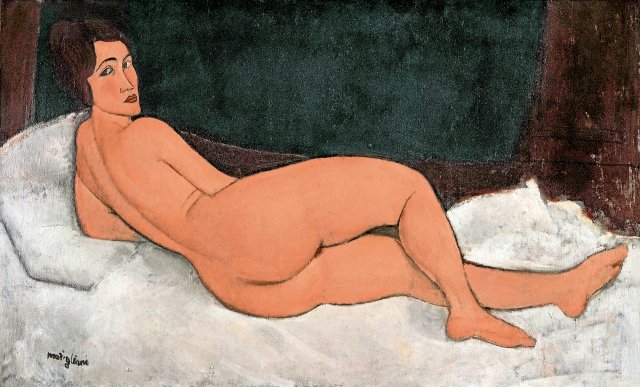

This painting was created in 1917, when Modigliani’s art caused a scandal: “Female nude lying on her side”, oil on canvas

Foto: Photo © The Courtauld / Bridgeman Images

Entire legends have grown up around the peintre maudit Amedeo Modigliani, who died at the age of 35. Born into a Jewish family in Italy, he moved to Paris in 1906. There he soon belonged to the circle of bohemian artists, but not to any of the schools that dominated art life – neither Cubism nor Futurism. Wasn’t his short and self-destructive life also a form of protest against the prevailing conventions? He could easily have become the most sought-after portraitist in Parisian society, but he spent days and nights drawing in his miserable quarters in the Montmartre district of Paris or in the Café Rotonde, using young people, friends, girls, artists and collectors as models. He painted only a few landscapes and probably no still lifes at all. The colors of his pictures, dark and heavy in the early years, became increasingly transparent and eventually reached that fascinating luminosity that, although full of tension and contrasts, always remained in the scale of uniform tones.

After the last German Modigliani retrospective was shown at the Kunsthalle Bonn in 2009, the Barberini Museum in Potsdam is now showing the artist’s work. The focus is on Modigliani’s preferred themes of portrait and female nude, while also exploring his contemporaneity with European modernism for the first time. Klimt, Schiele, Paula Modersohn-Becker, Picasso and Matisse – the works of all these artists show connections to Modigliani’s work.

The only solo exhibition that Modigliani had during his lifetime – in 1917 at Berthe Weill’s gallery in Paris – became a scandal. Some nudes with visible pubic hair had to be removed as a violation of modesty. But the motifs were by no means clumsy – the artist brought the shape of the female body into the picture in a sensual and chaste manner. The almost transparent faces, the almond-shaped or rather empty slit-like eyes, the intentional disproportion between head, torso and legs, the three-dimensional conception of the figures as well as the light-filled and intense coloring characterize a sensitivity that was completely alien to most expressionists. Moved directly and shockingly close to the viewer, the nudes express a female independence and sovereignty that was still unusual at the time.

What is largely unknown is that Modigliani also worked as a sculptor for a while. The few surviving stone heads scattered everywhere and a caryatid – a female column figure – combine a wide variety of stylistic models, primarily from earlier cultures. Strict and aloof, as if from another world, the faces do not reveal their secret. Even though Modigliani gave up sculpture completely in 1914/15, it still influenced the style of his portraits from 1915 to 1920. He often left the subjects’ eyes empty, as in the sculptures. The slanted, pupilless eyes in particular – this is particularly highlighted in the Potsdam show – direct their gaze inwards and outwards at the same time. This creates a restrained melancholy and distance, which stands in strange contrast to the rich means of expression that Modigliani used for the psychology of his characters.

The artist placed his figures not in an objective but rather a spiritual space. He sought to determine the character of the model through the precision of the body contour, the rhythm of the lines and colors. So he basically invented a new language with each portrait. Just compare the portrait of the painter friend Chaim Soutine, an awkward, sullen-looking young man (1916), with the dandy-like, cubist portrait of the writer Jean Cocteau (1917) or the portrait of Diego Riviera (1914), in which swirling spirals the Mexican painter’s enormous body masses emerge. In contrast, the images of his partner Jeanne Hébuterne, who passed away one day after his death, are built on discreet, reserved harmonies. The portraits, which are sometimes sharpened to the point of deformation, are then juxtaposed with simple portraits of children characterized by existential insecurity.

Modigliani in Potsdam should be seen as a “chronicler of a strengthening female self-confidence,” who portrayed emancipated women with short hairstyles and men’s clothing. Early on he had grasped the new female image of the Garçonne, the tomboyish woman, which only became dominant in the New Objectivity of the 1920s.

How can we explain this strange contrast in which the discipline and sovereignty of his artistic work contrasts with the restlessness and self-destruction of his life? There will probably never be a definitive answer to this. Perhaps Modigliani had to live such a life in order to acquire the highest degree of individual freedom and artistic independence. Otherwise he might not have succeeded in creating these portraits of inner truth, human dignity, spiritualized beauty and wistful cheerfulness.

»Modigliani. Modern Looks”, until August 18th, Museum Barberini, Potsdam.

Become a member of the nd.Genossenschaft!

Since January 1, 2022, the »nd« will be published as an independent left-wing newspaper owned by the staff and readers. Be there and support media diversity and visible left-wing positions as a cooperative member. Fill out the membership form now.

More information on www.dasnd.de/genossenschaft

demo slot x500 judi bola online sbobet sbobet