Catholic, communist, satellite city boy and gay esthete: Pier Paolo Pasolini was a man of contrasts.

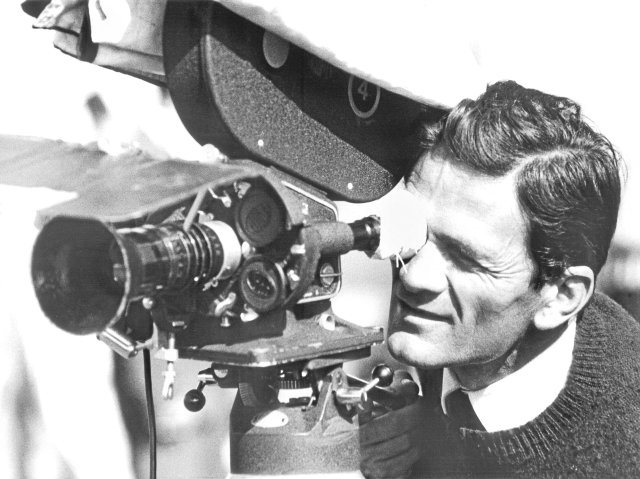

Photo: dpa

The premises of the nbk (Neuer Berliner Kunstverein) in Berlin-Mitte are not particularly spacious. The wall appears all the more powerful when entering the gallery, which almost overwhelms you with the list of the countless legal proceedings that were initiated against Pier Paolo Pasolini over the course of his work. Italian society and its state tried to fight the communist Catholics and self-professed gays with all the means of the rule of law and the tabloid press. His cinematic and literary work, in which he attempted to amalgamate Gramscian folk culture, Catholic symbolism, criticism of late capitalism and a different form of sexuality, was not particularly warmly received by the authorities and their petty-bourgeois supporters of post-war Italy. In an allusion to these conditions and to Pasolini’s film “Porcile” (1969), the exhibition is named with the same film title – “Pig Stables”.

A wealth of sound and film clips, contemporary newspaper articles and interview fragments attempt to get to the bottom of Pasolini’s extremely provocative and contradictory life and work. A communist who opposes the legalization of abortion because it conflicts with his view of the sanctity of life. A gay man who is skeptical about the liberalization of sexual morality as a gateway for the new disciplines and appeals of consumerism. An anti-nationalist who enthusiastically integrates the – alleged – customs and traditions of the rural, semi-feudal masses into his art, on the basis of which the rejected bourgeois nation state can emerge in the first place. A boy from the Roman satellite towns, the “Borgate”, which house the small-time crooks, the prostitutes and the left out, and at the same time a man of style, beauty and so-called high culture. A bon vivant who believes he is in a permanent concentration camp. All these opposites are conveyed in Pasolini. A lot of things are certainly worthy of criticism – but not in the sense that they have to be absolutely rejected. Rather, Pasolini offers us material with which we can try to penetrate an object in a reflective manner. His provocations today perhaps no longer cause repulsion and shock as they did in the 60s and 70s, but have become real challenges for criticism. What was probably most shocking about his work at the time, the frivolous, unbridled and even violent sexuality, would no longer attract anyone from behind the stove today. Over time and liberalization, sexuality in all its facets has been integrated into capitalist society, at least in the West. Pasolini had very sensitive sensors for this process relatively early on. Today, criticism could be formulated without drifting into conservatism.

nd.DieWoche – our weekly newsletter

With our weekly newsletter nd.DieWoche look at the most important topics of the week and read them Highlights our Saturday edition on Friday. Get your free subscription here.

The suddenly interspersed props and costumes from Pasolini’s films have an astonishing effect in the exhibition, for example a helmet from “Porcile” or a doublet from “Medea” (1969). If the other exhibits are located in the image and written area and can therefore be processed mentally, the focus on the physicality of Pasolini’s work promised by the exhibition can be experienced here. Of course the pieces cannot be touched, but their materiality is still strangely tangible. Aspects that often characterize Pasolini’s films and that are not entirely understandable in the short excerpts shown. The exhibition manages so brilliantly to convey to visitors the mediation of mind and body, the unity of their contradiction, which is explored in Pasolini’s oeuvre.

Unfortunately, the chronological conception of the show forces it to end with Pasolini’s last film, “Salò o le 120 giornate di Sodoma” (1975). One can be tempted here to interpret Pasolini’s work in terms of this last film. Based on de Sade’s “The 120 Days of Sodom”, young people in the Republic of Salò, a fascist puppet state of the Third Reich in northern Italy at the end of the Second World War, are kidnapped by representatives of the state, church, politics, law and nobility and taken to prison Most brutally humiliated, tormented and tortured. But looking at Pasolini from this film, as is sometimes done, doesn’t quite do him justice. In his poetry, his films and his political-aesthetic writings, which can be seen in fragments, Pasolini certainly identifies himself as an artist of the body. But for him this is always conflicting and ambivalent, not a pure effect of state and socio-economic institutions and discourses. Pasolini’s films and the props in particular show the body’s own logic, a sensuality that is more than just a construction of social power. This means that the body is not just a workable mass. Pasolini’s films show this. The form of the exhibition somewhat undermines its own claim here. Nevertheless, it is recommended to anyone who wants to get an overview of Pasolini’s disparate thinking and work and the mess we call society.

»Pier Paolo Pasolini. Porcili”, until November 10th, nbk / Neuer Berliner Kunstverein

Become a member of the nd.Genossenschaft!

Since January 1, 2022, the »nd« will be published as an independent left-wing newspaper owned by the staff and readers. Be there and support media diversity and visible left-wing positions as a cooperative member. Fill out the membership form now.

More information on www.dasnd.de/genossenschaft

sbobet judi bola sbobet judi bola online