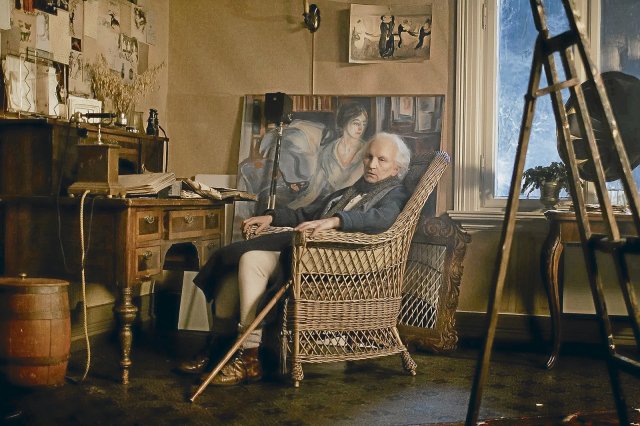

In the master’s studio: The old Edvard Munch is played by Anne Krigsvoll.

Photo: Splendid FilmStars

“A feeling is also a way of thinking,” muses Edvard Munch in Henrik Martin Dahlsbakken’s kaleidoscopic art house drama, which takes him, the most famous Norwegian painter, as its subject. Munch’s picture “The Scream”, one of the most important paintings of the 20th century, is probably known to most people. Even Homer Simpson plays table football with “The Scream” in a daydream sequence. However, one should find out about the key biographical details of this pioneer of expressionism before watching Dahlsbakken’s formally extremely ambitious film, which obviously wants to convey to the audience the artist’s torn personality.

An actress and three actors embody Munch in different phases of his life in wildly mixed storylines. This is reminiscent of Todd Haynes’ unconventional film biography about Bob Dylan, in which six actors bring different facets of the musician to life.

The 21-year-old Munch is sensitively played by Alfred Ekker Strande. In 1885, the young man, who was prone to melancholy, spent his holidays in the countryside with his family. According to his father’s wishes, he should rest there and paint. The deaths of his mother and his older sister are, incomprehensibly, hardly discussed in the film, which aims to convey a feeling for the painter’s mental state. Munch captured this traumatic experience, which was formative for him, in numerous paintings.

During his shore vacation, Munch falls madly in love with the writer Milly Thaulow, but she does not reciprocate his feelings to the same extent and breaks his heart. Dahlsbakken suggests that because of this first great disappointment he preferred to remain unmarried throughout his life.

In another, short storyline you meet Munch, who is eight years older and played by Mattis Herman Nyquist. At first you are confused when this hipster-like version of Munch suddenly pulls out his cell phone, because Dahlsbakken has simply transported the 29-year-old into our present. At this age, Munch was invited to a solo exhibition by the Berlin Artists Association. But as soon as it opened, the exhibition developed into a scandal: the pictures, which did not correspond to the spirit of the times, were dismissed as unfinished and the exhibition was closed again after just seven days. The deeply frustrated Munch then goes around with his friends and gets drunk with them in a techno club.

In a haunting scene, Munch then cycles across the former airport site in Tempelhof on the luggage carrier of his friend, the Swedish writer August Strindberg – who, like Munch’s oldest version, is portrayed by a woman. In the background, an expressive, painted sky shines like in his paintings, which seem more relevant than ever in their emotional intensity and their expression of existential fear. So it’s not surprising that Dahlsbakken, almost half a century after Peter Watkin’s film biography of Munch, has decided to revive his spirit.

About a year after the closure of his exhibition, which went down in art history as “The Munch Case,” the 30-year-old painted his most famous picture: the scream of a deeply disturbed person in a world that has spiraled out of control.

The third storyline is shot in black and white and in 4:3 format. In this episode you are nightmarishly close to the 45-year-old artist, both because of the setting and the soundtrack. He is now an alcoholic who is terrified that he will develop inherited schizophrenia. Munch, now played by Ola G. Furuseth, suffers a breakdown and ends up in a mental hospital in Copenhagen. There he is cared for by a psychiatrist who is reminiscent of Freud, with whom he has rather clichéd and tiring conversations about (male) genius and madness.

The 80-year-old Munch, who can be seen right at the beginning of the non-linearly told film in his house in Oslo, tries to keep his works safe from the Nazis in occupied Norway in 1943. Anne Krigsvoll most impressively embodies the idiosyncratic artist, who is already in poor health and lives a very withdrawn life surrounded by his numerous paintings.

Even if Dahlsbakken’s formally unconventional film has its gaps and occasionally drifts into the cliché of a male artistic genius, it at least arouses curiosity about the work of this melancholy painter who broke so radically with the traditions of painting that his pictures survived for two centuries later appear incredibly contemporary. How great that there are currently two worthwhile exhibitions of his paintings in Berlin and Potsdam – and a building specially constructed for his works opened in Oslo two years ago.

»Munch«, Norway, Director: Henrik Martin Dahlsbakken, 105 Min. Start: 14.12.

Subscribe to the “nd”

Being left is complicated.

We keep track!

With our digital promotional subscription you can read all issues of »nd« digitally (nd.App or nd.Epaper) for little money at home or on the go.

Subscribe now!