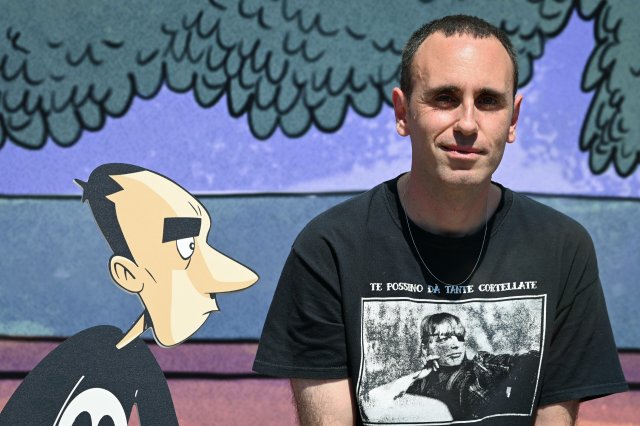

Photo: Imago/ZUMA Wire/Marilla Sicilia

What impression does Berlin make on you? Do you think the city can be compared to Rome?

My first impression is that everything works better here and the city is less neglected than Rome. But I also mainly saw Kreuzberg and the tourist areas. To see if the cities are similar to each other, I would have to get to know the outskirts.

In any case, the people here have a reputation for expressing themselves very directly or even rudely, which is also typical for Rome. Your district of Rebibbia plays a big role in you and your work, and you speak with a Roman accent. On the Italian left there seems to be no contradiction between a very strong local roots and radical political convictions. Where does it come from?

Well, I actually only learned Roman when I became politically active. This is what people said at political meetings. Especially those who were older than me, who came from workers’ autonomy. Because my mother is French, I spoke more standard Italian at home. Paradoxically, I speak Roman more in public, in front of an audience, in a political context, and less in private.

Interview

Niccolò Caranti

Zero limestone, real name Michele Rech, was born in 1983 in Arezzo, Italy. He first became known as a blogger and since 2011 through his autobiographical everyday stories.

In Germany, the radical left is quite academic, and it is more typical for people to get rid of their regional accents when they do politics.

The radical left in Italy has never been so academic. But all of that is changing under the influence of social media. Politicization no longer takes place primarily on site, in the city districts and in direct exchange with older comrades, but on the Internet, under the influence of political influencers. On the one hand, the language is standardized, and on the other hand, contact with one’s own territory is lost.

Furthermore, I have the impression that places play an important role in the Italian left: it is always about a place that needs to be defended, be it the local autonomous cultural center, or the Susa Valley, through which a high-speed line is to be built , or be it Rojava. Why is the Italian left so “geographically” oriented and less economically oriented?

The reasons for this lie in the history of the Italian left. In the 1980s, after the failure of the armed struggle, all these politically active people returned to the city districts. Due to the strong state repression, people have limited themselves very much to a local perspective: “If we can’t fight the state with weapons in our hands, then at least we’ll occupy a local house and make it a place according to our ideas functions. If we can’t change the country as a whole, then let’s at least try to change this neighborhood. All of these individual projects can also unite and support each other, but the prerequisite for this is strong local roots. And that is the attitude with which my generation also grew up – perhaps the last. But unfortunately this seems to be something that the new politically active generation has lost. For example, I notice that, unlike my generation, young activists neglect the physical spaces of the left. We have occupied houses and are involved in autonomous centers because we need a place where we can organize ourselves, paint banners, celebrate festivals and so on. But the movements, which consist of very young people, have no need for this, which is difficult for me to understand: if you don’t have a concrete place where “normal” people can find you, you lose contact with them.

But don’t you also lose perspective on other political goals, on the class struggle, when you concentrate so much on defending alternative places?

This limitation to local projects is not so much a political goal in itself, but simply a consequence of the weakness of the left. When we were stronger, we were able to pursue broader goals and fight for them credibly.

The defense of certain places also plays a role for the left on an international level. But are there also limits to “anti-colonial” solidarity?

I can only speak about this for myself, and not for the left as a whole. The contact with the Kurdish liberation struggle had a strong influence on me. There are countless injustices in the world and countless liberation projects to show solidarity with at the international level. But in order to really work together, I think we need a common language, a common political horizon. This does not necessarily mean exact agreement on all policy issues, but it does mean a common direction in which to go. And I didn’t find anything like that anywhere for years until I came into contact with the Kurdish cause. Rojava seems to me to be a political project in which we can participate and from which we can learn a lot politically. That’s why I’m committed to it.

Photo: Avant-Verlag/Zerocalcare

In this interview we mainly talked about politics and it seems to me that you are in Italy the He has become a “political intellectual” who is asked in interviews about all sorts of political topics. How are you doing in this role?

I see myself only as a speaker for a collectivity. I only want to talk about causes that I really pursue and in which I am involved with many others. This means that I go to the plenary session once a week, I engage with people who know more than me, and I can then advocate for the collectively developed positions in front of a wide audience. But when I’m asked about things that I don’t really think about, it makes me uncomfortable. Opinions that I form spontaneously are not of interest to the general public and can also be determined by prejudices. These are things that I might say to a friend in the bar, but they are worthless to an audience of millions. What I say publicly must be a collectively developed position. And it’s hard to make some journalists understand that, but also some activists. A simple example: climate change. I believe that climate change exists, that the fight against it is very important and I am very happy that there are many young people who are leading this fight. I also like going to a demonstration against climate change. But because this topic didn’t play a role during my politicization in the 90s and noughties, I don’t have that background. At 40 years old and with my workload, I can’t regularly get involved in this fight and go to further plenary sessions. That’s why I don’t think I can speak for this issue. I simply don’t know enough about it, and if I talk to a hostile journalist and reveal my lack of expertise, it’s not just me who becomes “brutta figura” but the entire movement.

On Instagram, you announce hour-long signing sessions where you also create personalized drawings. It seems like assembly line work and seems to be putting a lot of strain on you. What do you as a working person say about your working conditions?

As a worker, I am very privileged because my work is paid much better than that of the people around me. And the work is also less grueling than on a construction site or in a factory. I am exploited in the sense that the value my work generates is much greater than the payment I receive for it. That’s just capitalism, but I’m pretty privileged in this system. However, due to feelings of personal guilt, I subject myself to torment that no one demands of me in the work context. For psychological reasons, I just don’t want to be reprimanded like: “I came from another city for this reading, but you only signed for an hour. Now that you’re making a lot of money, you don’t care about your audience.”

They would have to strike.

But this strike would not be directed against my bosses. They are rather annoyed by the constant signing because it makes the events drag on. So I would strike my readers, and I can’t do that – unfortunately.

Zerocalcare recently published the comic report “No sleep till Shingal” in German about the living conditions of the Yazidi population and their efforts to build democratic federalism based on the Kurdish model after the attempted genocide by IS.

Zerocalcare: »No sleep till Shingal«. Avant-Verlag, 200 S, Hardcover, 28 €.

Become a member of the nd.Genossenschaft!

Since January 1, 2022, the »nd« will be published as an independent left-wing newspaper owned by the staff and readers. Be there and support media diversity and visible left-wing positions as a cooperative member. Fill out the membership form now.

More information on www.dasnd.de/genossenschaft

sbobet akun demo slot link sbobet judi bola