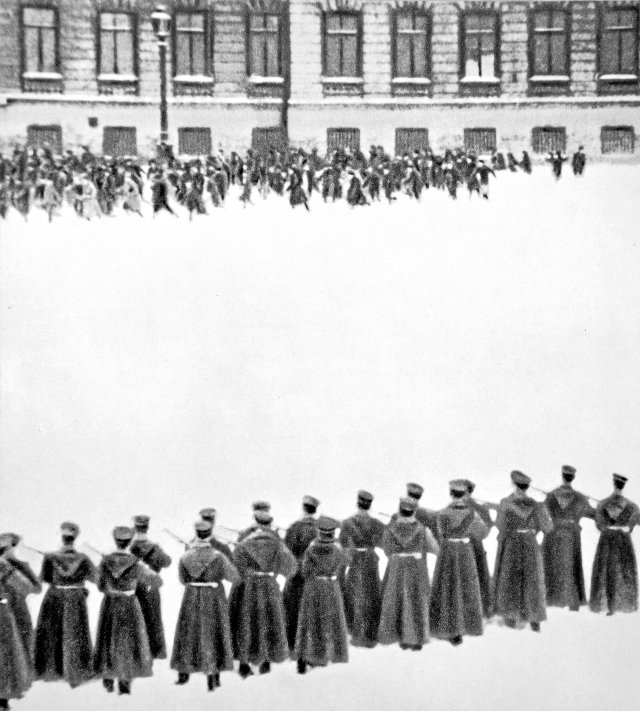

Gap between desire and reality: The uprising for better working conditions ends in violence. Scene from a silent film about “Petersburg Bloody Sunday” in 1905.

Foto: imago/United Archives International

Even before reunification, in 1990, Reclam Leipzig published an anthology with texts by Thomas Brasch: “Three wishes, said the golem.” In 1976, Brasch left the GDR, half voluntarily, half under pressure, which left some bitterness on both sides. The anthology concluded a process of rehabilitation for the author that had already begun tentatively over the years. Of course, the book appeared too late to have any effect in the GDR – and above all for the GDR. If it had been published just a year earlier, the title alone would have caused a scandal.

Brasch’s poem in the title contains a wish for annihilation, speaks of death and the desolate afterlife, nothing that would have fit into the forced-optimistic image of state socialism. »Three wishes, said the Golem«, well, the first: »Home with the dead, I answered, / across the Warsaw Bridge in the afternoon. / When the black moon rises next to the sun / I will show them the gap in their republic .” The second: “On an atomic bomb over the Frankfurt train station, I answered, / how quiet it is here in seventh heaven. / Only the wind and the stench of democracy: / I fall down laughing in the crowd.” And the third : “Living in a destroyed house, I answered, / alone in a devastated landscape, / scratched letters into broken bricks / to my dead relatives.” Thomas Brasch was the son of refugee Jews, born in exile in England in 1945.

nd.DieWoche – our weekly newsletter

With our weekly newsletter nd.DieWoche look at the most important topics of the week and read them Highlights our Saturday edition on Friday. Get your free subscription here.

The fact that wishes are nothing harmless, that something is stored in them that speaks of trauma, injuries, historical injustice and calls into question the false peace of the present is openly expressed in “Three Wishes, Said the Golem”. Also the desperation that comes with it. Because Agent of Wishes is a legendary Jewish mythological figure. The golem is a killing machine made of clay that has no will of its own but only listens to its creator. The contrast to a working class that would become aware of its situation and intervene thoughtfully and powerfully in the devastating course of events in order to change it for the better could not be greater. The anarchist Thomas Brasch no longer wanted to talk about this working class in 1980, the year in which the poem was first published.

The terrible wishes

Wishes can be sardonic and refer to the loneliness or lostness of those who express them. They can also be frightening. The author can no longer remember the originator of the following story, it comes from a young adult book and has caused horror for years: A serving spirit grants a married couple three wishes – usually there are three wishes. The first thing you want is material security and prosperity. A little later, the general counsel of the company where her son works on the assembly line rings the doorbell. Her son was crushed in an accident at work and the company is prepared to pay a large sum of compensation. The woman, half mad with grief, expresses the second wish – that the son return. At night the two old people hear someone shuffling up the stairs. The man has an idea of what the person coming will look like. All that remains is the last wish that the son disappear. In the end they were left with nothing. The naivety, even innocence, of wishing turns into its opposite. Hence the horror.

