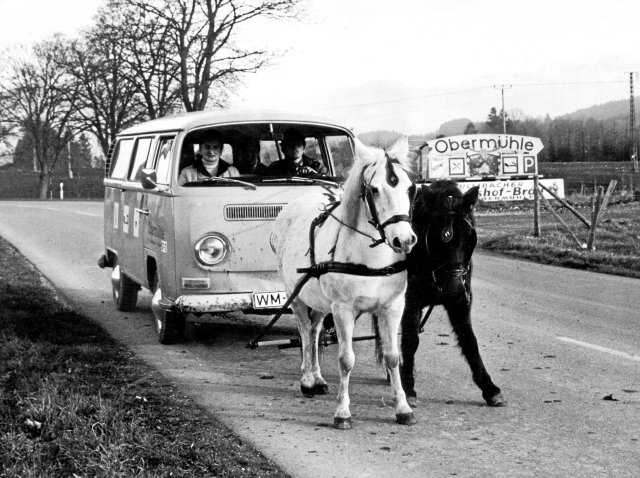

Back to two horsepower: In the course of the oil crisis in 1973, the promise turned out to grow further as an illusion.

Foto: IMAGO/United Archives Keystone

It is an irony of history, ”wrote the Marxist historian Eric Hobsbawm in 1994 in his description of the history of the 20th century as“ Age of Extreme ”,“ that the “real socialist ‘businesses of Europe, the Soviet Union and parts of the third world should become the real victims of the capitalist global economic crisis according to the golden age”. Because while these had come into severe crises, “the” developed market economies “could have survived the difficult years, at least until the early 1990s, with a few shocks, but without problems threatening existence”. Hobsbawm thus formulated a very heretical thoughts for a Marxist, most followers of the old from Trier assumed that the cyclically recurring crises of capitalism would lead to strengthening his opponents up to his fall. That it turned out differently, which Hobsbawm attributed to the “combination of incompetence and corruption” of the Soviet nomenclature on just a few pages, this thought has hardly been followed.

The American historian Felix Bartel has now adopted this strange dialectic of time runs, although without reference to the Hobsbawm, who died in 2012. In his study “Broken Promise”, he analyzes how the crisis symptoms of the early 1970s conditioned both the rise of neoliberalism and the end of state socialism.

Integration through mass consumption

Bartel’s starting point forms 1973: the oil price shock, which temporarily quadrupled the costs of the most important lubricant in industrial capital, and the end of the Bretton-Woods system of the stable exchange rates have brought the crisis moments of the world economics to be a long time. And this in east and west alike, because on both sides of the Iron Curtain, the growth of productivity had slowly slowed down. What was the profit clamp in capitalism was a reduced investment fund. Together, these aspects for Bartel represent “the defining feature of a privatized cold war”: From now on, the nation states have become dependent on loans in order to “continue to finance their foreign and domestic politics and to be able to delay the shocks of the oil crisis”.

As a result, this meant nothing less than a paradigmatic change in terms of the internal integration performance of the combatants in East and West. Until then, the Cold War was also “a competition between two systems, the governments of which competed with social promises that were guaranteed by unprecedented economic growth,” as Bartel explains. And this was anything but a secret: On the occasion of the visit to the American national exhibition in Moscow by the then US Vice President Richard Nixon, there was an exchange of blows that all over the world and Nikita Khrushchev. While Nixon in the face of the mass consumption shown made in USAwho actually expressed incredulous astonishment in the Soviet Union that the standard of American workers, including televisions, washing machines and cars, praised the Soviet Secretary General that the first socialist state in the world would reach the US standard of living within seven years. “If we pass you by,” said Khrushchev the world, “then we wave friendly, and if you want, we stop and invite you to follow”.

“The Cold War began to give promise as a race, but ended up being a race to break promises.”

