Change something together, radically and organized? Nope. Infinite happiness can only be found within oneself.

Photo: imago/Frank Sorge

There was a time when the word “toxic” was still original. It was creative, it was lyrical, it was Britney. It’s now everywhere – on the Internet, in everyday life and of course on book titles. Especially on life guides that talk about how, in the tradition of Marie Kondo, you can remove unnecessary things from your life. Instead of things, it’s now about people. You have to check your counterpart again and again in order to expose them as bad and dangerous. The word has long since found its way into feminism – especially in the form of “toxic masculinity”. What is meant is the form of masculinity in which men harm themselves and others – as if there were a good form of masculinity. Nowadays everything can be toxic anyway. Friendships, family members, bosses, rules, reactions and habits. All of this has the potential to prevent us from loving ourselves, functioning, and moving forward. That’s why you have to remove toxic things from your life – no therapy, no accommodation, no stopping, only cleaning will help.

The two current book titles that get the esoteric word out of the advice bubble are benefiting from its triumph. “Toxic” sets out to replace terms such as power, violence and abuse – just as the word “problematic” previously replaced the words right-wing, racist or fascist – in order to finally expand it as an attribution to everything that one finds stupid can. Everything can’t be so great anymore. Sophia Fritz has written a non-fiction book with biographical elements (“Toxic Femininity”), and Frédéric Schwilden has written a pop novel (“Toxic Man”). If both had chosen other titles, they would have done more justice to the content of their books, but both obviously chose the commercially safer bank – fair enough.

For Schwilden, the term seems to function as a kind of common thread: every man in the novel is damaged in some way by patriarchy, every woman has suffered from it in some way. He probably also wants to provoke a bit – after all, he always lets his protagonist fire off stupid prejudices about young leftists, which suggest that the author doesn’t know anyone personally, but just hangs out on strange Instagram pages every now and then.

Schwilden’s protagonist thinks that people are generally doing too well these days. Poverty in the novel only exists in the form of homeless people and beggars that you come across every now and then. He uses these poor marginal characters to give his Bürgi novel, which is about the loss of his father and becoming a father between exhibitions and parties, a dose of street. He doesn’t want to be accused of being completely blind, of course. Otherwise he is completely blind to and unaffected by real conditions.

Fritz, on the other hand, wants to appropriate the expression “toxic femininity” that she has read among anti-feminists in a feminist way, without, however, defining what toxic actually means – and perhaps coming to the conclusion that the term is not suitable for explaining conditions, but can only provide vague attributions.

Fritz takes the path of most current feminism books, she tries – based on her own socialization – to explain larger connections and mostly sticks to individualizations, even if she sometimes points to structures, the system or capitalism – but more like that it would be about the sky under which we have to live. It is inconceivable that there could be anything beyond capitalism; the appeal is to work on yourself and your environment. In this book, too, we find ourselves in bourgeois circumstances in which one has of course suffered from sexist socialization, from pop culture images that have negatively influenced one’s self-image, but one is little affected by exploitative circumstances – one can counteract one’s own condition with conversations, courses, Massages, therapy and coaching.

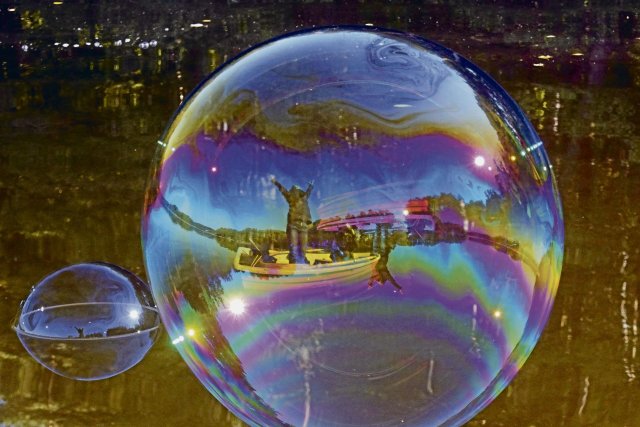

In both books you learn something about gender, love, sexuality and the complexity of being affected and being a perpetrator, and both books are linguistically successful and bring together clever ideas. But they are in no way radical. The authors live in bubbles in which people say that everyone can be the creator of their own happiness. Women and men – that’s just what happened to both of them, it’s little more than “the pictures” that we saw and that were shown to us.

Of course, both of them think about the topic of class in some way, but it doesn’t play a role. Of course, a novel doesn’t have the task of going on such a search for clues, but unfortunately it doesn’t take place in non-fiction books either. Behind Fritz’s demands, which are correct – honesty, not being so hard on yourself, setting boundaries, holding other women and yourself responsible – there is no greater goal, no utopia. This is also due to this unsuitable word “toxic”, which suggests that it can only ever be about behavior and never about circumstances. Fritz may have appropriated the term, but that’s not a win.

If you don’t want to talk about capitalist power and violence, you won’t be able to explain why these distortions in terms of gender and class exist and why we can’t just get out of it like that. In the toxic bubble, class is a sideshow. Problems that arise from this are individualized and the addressees are ultimately encouraged to be selfish, so that our only goal is to get ahead as individuals – of course also through consumption.

The novelist at least knows that he is on this trail. As a feminist, however, you should think about the system in which women can really be free from their own and other women’s oppression. To do this you no longer have to concern yourself with yourself, but more with everyone else, together, organized, political and radical.

Sophia Fritz: “Toxic Femininity”, Hanser, born, 192 pages, 22 €.

Frédéric Schwilden: »Toxic Man«, Piper, born, 288 pp., €22.

Subscribe to the “nd”

Being left is complicated.

We keep track!

With our digital promotional subscription you can read all issues of »nd« digitally (nd.App or nd.Epaper) for little money at home or on the go.

Subscribe now!