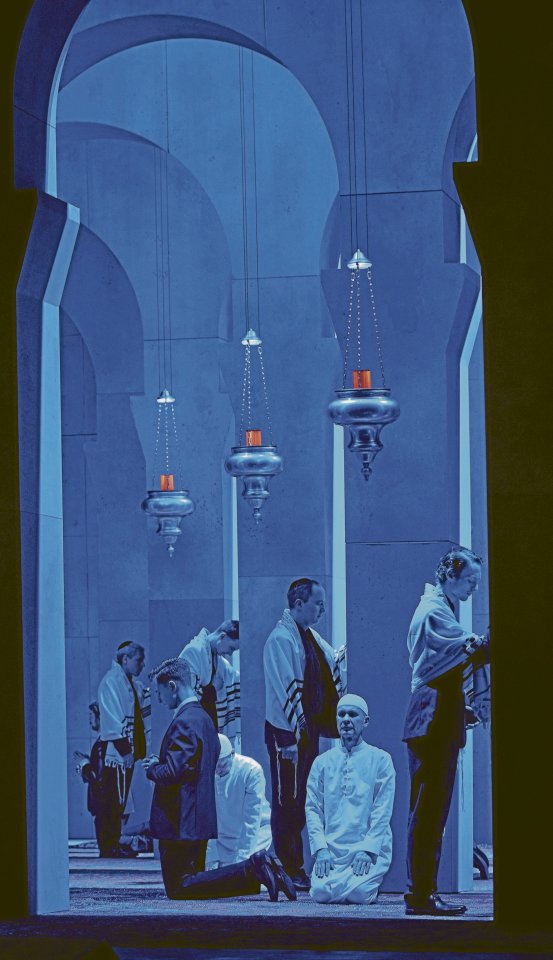

It should be possible: an understanding between Christians, Jews and Muslims.

Photo: Ludwig Olah

The beautiful Jewish woman Rahel and the Castilian King Alfonso, a couple in the midst of the religious wars on the Iberian Peninsula in the 12th century – this subject interested many artists. A highlight of this series is the novel “The Jewess of Toledo” by Lion Feuchtwanger, in which the medieval religious fanatics stand for the reactionaries of the 20th century.

The same title is given to a tragedy written by the Austrian playwright Franz Grillparzer after the failure of the 1848 revolution. The main character is of course the king. From an early age, Alfonso has never known anything other than work for the state and is easy prey for the seductive Rahel in his loveless marriage. But he soon returns to his duty in the state. He finally accepts that his loyal followers are too quick to kill the Jewish woman. The monarch has become a whole person through the experience of love. In the end, it is the official duty that counts; in this morality, the death of the woman is ticked off as a necessary sacrifice.

Hans-Ulrich Treichel wrote a libretto for Detlev Glanert based on the drama by Grillparzer. Actually very free: the plot structure remains intact, but the evaluations are reversed. To achieve this, Treichel brings the political to the fore. The Castilian grandees, including the spiteful queen, want a war against the Muslims. Alfonso doesn’t want that. Rahel represents a different world. Grillparzer is interested in how a king loses himself and how he disciplines himself again. He leaves out the sensual things in between. It occurs in Treichel and especially in Glanert’s composition. These are utopian passages of de-hardening, and director Robert Carsen stages an understanding between representatives of Christianity, Islam and Judaism in the background.

It just can’t last. The queen and nobility denounce Rahel as a spy in the service of the Muslims. Alfonso has to choose between giving up power and betraying his beloved. Unlike Grillparzer, he agrees to the murder of the Jewish woman. In the end he is a representative of the state again. While Rahel’s sister mourns the death in the foreground, the choir loudly prepares for war. With projections of weapons and then bombed-out buildings, as can be seen in Ukraine and Gaza, Carsen relates the final act to the present. The fact that the “FAZ” suspected anti-Israel activities here does not necessarily speak against the production. Carsen does not impose an idea on the work, but rather develops his ideas from the work.

From a musical dramaturgical perspective, this all works exceptionally well. There are no lengths in the almost two hours of pure playing time. Glanert’s composition is based on traditional patterns in terms of expressive characters and form. It is an aesthetic that relies on communication with the audience. It’s about something today that needs to be conveyed, but not trivially and not without effort.

At times the music is so dense that the audibility suffers. However, this criticism weighs little compared to what has been achieved in this opera: the concise characterization of the main characters and the abundance of orchestral colors that carry the action and connect to familiar sound models without ever falling into cliché. The cheers from the premiere audience were huge and justified. Glanert’s musical aesthetic stands for what makes sense today: preserving opera as an art with an audience, not making this audience too comfortable, and setting tasks that can be solved by a sympathetic ear.

Jonathan Darlington’s conducting contributed to the success, as did the casting of the main roles. Among them, Christoph Pohl deserves particular mention as Alfonso, to whom the composition also allows the greatest variety of postures. He is sometimes showy as a ruler and tender as a lover. Alfonso proves to be helpless and weak compared to Queen Eleanor, who relies entirely on the logic of power politics and thinks of little more than hatred and death. Tanja Ariane Baumgartner gives this character the violence and sarcasm that the score demands.

As I said, Treichel escalates the political conflict compared to Grillparzer. There is extensive moralizing in the drama. In the opera, however, it is clear that Eleonore and Manrique are planning a coup against Alfonso and that they can only save themselves by turning against Rahel. Grillparzer glorifies state morality, Treichel and Glanert criticize a state that destroys love and wages war. They enhance the private sphere. We are certainly more comfortable with this today. The question is whether – as long as there is a threat of war in the world and one state is a potential enemy of the other – both sides of the conflict between happiness and duty should not be emphasized in the work of art. That would be the step from the sad to the tragic.

Next performances: February 26th, March 1st, March 8th

#ndstays – Get active and order a promotional package

Regardless of whether it is pubs, cafés, festivals or other meeting places – we want to become more visible and reach everyone who values independent journalism with an attitude. We have put together a campaign package with stickers, flyers, posters and buttons that you can use to get active and support your newspaper.

To the promotional package