Fritz Bartel historian

As is well known, nothing came of it. It is unclear whether Khrushchev has ever believed in the closure of the gigantic productivity gap compared to the developed capitalist states. At the latest from the mid -1970s, however, the crisis, which initially suffered the folk democracies in Hungary and Poland and then attacked all states, which was interrupted in the Council for Mutual Wirtschaftshilfe (RGW), could hardly be denied. The economy only progressed with the “speed of an exhausted ox” (Hobsbawm). The RGW countries recorded less than one percent economic growth on the average of the 1970s. And even this, as Bartel proves, was increasingly financed by loans of Western financial institutions that gave governments in Warsaw, Budapest, East Berlin, Prague and even in Moscow at least some room for maneuver.

Extended grace period

However, on the other hand, things went anything but round on the other side of the demarcation line. In 1974 the western industrialized countries experienced the first major recession after the long post -war boom. Unemployment, which was practically unknown to that generation of those born after 1929, rose to 5.5 percent in the OECD countries this year, and even almost nine percent in the United States. However, an ace in Washington still had its sleeves: In contrast to the unconvertable currencies of the Eastern Bloc, the USA, according to Bartel, could have extended its “grace period”, since “the United States retained its lax monetary policy in the 1970s” and the dollar was still considered trustworthy.

At the latest, however, the “escape from the dollar” and the following inflation made it clear here at the end of the 1970s that it could not go on. It was the shock from 1979 named after the central bank boss Paul Volcker, who changed a lot. Interest rates of over 20 percent docked the loan volume dramatically and, celebrated by the bosses and the neoclassical economists that they devalue, released a whole wave of social attacks on class compromises in the capitalist states.

Victory of capital

“The fact that America had finally decided to cope with their own crisis through the termination of social promises,” concludes Bartel, “, in view of the central role of the dollar for the global economy, meant that the rest of the world – including the communist states in the Eastern Bloc – remained no choice but to take the same course”. In essence, the currency crises in the West sprang up the same causes as the debt crises in the Eastern Bloc countries. Here is a new paradigm: «The Cold War began as a race to promise givebut ended as a race to promise to break», According to the central thesis of the teacher and researcher at the Texas A&M University, who also gave the study the name.

Nd.Diewoche – Our weekly newsletter

With our weekly newsletter . We’re Doing Look at the most important topics of the week and read them Highlights our Saturday edition on Friday. Get the free subscription here.

Bartel traces the subsequent triumphal march of neoliberalism in the OECD countries as well as the reform efforts in state socialism and their final failure using various examples. This makes up the great value of the study towards subjectivist perspectives, which traces the “Social Current Revolution” (Hobsbawm) of neoliberalism into the political and social power of entrepreneurs or economists according to Art Milton Friedmans and his Chicago Boys. Bartel, on the other hand, has a convincing manner that this has long been a well -known “capitalist vision” to “cope with the” real challenges for governments in East and West “.

The fact that this was better in the west was initially due to the better standard of living in the old capitalist centers owed in higher productivity. In addition, according to Bartel, the imposition – which also included the financing of the gigantic military devices, which lacked funds for social policies – could be adapted to well -known ideological patterns. On the other hand, the commitment to communism “no longer made any sense in such an era of social incisions”. And contrary to the authoritarian Eastern Bloc countries, the democratic constitution of the states in the West also proved to be more adaptable to “neutralize resistance to the government”.

The SED financial expert Günter Ehrenperger, for example, drew attention to how difficult this dilemma seemed to be. “If we want to get out of this situation,” he said in the central committee, “we have to consume at least 15 years less than we produce”. However, this can hardly be conveyed to the workers of the GDR, as the uprisings in Poland have proven again and again since 1970. A socialism that had to be the “servant of two gentlemen: the people and the markets” (Bartel) finally lost all the rest of legitimation, which he might have enjoyed in parts of the population. “The end of the Cold War”, according to Bartel’s depressing conclusion, was “the moment when the people’s power reached its peak – and was also overcome”. The logic of capital had won globally. In particular, the study of Bartels is likely to be extremely useful to understand this “Triumph (s) of the broken promises” of the broken promises.

Fritz Bartel: Broken promise. The end of the Cold War and the rise of neoliberalism. Hamburger Edition, 440 pages, born, 40 €.

judi bola judi bola link sbobet link sbobet