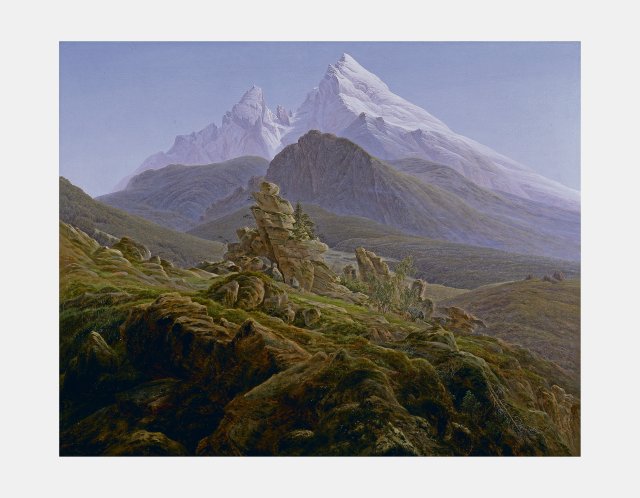

Caspar David Friedrich, The Watzmann, 1824/25, oil on canvas, 135 x 170 cm

Photo: Berlin State Museums, National Gallery/ Loan from DekaBank / Photographer: Andres Kilger

On the front wall in the large hall of the Alte Nationalgalerie, the iconic pair of images “Monk by the Sea” and “Abbey in the Eichwald” (both 1809/10) immediately captivate: the monk, standing in emotional shock in front of nature, but at the same time sea and Defying heaven. If you can see the renegade monk here, whose old faith has fallen apart, in the other picture the monks do not seem to risk a clear view of the sky. The flickering branches of the oak trees that surround the Gothic ruin and the hazy moonlight in the background are set against the steady rhythm of the funeral procession.

Both pictures, which speak of the inscrutability of nature, were first shown by Caspar David Friedrich at the academy exhibition in Berlin in 1810 – and last but not least, they were designed by the Prussian King Friedrich Wilhelm III. acquired, made him famous as the creator of romantic landscape art, in which the sensual and the symbolic are combined.

In 1906, the Berlin National Gallery had already contributed to the rediscovery of the painter Friedrich, who was largely forgotten at the time, with its “German Centenary Exhibition”. Now – in the 250th year of his birth – a large retrospective of the most modern of the Romantics is taking place in the Alte Nationalgalerie with more than 120 works. The three museums in Hamburg, Berlin and Dresden, which have the largest holdings of Friedrich’s complete works in the world, have coordinated their own thematic anniversary exhibitions – the one in Hamburg closed on April 1st and reached a record of 335,000 visitors – so that they can exchange their masterpieces with one another, provided their condition does not prove to be too fragile.

In Berlin, the theme of people and landscape in Friedrich’s work is dedicated and the focus is on his famous pairs of images and cyclical landscape designs. The latest research results on Friedrich’s painting techniques can also be demonstrated. In his process of blending natural and human life in a cyclical manner and charging them symbolically, the painter was able to combine feeling and meaning and create a new symbolic art with increased emotional impact.

His vision only unfolds in the image that he sees inside and that corresponds to his feelings. Tree and forest, rock and path, cave and gate, ruin and grave, moon and clouds, land and sea, coast and mountains, day and night, life and death – symbolically they become symbols and hieroglyphs in which the intangible becomes understandable should be done. The vertical in front of a low-lying horizon line, the transitory movement of the clouds, the individual object in a barren surrounding space, which challenge interpretations simply because of its isolation, these are just a few of the composites of Friedrich’s visual language.

Sometimes the draftsman seems to have constructed the group of fir trees like a Gothic architecture. Then again the sky stands there as an imaginary wall, non-spatial, of immeasurable, transparent tension. Reality becomes so concentrated that it spills over into a field of meaning that lies beyond the visual. Deep perspectives are opened and obscured. The world dissolves into perspectives, into observers and observers of the observer. And Friedrich cannot avoid the inner images any more than he can avoid the dreams.

The back figure in “Woman at the Window” (1822) depicts Caroline, the painter’s wife, looking out of the dark confines of the interior through the window cutout into the light outside. In contrast, the contours of “Wanderer in the Sea of Fog” (around 1818) are reflected in the rock formations shrouded in fog, so that one could imagine the landscape even without figures. “Chalk Cliffs on Rügen” (around 1818), created in connection with Friedrich’s honeymoon, shows three figures in different attitudes to life: the woman dressed in red, probably her wife Caroline, dedicates herself to the nature that opens up to her with undisguised joy of life; The middle figure may be Friedrich himself, kneeling with his head bare and looking into the abyss, while the male figure on the right is standing with his arms crossed – an alter ego of the painter? – looks over the abyss into the distance to the sea.

Accompanying this picture is “The Stages of Life” (around 1835), in which Friedrich depicts himself with his family members. The five ships are assigned to the five people – the figure on the back of the old man, the painter himself, the large ship returning from an ocean voyage, which has already retracted its sails, is interpreted as Frederick’s life ship. Many of his late pictures are melancholic allegories of transience in the sense of a memento mori.

With the “Watzmann” (1824/25) as well as with the “Eismeer” (1823/24), Friedrich depicted areas that he had never seen. They are visionary symbols of divine majesty and aloofness. While in the foreground the rocky cliffs with their spruce and pine trees appear to be in motion in brightness and darkness, behind them a huge mountain range rises in eternal calm.

Friedrich makes seeing, looking, reflecting the theme of his paintings and drawings. And we should feel called upon to do the same.

“Caspar David Friedrich – Infinite Landscapes”, Alte Nationalgalerie, Berlin State Museums, until August 4th.

Become a member of the nd.Genossenschaft!

Since January 1, 2022, the »nd« will be published as an independent left-wing newspaper owned by the staff and readers. Be there and support media diversity and visible left-wing positions as a cooperative member. Fill out the membership form now.

More information on www.dasnd.de/genossenschaft

sbobet88 judi bola pragmatic play judi bola