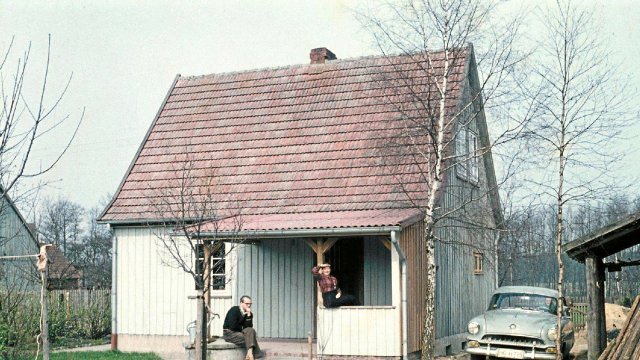

With the Opel captain of the educator and friend Wilhelm Michels, who first visited the Schmidts in April 1959 in Bargfeld

Photo: © Archive of the Arno Schmidt Foundation/Suhrkamp-Verlag

Already on the first evening of the “Arno-Schmidt-Days” held in the Berlin Brecht-Haus, which dealt with some of Schmidt’s early stories from the late 1940s and early 1950s (“Die Umsiedler”, “Black Spiegel”, “From the Life of a Faun”), you are united in one thing on the podium: If in the stories of Arno Schmidt (1914–1979) The male protagonist speaks when the manplain end of the first person is lecture on the deployed world of world and the discarded nature of humans always speaks unmistakably.

In order to reaffirm this observation, the writer Gerhard Henschel quoted the former “Merkur” editor Kurt Scheel, who in turn found 23 years ago in the “taz” that we, the readers, in Arno Schmidt’s “knowledgeable” heroes and narrators “to see the age ego of the author”. In the end, it is not always partially separated where the figure speech ends and where the Schmidt speech begins. This will be clearly in the conversations of the Schmidt heroes “About God, the world and above all the literature, where steep theses and bizarre judgments about famous and less famous writers are apodictically announced”.

“Anyone who occasionally feels a facility to become a know -it -all and the Dünkelmann, so if you are a sinner every time, you will recognize yourself from Schmidt and in Schmidt.”

Kurt Scheel

But also in the “contempt for people – either the others are stupid or evil, or they stink, but it is enough that they are simply there to attract the narrator’s reluctance”. Scheel asks: »Was there another German writer in the 20th century who brought up the Kotzbrockige of his heroes with such accuracy, sensitivity and words of words and made them tolerable or even fascinating and also the rest of the world? Anyone who occasionally feels a facility for a know -it -all and the Dünkelmann, so if you are a sinner all over, you will recognize yourself at Schmidt and in Schmidt, this puzzle monument, perhaps the largest German tongue after 1945. «

Despite all the comedy, the Schmidt’s prose still harbors-even the most patient-even the constant “vertical speak” (Ulrike Draesner) of the auttorial narrator or the “hammering tone of instruction” (Gustav Seibt), whom Schmidt’s heroes or anti-heroes show, fall on the nerves.

The preoccupation with the bizarre personality Arno Schmidts, the eternal decision -making and misanthropes, may have been in the foreground, but there were no questions of the linguistic form, even if it was not necessarily new. The writer Ulrike Draesner, for example, recalled that Schmidt, on the one hand, had linked to expressionism and “not contaminated, not worn -out,” of the literary modernism that was not contaminated, but on the other hand it was also unknown. The most striking shows this at the “sexualized look at women”, which “was common at this time” among the almost exclusively male writers of the era.

The playwright Enis Maci, born in 1993, who had probably been invited as a representative of a recent generation of authors, made the contradiction between the conservative gender understanding of gender roles in Schmidt’s prose and the very modern linguistic procedures that were used for their time: The content was “Lüneburg Heath 1950”, whereas “not Lüneburg Heide 1950”. Maci’s brief characterization of the male main character in Schmidt’s 1953 novel “The life of a Faun” was narrowly: “Heinrich Düring is not in the mood for the Nazis and also no in his wife, but still more in the Nazis.”

Nd.Diewoche – Our weekly newsletter

With our weekly newsletter Organization Look at the most important topics of the week and read them Highlights our Saturday edition on Friday. Get the free subscription here.

Arno Schmidt never made a secret of the fact that he saw himself as the great poet genius and his wife Alice as a companion, assistant and secretary. The fact that Alice actually played a much more important role than that of the mere assistant was discussed on the second evening when Susanne Fischer from the Arno-Schmidt Foundation and the writer Karen Duve read selected passages from Alice’s diaries. “She was his employee in a variety of ways,” Fischer stated. »She typed translations, led publishing negotiations and did correspondence. Her job was the operation of the outside world, especially while ‘Mingus’s dream’ was created. ”But in her daily records and emergency, she developed something like her own narrative voice over time.

The suggestion that his wife should write a diary was originally from Arno. In the beginning, it should of course be used to document your life as a writer. However, after a while, Alice, mostly developed notes about the everyday life of the couple in the 1950s. Of course there are places like those in which she finds that Arno is “wise and gifted and gifted”, but there are also many purring and anecdotes like the one in which she reproduces in great detail and punchy, what her husband told her when he left from an “linked Catholic court” who had kept knowing his prose as “dirt and trash”. (Schmidt was heard in August 1955 because one of his stories had a lawsuit about “pornography”.)

Alice Schmidt’s “great merit” would be that “she gave the everyday life of work and life team Schmidt a face”, says Fischer.

In the end, the question of who, almost 50 years after Arno Schmidt’s death, must actually remain open. With an episode that Gerhard Henschel told on the opening evening, he at least gave an indication of which milieus the readership of Schmidt’s readership. Henschel reported that he once met a “retired forest”, which he pointed out in a conversation at Schmidt’s work. Whereupon the man was apparently awakened. Little by little the Forstrat enthusiastically read the Schmidts work, including its large novel »Zettel’s dream«. “Twelve times,” said the enthusiastic pensioner, he had been pilgrimed to Bargfeld since then, into the tiny Heidedorf, in which the couple Alice and Arno Schmidt had lived withdrawn since 1958. The last time he, Henschel, who had met him, the forest, was just about to measure Schmidt’s private reading desk with the intention of recreating it at home.