The horror points to the social character of the desire. Because the wish only develops when confronted with reality; it is not enough to express it, it must be implemented. And that is the moment when the wish no longer concerns those wishing alone, but is delegated to authorities who interpret the wish according to their standards. In a world where those who desire are usually those who have the least (that’s why they desire something) because they work for the wealth of others, their desires are adjusted in such a way that they do not break this relationship, but rather reliably confirm and maintain it.

If you want the welfare state, you get a bureaucratic monster that uses welfare to control and discipline those who depend on it. Welfare is a means of strengthening the unemployed, the industrial reserve army, which must keep itself fit when it is needed again in the offices, warehouses and factories during the next upswing. Or it is a means of keeping wages low: when people remain dependent on welfare state benefits because their job does not pay enough wages. Those who want freedom, on the other hand, get deregulation, privatization, public spaces in which the law of the strongest applies. “Our wishes are anticipations of the abilities that lie within us, harbingers of what we will be able to achieve,” says Goethe. In the society of the capitalist mode of production, in which everyone’s abilities are directly linked to his or her labor, this is a threat. What we will be able to achieve will be determined by the level of exploitation.

You don’t have to aim so high, the negative dialectic of the wish proves itself in all its evil in everyday life: If you wish for a white Christmas, you get fatal car accidents on icy roads and homeless people frozen to death on the side of the road. Anyone who, after generations of poverty, wants a meat meal every day will have a climate catastrophe and, first of all, heart disease. Anyone who wants the German national soccer team to be European champions will get the nationalistic frenzy after victory.

So no more wishes at all?!

But there are a lot of wishes that are really completely innocent, one might object, because there is simply no authority that can implement them. Let’s stick with football and say: Union Berlin should make it into the Champions League again! Wishes of this kind are perhaps not meant to be realized (it is well known that smaller football clubs that have surprising success cannot cope with the stress of playing in multiple competitions and end up playing against relegation the following season), but rather they create a nostalgic world, the illusion of a realm that does not come into contact with the dust and dirt of the actual world. In this case, the negative dialectic of desire consists in escapism, which only reinforces the prevailing reality. Because it is she who remains unassailable, immovable, unchangeable.

So no more wishes at all?! “The time for demands is over” is the subtitle of an anthology published in 2009 about the unrest in the French banlieues, which has not subsided to this day. The demand is the desire that has become political, its translation into the language of party programs and government coalitions. When the time for demands is over, it means that the state and its organs are no longer addressees, that politics is no longer a social field of compromises – always to the detriment of the workers, the precarious and the subaltern. Rather, they are an obstacle that needs to be overcome without anyone asking permission.

Then, as one would have said fifty years ago, the time of autonomy begins. But just because one claims that the time for demands is over does not mean that the demands and desires have disappeared. The desire for social security, for working relationships that don’t destroy you, for good education for your children: all of this still exists. The “autonomous” class struggle will also have to be oriented towards these wishes – sometimes more, sometimes less consciously. The leap into a world of unbridled radicalism, when you stop demanding and only rely on yourself, belongs to the category of unrealistic desires that produce illusions. In reality, people’s imaginations and thus the realm of their wishes and longings remain chained to what capitalism sets as the norm with its consumer worlds, promises of luxury and preachers of salvation.

Paying attention to your wishes – even your own – no matter how small, should therefore be the top priority for all activists, militants and radicals. Because sometimes the wishes come into conflict with the authorities, which are in a deeper crisis than we imagine and are no longer able to melt them into a compliant program. That Sunday in January 1905 in Petersburg was legendary when 150,000 poor people made their way to the Winter Palace, carrying pictures of the Tsar in front of them and wishing nothing more than for the good father to grant their requests for more humane factory legislation. But he panicked out of sheer affection and had the demonstration shot down. It sparked the first Russian revolution. Wishing hadn’t helped back then either – but denying wishes didn’t help either.

Become a member of the nd.Genossenschaft!

Since January 1, 2022, the »nd« will be published as an independent left-wing newspaper owned by the staff and readers. Be there and support media diversity and visible left-wing positions as a cooperative member. Fill out the membership form now.

More information on www.dasnd.de/genossenschaft