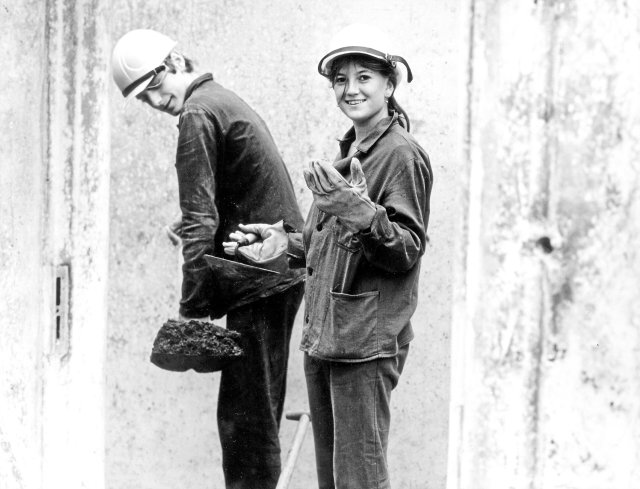

Such pictures only existed in the GDR.

Foto: picture-alliance/ ZB/Manfred Uhlenhut

Mr. Graeff, how did you come to feminism?

Alexander Graeff: My upbringing was strongly influenced by patriarchy. We all suffered under my grandfather, especially the women in the family, but my father, my brother and I also experienced his dominance as very restrictive. I come from a lower-middle-class, village background with the classic division of labor: the men bring home the money, the women take care of the children and the household. After fleeing the provinces at the age of 21 – first to Karlsruhe, then five years later to Berlin – I was socialized more by women and continue to be so to this day. I have always lived with emancipated women who also saw themselves as feminists. When I was 26, I was able to study in Berlin and also deal with feminist literature and theory.

How was it for you, Ms. Klemm?

Gertraud Klemm: I grew up in middle-class circumstances, very sheltered, I would say. Nevertheless, I always noticed that something was wrong. I then read Feminists quite early on. It really hit me when we were involuntarily childless and adopted two children. It was a shock how this motherly role was imposed on me. From then on I also started writing seriously.

Interview

Natalia Reich

Natalia Reich

The term feminism is interpreted very differently by different actors: so differently that different schools now seem to be irreconcilable. But are there perhaps similarities and what might they look like? The Austrian writer and biologist Gertraud Klemmborn in 1971, describes in her books – always bluntly and often with a lot of black humor – the failure of the promises of emancipation and the ongoing social burden of being a mother and/or a woman. Most recently, her novel “Einzeller” was published by Kremayr and Scheriau. Alexander Graeffborn in 1976, is a writer, philosopher and literary educator. He heads the literature program at Brotfabrik Berlin and advocates for greater visibility of queer people and topics in the literary world. Most recently, his story “This Better Half” was published by Herzstückverlag.

Her first novel, “Aberland,” was about how two women fail because of the demands of emancipation. There were some discussions by feminists who said: This belittles women, this is anti-feminist.

Clamp: Yes, there were some wads there. It was mainly women who accused me of misogyny, often feminists from an older generation who had individually realized their utopias in the big city and didn’t want to hear that women’s liberation wasn’t as far along as they would like would have. Admittedly, the novel was very successful at the same time.

In my opinion, the debates surrounding feminist issues have become significantly more intense, including in the conflict between second wave and third wave feminism. Is that too schematic?

Clamp: I perceive it that way too. The last five to ten years have left me very disillusioned. Now I think there is no feminism at all, just many fragments of feminism. This is also because there is this compulsion to confess certain beliefs and one is constantly threatened with being excluded if one does not recite the creed obediently.

Graeff: I also see that ideas of a “pure doctrine” are circulating again, at least in parts of the movement. This is further reinforced by the concept of identity and its dualistic tradition. By distancing oneself from the other, one’s own self is made strong, which then cements collective identities that no longer see the self vaguely and as a bricolage. As a result, an emancipating self is destroyed again. By the way, I am absolutely in favor of the self, even in literature. For the individual stories and experiences and for making sure there is enough space for them. However, I would disagree when it comes to exclusions based on religious beliefs. It’s often the other way around: the fears of cancel culture and speech bans are conservative inventions to suppress progressive lifestyles.

Clamp: I would be happy to have public discussions with third wave or queer feminists, but these discussions are avoided or actively prevented. I can talk about the differences privately, but there are hardly any forums for this in public. Of course, this is also due to the way capitalist journalism works. In the “discourse” it is better to emphasize what pops, it clicks better and clicks are worth money. This capitalist logic is not about content or even understanding.

Where do you see the line of conflict between the second and third waves, from the feminism of the 60s to the 80s and what came after?

Clamp: I think second-wave feminism was two-dimensional: there was this clear antagonism between women’s roles and men’s roles, and people were rebelling against that. Of course there were shades of gray, but the basic conflict was manageable. With third wave feminism and all the intersections, it suddenly becomes three-dimensional, and a lot of new categories have been added in a very short period of time. That can also be overwhelming. It is also difficult for some older generation feminists who have fought against forced prostitution for decades to accept that sex work can simply be work. But there are both: forced prostitution and self-determined sex work. Complex problems just don’t fit into a colorful Insta mantra. This applies to all feminist controversial topics.

Graeff: In my opinion, this question is part of the conflict because it also brings a dualism to the fore. For example, if Simone de Beauvoir had been asked about the rights of workers or the issue of racism, she would certainly have identified this as a problem. Reality and society have become more complex, also because we have found language for previously marginalized parts of society. This can certainly be overwhelming, but old, reductive language often helps to crudely reduce the complexity of reality. So yes, the terms have become more precise, but a supposed break between two camps is artificial.

A break that has become worse since parts of the queer feminist movement see Hamas as part of a liberation struggle.

Clamp: The queer feminist solidarity with Hamas is completely incomprehensible to me. Anyone who thinks about it for even five seconds and who cares about people must recognize the hatred of women and queers in this terrorist group.

Graeff: It is true that there is a small part of the queer feminist bubble that parallels their own fight for freedom with the terror with which Hamas mistreats people. This radicalization arises precisely through the aforementioned fantasies of a “pure doctrine” and a dualistic friend-enemy scheme.

Where do you see points of contact between the camps?

Clamp: We basically want the same thing: we want to live and love with dignity, not to be hurt or degraded. And I don’t begrudge the patriarchy this victory over feminism. But I also see a problem that there is a distribution struggle. There is so much talk about diversity, for which there should be positions and money. There is also a need for a budget for women’s medicine, for ethnomedicine, for new medical territory. The area of diversity is getting bigger, but the feeding trough isn’t growing with it. Of course, a culture of envy arises. Diversity is not something that is created through individual representatives or figureheads, but much more diversity is needed in parliaments, in the parties, and also where the money is distributed. That should be a common political demand.

Graeff: I see it that way too. For example, with the subsidies invested in cars, the entire cultural and educational sector could be fully financed. The fact that there is no redistribution is a problem.

What would you like to see for future internal feminist debates?

Graeff: In any case, it is understood that this I that has been strengthened and needs to continue to be strengthened is a relational I. In my opinion, the idea of an autonomous self, detached from the world and other subjects, is just as harmful as the idea of collective identities. So I would like to see more solidarity among each other in feminist discourses.

Clamp: I hope that feminist theory will be tested for its practical suitability and that feminism will once again set priorities that are suitable for the majority. That common goals are pursued instead of arguing about everything and anything. Feminism cannot and does not have to please everyone! Feminists should put on their rubber boots and trudge back to the age-old construction sites: abortion, protection against violence, gender pay gap. Everything is still unfinished, enough work for everyone!