

Now Thälmann was hoping for an exchange with the help of the Soviet government, as he repeatedly told his comrades. He was worried “that the party would rather have him inside rather than outside, otherwise the propaganda would be over,” as Rosa Thälmann reported to a courier from the KPD’s foreign leadership at the beginning of 1938. In the days and weeks after the signing of the German-Soviet non-aggression treaty (the so-called Hitler-Stalin Pact) in the late summer of 1939, Thälmann was certain: “Hopefully the hour of my liberation will soon come. I am firmly convinced that the Thälmann case was brought up during the negotiations in Moscow (…).

But Stalin showed no interest in Thälmann’s fate. He neither wanted to be reminded that the policies of the KPD, which had been prescribed to the party by Moscow before 1933, had failed in every respect, nor did he want to allow another top communist functionary alongside Dimitroff to draw light that was exclusively for it was intended for him, i.e. Stalin. Above all, however, Stalin was not prepared to put the functioning of the unnatural treaty with Hitler’s Germany to an unnecessary test because of a “trivial” such as Thälmann’s fate.

At the beginning of the German war against the Soviet Union, Thälmann had to realize that there was no longer any realistic chance of being released. It speaks for his human greatness that even in this hopeless situation he was not prepared to make the declaration that his tormentors repeatedly demanded, with which he would have admitted his failure as a communist and thus bought his way to freedom.

Thälmann knew that he would not live to see the end of the war. In January 1944 he noted: “There is even a probability, as cruel and as hard as it is to say it here, that if the Soviet armies advance dangerously for Germany and in connection with the associated deterioration of Germany’s overall war situation, the National Socialist regime will do everything to checkmate the personality of Thälmann. The Hitler regime will (…) not shy away from getting Thälmann out of the way early or finishing him off forever.”

Thälmann’s premonition came true with cruel consequences. At the conversation between Hitler and Himmler on August 14, 1944, the final decision was made: “Execute.” This meant that the death sentence was imposed on Ernst Thälmann without a trial, literally with the stroke of a pen.

An alarm sounds

There were several songs from the communist movement that Ernst Thälmann sang about. The best-known poem is probably that written by Kurt Bartel (Cuba), which expressed the hope of quickly overcoming the division in Germany and whose refrain is probably familiar to every citizen who grew up in the GDR: “Thälmann and Thälmann above all!/ Germany’s immortal son. / Thälmann never fell,/ Voice and fist of the nation,/ Thälmann never fell,/ Voice and fist of the nation.” The earliest, in turn, written by Erich Weinert in 1934, was still animated by the hope that Thälmann would be released from Nazi imprisonment to be able to liberate: “The alarm sounds: The murder court/ wants to cut off his head./ But when the world sets off into a storm,/ then they won’t dare./ Tear away the ax that is already rushing down!/ For comrade Thälmann: Raise your fist!”

With his name on their lips, German communists went into the Spanish War to defend the Popular Front Republic against the Franco fascists. The Thälmann Battalion (later the Brigade) had its own song, intoned by Paul Dessau, known worldwide in the interpretation of Ernst Busch: »Stir the drum! Drop the bayonets!/ Forward, march! Victory is our reward!/ Break the chain with the freedom flag!/ Let’s fight, the Thälmann Battalion./ The homeland is far, but we are ready./ We fight and win for you: Freedom!”

The first thoughts about murdering Thälmann had already taken place before July 20, 1944. In the spring of 1944, the Reich Security Main Office first talked about secretly killing Thälmann. In view of the impending military defeat, it was part of the Hitler regime’s strategy to “get rid of” all opponents who could have played a key role in a post-war Germany without Hitler and fascism. This is how the plan arose to take Thälmann to the Buchenwald concentration camp at a certain point and to murder him there. On August 17, 1944, the time came to put this plan into action.

Despite administrative assistance from the GDR, the Federal Republic’s judiciary was not prepared to hold the perpetrators responsible.

In the late afternoon, Thälmann was taken in a car from Bautzen, his last place of detention, to Buchenwald, accompanied by several Gestapo officers. The arrival of this special prisoner had already been announced there. The prisoners who would otherwise have to work in the crematorium were locked in their accommodation as a precaution. SS men had taken over their work that evening. Shortly after midnight, the car with Thälmann arrived at the crematorium through a separate gate. While Thälmann was being escorted through a “trellis” of SS men, three shots were fired, followed a few minutes later by a fourth. As ordered by Hitler, Ernst Thälmann was murdered.

Regardless of the many millions of deaths that were caused by German fascism, Hitler and his satraps were not prepared to accept responsibility for Thälmann’s death before the world public. The Reich Propaganda Ministry therefore had the news spread in mid-September 1944 that Thälmann had died in an Allied air raid on the Buchenwald concentration camp on August 28, 1944.

However, the course of the crime against Thälmann and those involved were already known immediately after the end of the war through the statements of the former Polish prisoner Marian Zgoda, who secretly observed the events on the night of August 17th to 18th, 1944. But for literally decades, the judiciary of the old Federal Republic, despite extensive administrative assistance from the GDR, was neither willing nor able to adequately hold the perpetrators accountable. The murder of Ernst Thälmann remained unpunished.

From our author, Dr. Ronald Friedmann, member of the speaker’s council of the Left Party’s Historical Commission, will soon be publishing a new, detailed Thälmann biography

Subscribe to the “nd”

Being left is complicated.

We keep track!

With our digital promotional subscription you can read all issues of »nd« digitally (nd.App or nd.Epaper) for little money at home or on the go.

Subscribe now!

judi bola online sbobet88 sbobet link sbobet