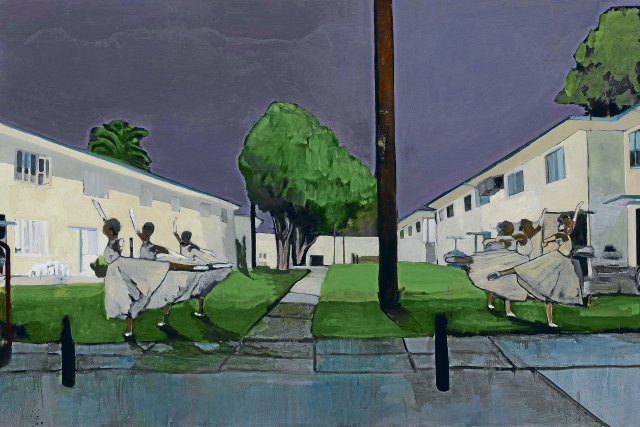

Noah Davis, “Pueblo del Rio: Arabesque,” oil on canvas, 2014

Photo: The Estate of Noah Davis. Courtesy The Estate of Noah Davis and David Zwirner

A single large square against a beige background. The painting that hangs here in the Kunsthaus “Das Minsk” in Potsdam and is the most abstract work by the US artist Noah Davis (1982–2015) is reminiscent of Kazimir Malevich. With his iconic painting “The Black Square” (first painted in 1915), the Russian suprematist wanted to “free art from the weight of things,” from any objectivity.

However, Davis’ square is not black like Malevich’s, but purple, and it is placed less squarely on the canvas. It is also even less of a square than the one whose sides, contrary to its name, are not all the same length. And is it even correct to speak of abstraction here in relation to Davis’ work? The picture, entitled »Nobody« (2008), shows the outline of the US state of Colorado. It is one of a series of three paintings in which Davis brought so-called swing states – US states in which both the Republicans and the Democrats have a good chance of winning the election – onto the canvas. Therefore it is only as abstract as maps are.

In 2008, the year the picture was taken, Barack Obama was elected as the first black president of the United States. The election in Colorado was close: Obama won it with 53.6 percent of the vote. As the accompanying text in the exhibition suggests, Davis’ picture was created before the election, which was undoubtedly of great personal importance for the artist. A black president meant representation. Davis was black himself; the lives of black Americans are the subject of his art. He himself said: »Race plays a role in that my characters are black. However, the images are anything but political. If I make a statement at all, it’s only to show black people in normal scenarios that drugs and guns have nothing to do with. Black people are rarely portrayed independently of civil rights issues or social problems in the USA.«

But is it even possible not to be political with art, especially with art whose protagonists belong to a disadvantaged minority in the country simply because of their skin color? The representation that Davis chooses is political because it breaks with the expectations of the viewer and thus makes them question their perception of the world. He sometimes shows his characters in seemingly surreal scenes and situations, the context of which he withholds from the viewer. If, for example, in a picture from the series “The Missing Link” (2013), a black man in a hunter’s hat examines his shotgun in a Monet-like spotted bush, then this may irritate some people because the country- and forest life in the USA seems to be reserved for white people. And in the painting “Pueblo del Rio: Arabesque” (2014), black ballerinas dancing gracefully in sync in the poverty and violence-ridden public housing estate of Pueblo del Rio in Los Angeles challenge our idea of where high culture has its place.

Davis evokes the surreal and dreamy not only through his choice of motifs, but also through his technique. He allows colors to blur into each other and sometimes run down the canvas in delicate streaks so that they lie on top of other colored areas. Sometimes they are applied thickly, sometimes thin and transparent.

Davis’ fascination with classics of art history is immediately apparent in many of his works: Some patterns – whether that of an armchair fabric or a background – look like they were created by Henri Matisse; In one painting – “Maury Mondrian” (2016) – an arrangement of colored rectangles can be seen in the background, which is clearly inspired by the compositions of the constructivist of the title. In the foreground: a black person, probably a child, who is apparently being grabbed by the shoulders by a white person whose head is covered by a petrol-colored area. The scene, which appears to take place on a stage – the image comes from a series by Davis on American reality TV – appears violent; The identity of the attacker remains hidden because of the petrol bar. Perhaps this picture not only contains a statement about the social structures of the USA, but also about art and its manifestations. Because abstract art – like Mondrian’s – despite its once revolutionary content, also has a obfuscating, anonymizing aspect.

Like the child’s face in “Maury Mondrian,” the faces of other black figures in Davis’ pictures are also painted rather roughly; in some cases the design of the sensory organs is missing, and some are even distorted into a grimace in the Francis Bacon manner. Doesn’t Davis take away his characters’ individuality, make them interchangeable, so to speak, and thereby cement the status assigned to them by the ruling class? That would one Reading. However, Davis was not so much concerned with individual people and fates, but with structures, with life in black communities, especially in his adopted home of Los Angeles. And when Davis, for example, only depicts the faces of his characters in his reality TV series, it can also be interpreted as meaning that he is hiding them from the voyeuristic gaze of a sensation-seeking audience.

Davis himself came from a wealthy, educated family. He studied painting in New York, but dropped out after a few semesters and moved to LA in 2004, where he worked as an artist from then on. There, in the historically poor Arlington Heights district inhabited primarily by blacks and Latinos, he founded the “Underground Museum” with his wife and brother in 2012. Because of the high crime rates in Arlington Heights, however, there were no museums or collectors willing to lend their works to the “Underground Museum.” So in 2013, Davis showed the show “Imitation of Wealth,” for which he simply recreated, painted, or “purchased” iconic works of art as ready-mades. Three of these exhibits are on display at the Minsk Art House: a bottle stand based on Marchel Duchamp, a vacuum cleaner enclosed in Plexiglas based on Jeff Koons and a gravel mirror corner based on Robert Smithson.

Ironically, it is precisely these many references to a largely “white” art historical canon that made Davis himself a star. Posthumously, he died of cancer at the age of 32 and is considered one of the most important contemporary American artists. This first institutional exhibition will help him become more well-known in this country.

“Noah Davis”, until January 5, 2025, Kunsthaus Das Minsk, Potsdam. Then seen in London and Los Angeles.

Subscribe to the “nd”

Being left is complicated.

We keep track!

With our digital promotional subscription you can read all issues of »nd« digitally (nd.App or nd.Epaper) for little money at home or on the go.

Subscribe now!