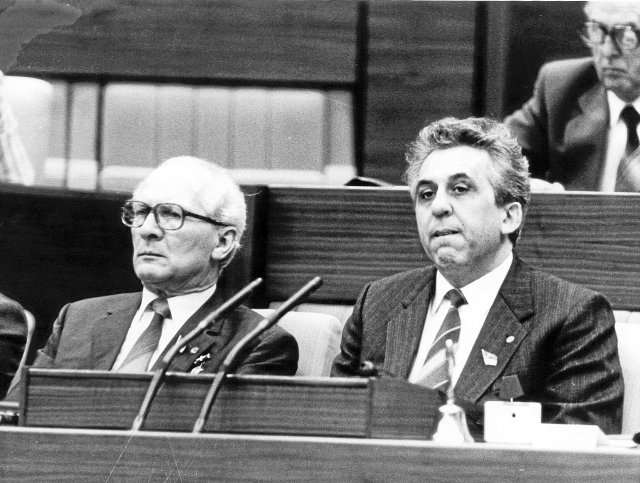

Tension between two men: The old and the new General Secretary of the SED, Erich Honnecker and his successor Egon Krenz, Berlin, October 25, 1989

Photo: photothek

He writes at the beginning of the book that he doesn’t have a doorbell. When he doesn’t have visitors, his door is open to guests. When reading this book, it is as if Egon Krenz were sitting across from you as he talked about his life. He speaks of his experiences, expresses his opinion, polemicizes against the defamation of GDR biographies and will thus speak from the hearts of many.

He supports the GDR as an “alternative to a Germany that was responsible for two world wars and the cruel fascist dictatorship,” emphasizes that 4,142 Nazis and war criminals were expropriated and “520,000 former Nazis were removed from public office.” Higher education now also for workers’ and farmers’ children, equal rights between the sexes, deletion of paragraph 175 from the penal code… And no NVA soldier set foot on foreign territory to take part in combat missions.

This book will be well received, but will also be met with rejection and silence. When Konrad Adenauer took the train to West Berlin, he is said to have drawn the curtains so as not to see the “Asian steppe.” “For him, Siberia began behind the Elbe.” But this is a statement for the East – and a personal review – in amazing detail. In color, not black and white. Egon Krenz confronts you with sincerity and honesty. He wants to be fair, not to defame anyone, and yet the question remains as to why the GDR collapsed and whether something could have been done differently.

Elected first secretary of the Central Council of the FDJ in 1974, candidate in 1976 and member of the Politburo in 1983 – as the youngest among the old men, he became a confidante of Erich Honecker. He has seen its struggles and problems up close. What was not communicated to the public: The social policy goals ambitiously formulated at the 8th Party Congress became increasingly difficult to finance because labor productivity did not increase to the same extent.

»You want oil, grain, raw materials from us. And what do you do with it? Give it away. Raise wages, improve pensions, introduce shorter working hours, give young people interest-free loans and expand vacation leave instead of investing in industry. And what’s even worse: You sell our supplies to the West in exchange for foreign currency. What Soviet Prime Minister Alexei Kosygin complained to him in 1976 remained a fundamental problem. “If we had as few goods in our stores as they do in Moscow, we could give up the GDR straight away,” replied Honecker, to whom he reported this conversation.

In the period between 1974 and 1988, which this second volume of memoirs by Egon Krenz covers, a whole tangle of difficulties arose. Kosygin was right: the GDR was hungry for foreign currency. But that was not the only reason why the party and state leadership wanted to improve relations with the Federal Republic of Germany. For Saarland native Erich Honecker, détente in the spirit of peace was a matter close to his heart. He ambitiously sought diplomatic success and was annoyed when he was thwarted in Moscow.

The border between two areas of power ran between the GDR and the Federal Republic of Germany. Special intra-German relations were not desired in Moscow. Every attempt to open up the country – be it by making travel easier or by switching telephone lines to the west – was criticized. Stones were repeatedly put in Honecker’s way when he wanted to meet with German politicians. That was the case under Brezhnev, Andropov, Chernenko and also under Gorbachev, who later took credit for German unity. Egon Krenz believes that he wanted to grant the socialist countries more independence is a legend.

Even “free from all-German feelings,” Egon Krenz had respect for the clever tactician Honecker, who was increasingly annoyed at not being “master of his own house.” »Honecker wasn’t interested in separating from Moscow. He just wanted to be seen as an equal.” There was no doubt about the necessity of the Warsaw Pact, but economically there were differences when it came to the financing of the Soviet armed forces in the GDR, the prices for raw materials and their delivery. “Can the Soviet Union help us economically or do we have to rely on cooperation with the West?”

Brezhnev accused Honecker of national arrogance. At that time, the USSR was almost at the bottom of the socialist countries in terms of living standards. In 1981, Brezhnev announced that Soviet oil supplies would have to be cut by two million tons in order to increase exports to capitalist countries. The cause lay in a new round of arms race with the USA and three bad harvests in a row. The consequence was that a new energy structure in favor of raw lignite had to be created in the GDR – with corresponding consequences for the environment.

How the “leading comrades” were constantly in a predicament, exacerbated by self-made problems and personal tussles – much that was previously unknown is revealed in this book. “Erich, was that necessary?” Kurt Hager asked after Biermann’s expatriation on November 16, 1976, which Honecker had decided on entirely alone. “You know how critical the Soviet comrades are of our current policy towards Bonn,” he received in response. “Should we take on the SU about Biermann?”

There was constant maneuvering between the major powers, and in Bonn as well. The deplorable information policy in the GDR was also linked to the Western media. They didn’t want to provide ideological ammunition and often left citizens in the dark when it came to controversial issues. Mistakes were not admitted. As a literary editor at the “Zentralorgan” it sometimes seemed to me like an attempt at word magic: as if success were achieved through incantation.

Honecker’s ambitions lay primarily in foreign policy, as the book says. A critical look falls on Günter Mittag, who as head of the Economic Commission had extensive powers and commanded ministers and combine directors. The billion-dollar loan, arranged in the summer of 1983 by Franz Josef Strauß and Alexander Schalck-Golodkowski, the head of the commercial coordination department in the GDR Ministry for Foreign Trade, initially gave the GDR a breathing space. Economically. Politically, however, it was an ice age. Wojciech Jaruzelski imposed martial law against the protests and strikes in Poland from 1981 to 1983, not least due to Soviet pressure. Egon Krenz believes that he saved the world from a military conflict. On November 22, 1983, the Bundestag voted in favor of stationing new US medium-range missiles in the Federal Republic. A day later, the USSR broke off disarmament negotiations. Nothing would be left of Germany if a war broke out. In contrast, Honecker wanted to develop his own GDR peace strategy, a “coalition of reason” with the Federal Republic of Germany. “He had in mind a GDR that could have been a mediator between the West and the Soviet Union.”

On November 25, 1983, Egon Krenz was nominated as Secretary of the Central Committee, responsible for security, youth, sports, state and legal issues. In 1984 he was appointed deputy chairman of the State Council. Because he did not condemn Gorbachev’s policies across the board, Honecker began to distrust him. He probably knew about Moscow’s considerations regarding a new beginning in Berlin. His plan was clear, on the XII. to be re-elected at the SED party conference in 1990.

“All too often we judged what came from Moscow with a self-flattery for which there was absolutely no justification,” the book says. But While Gorbachev was looking for a way out of the economic and political crisis, he would have needed the help of all allies. “Nobody can say today how the world and the GDR would have developed if the socialist states had developed a common concept for a real socialist renewal.”

Egon Krenz: Design and change. Memories Volume 2, Edition Ost, 446 pages, hardcover, €26.

nd-Literatursalon with Egon Krenz on January 31st, 6 p.m., Franz-Mehring-Platz 1, 10243 Berlin

Become a member of the nd.Genossenschaft!

Since January 1, 2022, the »nd« will be published as an independent left-wing newspaper owned by the staff and readers. Be there and support media diversity and visible left-wing positions as a cooperative member. Fill out the membership form now.

More information on www.dasnd.de/genossenschaft